On the 21st of September 2018, Neal Hovelmeier, a deputy head at St. John’s College, an exclusive all-boys’ high school in Harare, hastily came out as gay to his students at an assembly. This information was relayed in a letter sent to parents on the same day, which explained that “he is a man of complete integrity” and his “record . . . is unimpeachable.” It was later revealed that the Daily News, once the only independent paper to challenge Robert Mugabe’s rule, had been planning on outing Hovelmeier after receiving a tip from an anonymous source. Hovelmeier came out to preempt the paper’s story.

Parents staged a revolt. At a parent teacher association meeting held a few days later, many demanded that Hovelmeier resign, along with the school leadership that condoned his action. Many of the parents testified that they had chosen St. John’s because it adhered to Christian values. A few days later, citing death threats and the overwhelming parent backlash, Hovelmeier resigned from his position after working at the school for 15 years.

I was interested in the not-so-silent working of race in this story. Zimbabwe’s private schools are enduring colonial institutions. A school’s status is based on its racial makeup. Private schools often recruit white headmasters from the UK and South Africa, bypassing qualified black educators. Also, the higher the percentage of white students, the more prestigious the school. You don’t start a conversation with a well-connected person without: “And where did you go to high school?” Products of this system are often shocked to find that they, alleged “born-frees” (people born after the end of colonialism), received a quintessentially colonial education.

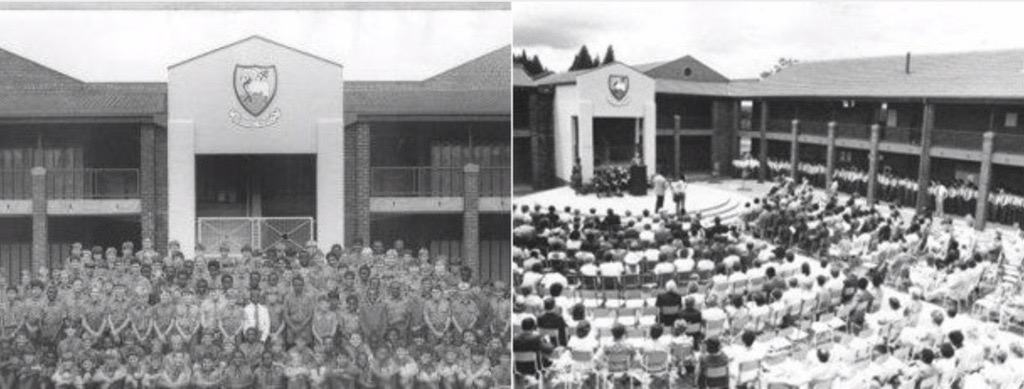

The racial politics of education were openly acknowledged in the early days of independence, when white private schools were frequent targets of a government still committed to the project of decolonization. When the black majority came into power in 1980, the survival strategy of global whiteness—fleeing when its spaces are penetrated by blackness—kicked in. Plans to establish St. John’s College took shape in 1981, just one year into independence. In 1986, St. John’s College was formally established, so hastily assembled that the first 180 students enrolled in what was “literally” a maize patch.

Ideas about who belongs where cling stubbornly to spaces, like odors on thrifted clothes, reminding us that we are playing dress-up in someone else’s possessions. In middle-class living rooms in Harare, it is not uncommon to hear private schools being evaluated according to the size of their white populations. Formerly majority-white schools that have “blackened” in the post-crisis years are held in lower esteem than those that have been able to hold their white students. Rural schools, permanently stained with blackness, are a punch line.

St. John’s is among the institutions that have preserved their racial positioning, maintaining a veneer of white exclusivity even as increasing numbers of black students have enrolled. In 1998, the state newspaper, The Herald, objected to St. John’s’ hiring of a new white headmaster from South Africa, explaining, “This new form of racism is a lot more subtle than the old fashioned kind, but is just as dangerous for the minority groups and for the nation.”

Beyond simply transmitting Western values, schools prepare their elite students to reproduce race and class status, and that reproduction hinges on the implicitly heterosexual bodies of school leadership.

The white headmaster is an important figurehead. His bodily presence signals that what is to be reproduced—knowledge, taste, and discipline—will be transmitted by a qualified representative of Western culture. As every Zimbabwean knows, you do not pass an object to someone using the wrong hand.

The deputy headmaster is all this and more—the companion to students, the good cop, the one who not only executes, but softens official power. He can be an accomplice to boyish pranks and a confidant, a guide through the turmoil of the teenage years. At St. John’s, Hovelmeier was affectionately known as “Mr. Hov” and taught drama and tennis. On Twitter, a St. John’s student posted a picture of the time his class “put a live chicken in [Hovelmeier’s] office and nobody received any punishment for it.”

Neal Hovelmeier’s body—and the aberrant sexuality now projected onto it—troubles not only the transmission of knowledge from teacher to pupil, but the intimacy required of a deputy. While the vocal majority of black parents might want St. John’s to reproduce certain Western values in its students, homosexuality, imagined to be something foreign to the nation, is not one of them. As one parent complained, “We become worried that our children will be recruited.” Others insisted that they did not object to Hovelmeier’s sexuality per se, but to his decision to come out to his students at an assembly. This was an unacceptable abuse of his in loco parentis standing, an attempt to impose his own lax values onto unsuspecting minors. This perspective was summed up in a terse tweet that someone fired off to me when I tweeted disapprovingly about the parents’ response: “He should practice homosexuality in his house!”

Disguising plain homophobia by turning it into a quibble about space and decorum—you can do it but just not where we can see it—is the bigot’s favorite trick. It is aided by the fact that the sanctity of a man’s home, and what is permissible in it, is woven into Zimbabwean cultural discourses. A Shona proverb says “chakapfukidza dzimba matenga”—every house is covered by a roof. It tells us about the opacity of domestic life, about the violations that take place right under our noses. If the violence of patriarchy can be sanctioned by the privacy of the home, this reformed, polite homophobia imagines that “deviant” sexuality should also be enjoyed secretly, away from public view.

In the videos I saw, I couldn’t help but notice that it was black and white men who got up to yell in each other’s faces, at one point almost getting into a fistfight. It made clear that what remains unquestioned in all this fuss, and what Hovelmeier claimed he wanted to combat by coming out, is the toxic masculinity—the bullying, the sexual humiliation, the targeting of weaker boys—that is part of the culture at all-male institutions. But of course, the ability to assert power over others at all costs is valued in men. It is the lesson worth paying for.

In his resignation letter, Hovelmeier insisted that he is “an intensely private person.” For that reason, he asked “for the peace to move in my life in a manner which is free from persecution and is fair for all citizens.” This coming out that resulted in a dignified retreat back into the privacy of the home reminded me of the case of two young black men who were arrested in 2011 for sodomy in Mbare, what used to be the old black township in Rhodesia. They were arrested when a roommate claimed he heard them having sex in a one-room flat that had been divided in two by a thin sheet. For them, the intimate space of the home did not guarantee protection. After their story became public news, the ZANU PF youths who effectively run Mbare hounded the two and their lawyers, accusing them of being “unpatriotic.” Under such conditions, their lawyers appealed to the court to move the case to another jurisdiction, arguing that their clients would not be able to receive a fair trial. The case has been suspended since then.

That was in the old Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe’s paranoid regime that cultivated reactionary violence because it had nothing else to offer its citizens. Mugabe—the great annihilator of all our hopes and dreams—is finally gone, but the structures that made him possible are, in a cruel twist, even more enlivened and punishing. While many can’t see themselves ever leaving Zimbabwe—who can leave a place whose rhythms, however disjointed, they know by heart?—they want their children to have a little bit more security, to be subject to fewer of the whims of a reckless state. So even as parents insist that their children must not be exposed to “unAfrican” values, elite students are being trained for lives outside of Zimbabwe. There is no expectation that those who receive educations at such schools will make their lives in a country where 90 percent of people lack formal employment and where there are few opportunities to establish the good middle-class life that a private school education ought to guarantee. (In 1998, the Herald criticized St. John’s for producing “export quality” students.)

When you leave home as a student, entrusted with parental hopes to make something of yourself, you are a bit of a stranger when you come back. What you return with—children with Western manners, an accent tinged with different r’s, unacceptable decadence—maps your distance from your parents. On one of my first visits back home during college, my older brother and I sat in the office of my sekuru, my great-uncle, as he marveled at how neither I nor my brother had any crazy tattoos or piercings even after being away from home for so long. My father smiled at such praise; thanks to solid parenting, we had escaped contamination. High on parental approval, I have always taken a special pleasure in my ability to, upon landing in Zimbabwe, immediately revert to a dutiful daughter, never truly betraying how far I have strayed. A few months ago, I lay on my back and impetuously got the word FREEDOM tattooed on my upper wrist as something of a reminder to myself about the kind of life I want to live. A few days later I thought, “Damn, no more wearing short sleeves around sekuru.”

Our parents are not stupid. I know they carry all these thoughts in their heads, measuring the risk of us going and returning unrecognizable to them versus staying and having our futures chewed up by a government that feasts on the young. They must also know that even in their homes, we are strangers to them, which is why they discipline and lecture, hoping that something will stick. But the future, which seems invitingly open out there, is also out of their control. And that’s the fear I saw in those St. John’s parents, who will in a few years, be sending off their boys to the UK, South Africa, Australia, anywhere but here. It’s not as if there aren’t already any gay boys at St. John’s who tell the lies they must tell to survive or have secret thrills. But for the parents, Hovelmeier coming out brought homosexuality into their house, hastening something that they thought they could hold off for a few years, when they could blame it on whatever bad stuff is out there in the West. That was his real transgression, his real abuse of power; running ahead of their time.

Of course, there are many who never leave, for whom the future is not out there somewhere, but at home. There is no waiting for an imagined reprieve, just a carving out of spaces where they can be.

Rudo Mudiwa