A tweet goes viral. A march becomes an uprising in two, three, many cities. A stray thought is suddenly on everybody’s mind. How does this come to happen? The question arises no less for the marketing guru than the revolutionist. If we knew how to make it happen, everybody would have 27 million followers on Instagram, or we would be in the middle of the rev, or both. But no one really knows.

That said, the vertiginous takeoff of the anti-gun movement led by the students from Parkland, Florida, is not entirely mysterious. On Valentine’s Day, the brutal and brutally familiar shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School killed 17 and injured 17 more. A mere 38 days later, the March for Our Lives rolled through hundreds of cities across the nation; the march in Washington, DC, was estimated to be the largest protest in its history. This was generalization with a vengeance.

One suspects that the greatest single factor enabling this leap from murder to movement is exhaustion—not of the participants but of whatever blockage has stood in the way of such scaled-up action to this point. The vast river of anguish and moral revulsion regarding the current configuration of gun culture in the United States has gathered force with each similar event; now, finally, it could not be held back by idiot NRA campaigns, bang-bang libertarianism, and the generic apathy or political nihilism that always looms. And the dam gave way, and almost a million people flooded into the capital.

This all is true but it offers only a pseudo-explanation. It doesn’t tell us why the dam crumbled then, rather than with the previous or next mass shooting. For that we must look to something like the specifics of the episode, the character of the living and the dead. It is easy to admire the readiness of the surviving students to speak for themselves rather than be co-opted by some interest group’s prefab campaign. It is easy to admire their unhesitating politicization, their ability to draw on the moment’s intolerability rather than abide by some bogus notion of respect that mandates a waiting period before responding. Their weaponization of youth itself, of its moral demand on the cynical olds, was as ruthless as it needed to be. There was something moving in the patience and even virtuosity with which they shrugged off the demobilizing strategies that have consistently fractured movements led by adults of supposedly greater sophistication—something moving in the extraordinary composure and charisma of the youths themselves.

Also: they were pretty white.

This is not universally true, exactly. Not all of the dead. And not quite all of the living who came to represent the movement: Emma Gonzáles, the movement’s most visible spokesperson, is the child of wealthy refugees from Castro’s Cuba. For some she is white-passing, and for many others she is an exception that underscores the more general condition, an inhabitant of bourgeois power that is in the United States irrevocably entangled with whiteness. It is similar to the idea that police officers, regardless of skin color, are structurally white: they hold a job whose basic functions include the production and preservation of differential citizenship and racial hierarchies. To put it in in less academic terms, the police, whatever their backgrounds, are charged with making sure that some lives matter more than others. It is for this reason that Black Lives Matter is both a general demand and, necessarily, a specifically anti-police movement. And therein hangs a tale.

At just around the moment of the March for Our Lives, the racial character of the movement became the occasion for serious critical reflection, distinct from the bleating of a million NRAholes and Second Amendment enthusiasts. The “Parkland kids” were set against BLM in an intuitively plausible comparison of two dynamic movements driven by specific episodes of murder, and by the national and institutional relation to gun violence. And the criticism went like this: the relative celebration of one movement—the lionization of the leaders, the magazine covers, the verified Twitter accounts, the way that Facebook seemed to become for a month a planetary project about Parkland—could be explained only by simple racism.

I think this is inarguable. But I want to stay with the way this happened. To think that political identifications operate as directly as “I like this because it’s white and dislike that because it’s black” is to miss much of how race and racism operate at a practical and daily level. And in turn, to miss this practical dimension is to ignore how political management of populations works. Because most of all, the wildly asymmetrical response to the two movements is a story about social discipline. It is a story about the soft power of social sanction being used to remake hard limits about what will be tolerated and what will not—to channel all social conflict into a very narrow performance. Even as this particular gun control movement was lifted on high, rebar was being loaded into the fresh concrete setting at the edges of the political arena where all of us dwell. It was a trap.

If you show up with a petition in hand, some cop is gonna say they thought it was a gun.

In the first instance, the practical difference between the movements was one of tactics. Because BLM is not a single organization, any statement of “BLM does this” or “BLM wants that” is bound to get it wrong. Still, it is inarguable that BLM is associated with moments of extraordinary and occasionally extralegal militancy. For every swerve toward conservative policy intervention like the fantasia of kinder, gentler cops animating Campaign Zero, there are the rebellions in Ferguson and Baltimore, in Milwaukee and Charlotte, and the hundreds of other places vibrating sympathetically with the fury of communities grieving the police murders of their people. These rebellions are characterized most evidently by a refusal of the call to order, a refusal of any respect for those who hold the law in one hand and their blood-spattered service-issue .40-caliber Sig Sauer in the other. They take the streets. They take the shops. They take the freeways. Fire back at cops. I suspect that if the Parkland kids had come out on February 15th smashing windows and shouting “Fuck the Police,” things would have gone quite differently. The repression they would have faced might not have been quite as militarized as the state response in Ferguson—but had they heaved molotovs, there would have been no love fest premised on their whiteness within the nation of sensitive centrists.

This is not to argue that the response was thus somehow race blind; far from it and by the way “race blind” isn’t a thing. Rather it is to raise the question of why one struggle is more likely to fight in the streets while the other rides the rails of political legitimacy. The answer to this question is not opaque. It is already present in the names: Black Lives Matter and March for Our Lives. As suggested above, the former insists that there is a structural inequality already embedded in the category of the legal, in the purported equality of the state, that the law is thus unfit to address. The latter . . . well, look at it. The name, its idea, is perilously close to All Lives Matter. Only one of those positions can make claims on a sort of liberal universalism. It is, no surprise, the one without “Black” in its slogan.

It is not so hard to imagine that, among those who begin from empowered bourgeois experience, mostly if not entirely racialized, it is possible to imagine achieving legal redress via petitioning the government in good faith. They recognize themselves in the courts, the opinion columns, the legislature, the most basic organization of the world around them (it is hard to overlook movement spokesperson David Hogg’s tweet from June of this year: “I love capitalism”). If one begins instead from the experience of the black proletariat of Ferguson or Baltimore, the absence of such possibilities is a baseline. There is no such self-recognition. They do not find an honest reckoning with their lives and their dispossession in any of these places. And this absence is knotted up with ceaseless experience of the state as intractably violent. If you show up with a petition in hand, some cop is gonna say they thought it was a gun.

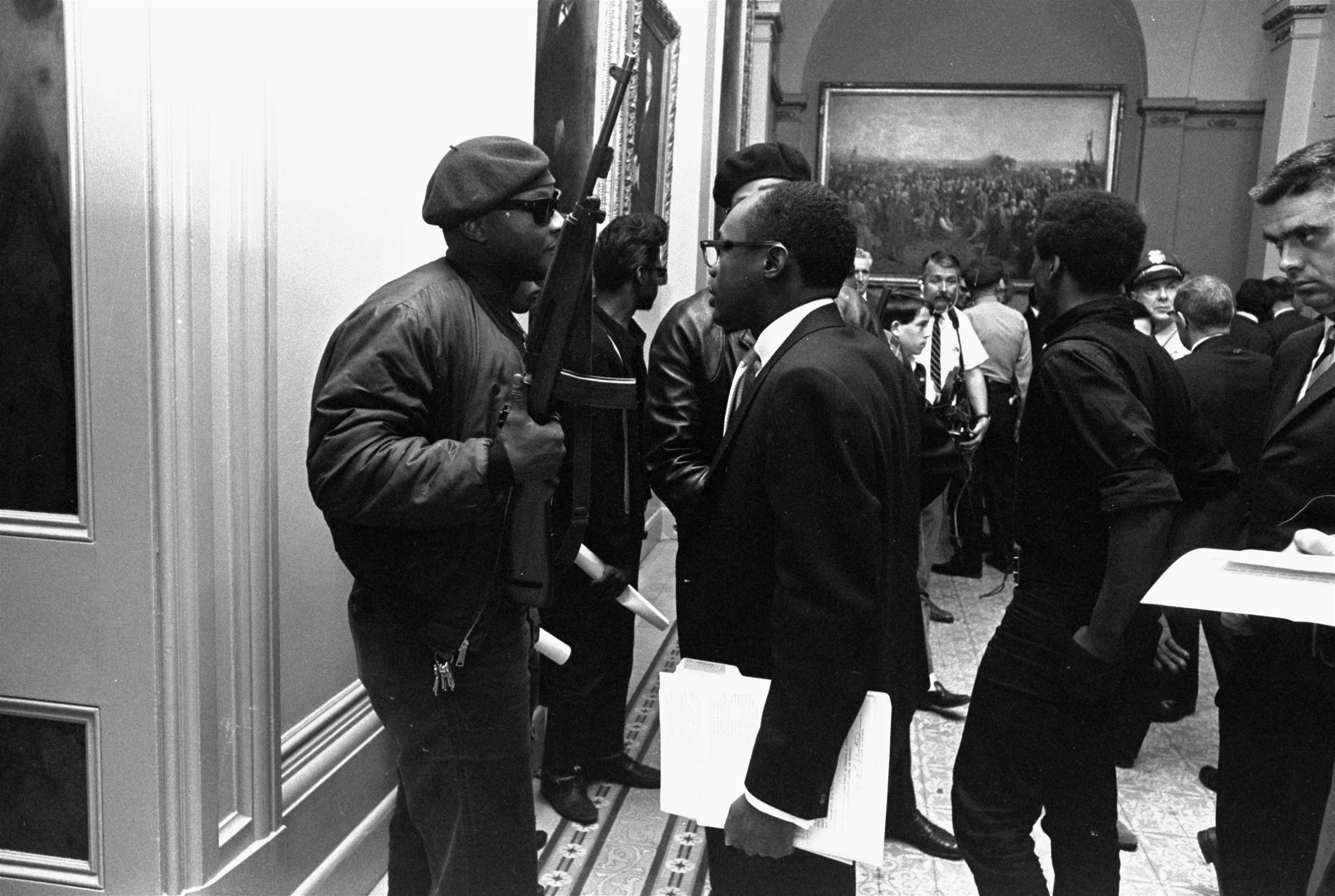

This distinction is not absolute. Certainly there are adherents of respectability politics in every substantial social movement, and likely some street fighters too. Moreover, the simplification down to black and white, not this essay’s but in the discourse, obscures a great number of political positions, even if we are just discussing race and ethnicity. Shit is complex. Nonetheless, the division is real; it has a history. In many ways it recapitulates the turn to Black Power in the late sixties, born in part from a sense that a politics premised on moral appeal had reached its limits in the struggle for equality and true emancipation (“that whole thing,” Malcolm X said 54 years ago, “about appealing to the moral conscience of America—America’s conscience is bankrupt”). It is no surprise, recalling that period, that debates over gun control are always discussions about race and policing: our current firearms regime comes down in large part from the 1967 Mulford Act in California, which inspired numerous laws nationally. It was enacted to stop the community patrols against police violence conducted by the Black Panthers and has been applied unequally ever since. Given our image of the classic NRA member, a caricature but not a baseless one, it is easy to neglect this salient fact: gun laws always criminalize black people first.

Our memory of that passage in time is often reduced to the iconic, overburdened image of Panthers at the State Capitol in Sacramento, berets aslant, rifles out. But this image is not about guns. It is an image of an entire approach to social transformation, in which the state monopoly on violence, deployed ceaselessly to subordinate much of the population, is a problem rather than a solution. Without revisiting the exhausting debate as to whether or not this approach was productive, we can still say that, for very good historical reasons, there is a racialized divergence regarding the great question of how to proceed politically. The gap between the two positions widens and narrows and widens again, persisting into our present. The militants of BLM and the media-ready spokespeople of March for Our Lives set forth the basic polarity.

And finally, I think, this leads us to the most explanatory account of this moment, and of the startling if still incomplete success of the white gun control movement. The massive love rendered to the Parkland kids—the social sanction meted out by the media, by those who joined the marches, by Twitter likes and supportive pols—has a singular function: to legitimate and valorize one particular mode of politics while banishing all the others. This need not be a conscious strategy of some powerful person or persons for it to describe the systematic project of power itself. It is an ongoing and generalized enforcement of the idea that you can have a popular movement only if you concede from the beginning that you will basically follow the choreography preferred by the very forces you are seeking to change.

And this disciplining of social movements does not come only from conservatives, reactionaries; does not come only from the side intent on (for example) making it legal to run over protestors if they block a road. One can witness it inflecting left discourse. Consider as an exemplary case this essay by L. A. Kauffman in progressive venue the Guardian, “We are living through a golden age of protest.” Surveying recent political antagonisms, it arrives at a sympathetic and vital conclusion: that for all the scope of contemporary actions, they will need greater militancy to achieve their goals. No doubt. And yet, what seems to be a broad survey features some striking blind spots. There is a lot of counting. The article reels off the protest data for the Trump era, not neglecting to linger on March for Our Lives, compared in scale favorably to protests against the Vietnam and Iraq wars. It is not compared to Black Lives Matter, which does not appear. Neither does Ferguson, the most sustained antistate struggle of our era. Neither do any of the last year’s antifascist actions against white nationalists, nor the street protests at the inauguration, nor those activists flouting immigration laws to aid refugees. These activities, and the mode of politics they offer, go unmentioned and unnumbered. They don’t count. Meanwhile, the one gesture toward the politics of racial oppression celebrates the reprise of the sixties’ Poor People’s Campaign, an explicit return to a by-now-consecrated version of Civil Rights protest prior to Black Power. In its inclusions and omissions, the essay risks the paradoxical effect of affirming the conservative model of what politics can be recognized and what cannot.

I would argue, finally, that this is what the Parkland moment is about, more than gun control. It is about making absolutely clear that there is a right way to do politics. This way will be rewarded and admired. This way counts, and has a race and a class to which it appeals. If you feel included by that, you are celebrated over here. You are seen. You have a right to the very category of politics. If you do not believe that this particular approach and appeal will serve, you matter less. Maybe not at all. You are left over there, on the other side of the reinforced concrete, excluded from the political arena altogether, just as you have already been excluded from so much else.