In August, I secured a five-year visa to China and I felt immensely grateful. I’ve had eight visas to China in less than three years, and this would give me a half-decade’s reprieve from the finicky tedium of the applications. It was also proof that I was finally Chinese enough… for something.

I was born in Shanghai, but I moved to Melbourne with my family as a kid; since the Chinese government doesn’t recognize dual nationality, I automatically surrendered my citizenship when we became Australian citizens. I was eight years old. Over the next twenty-five years, applying for visas to China has been a familiar ordeal. We visited our extended family in Shanghai nearly every year, but every application seemed to introduce a new requirement, a new twist to the red tape, a process which seemed particularly callous when my grandfather died. I sat at the visa centre on St Kilda Road all day, shuddering with tears as I waited to hear if I would get an expedited visa to attend his funeral.

(A clerk told me she could only fast-track my application if I had a copy of his death certificate; I managed to get my aunt to send a photograph over the WeChat app).

At worst, the process was only a minor inconvenience. It might have taken several trips to the visa office, but unlike our relatives in China, we would always be permitted to travel, in the end. According to the Henley Passport Index—which compares travel freedom for different nationalities—in 2018, an Australian passport confers visa-free access to 183 destinations, compared to 74 destinations for a Chinese passport. That’s not even taking into account the travel restrictions that Chinese nationals may face from their own government; recently, Radio Free Asia reported that a Uyghur philanthropist and father of four was sentenced to death for taking an unapproved hajj, rather than a state-sanctioned group pilgrimage.

The privilege of Australian citizenship is obvious, but it also highlighted my sense of dissonance. The more I travelled, and the more ludicrous it seemed. I’d been to Thailand, Morocco, Kyrgyzstan, and Spain without a visa, without speaking the language, without knowing a soul. But I needed permission to spend a few days in the city where I had been born and where my grandparents were buried.

I was thrilled when I first heard, in February, that the Chinese government would be offering a five-year multiple entry residency permit for foreigners of Chinese descent. But the thrill was not only the prospect of avoiding a recurring administrative nuisance; it was the promise of recognition for people like me. According to the ministry, the new policy specifically aimed to attract skilled overseas Chinese to take part in the country’s economic and social development. We’ve been transformed and redeemed, I thought; no longer wayward traitors, we would now be the long-awaited, always-welcome prodigal sons.

At that point, I’d already spent two years living in Shanghai, where I was working for an English-language media outlet called Sixth Tone. But I felt like I would never really settle in. Every work permit had a maximum validity of 12 months, and each year the rules around them were becoming stricter. I’d moved to Shanghai to be near my grandmother and to improve my Chinese, but as it turned out, my hectic work schedule left me little time for anything but work. But working less wasn’t an option, since my visa would be cancelled if I quit my job and even changing employers was a hassle.

The five-year residency permit seemed like an opportunity for breathing space, an opportunity to better balance work, family, and my own writing. The media reported that the visa was not to be restricted to a single purpose; applicants were to be able to work, study, visit their relatives, conduct business or cultural exchanges, and deal with any personal matters in China; anyone with at least one Chinese ancestor was supposed to be eligible.

Alright, I thought; bringing diaspora back. I’m into that.

The reality, I soon discovered, was not so simple. The visa was still divided into categories: my employer would have to sponsor me if I wanted to keep working, but if I applied for the “family reunion” category, I wouldn’t be able to work. The only benefit over a regular work visa, it turned out, was if I wanted to stay with the same company for five years, which I didn’t.

Nevertheless, after I quit my job in August, I decided to apply for the five-year residency permit under the family reunion category, to be near my grandmother. Immediately, I was on the clock: applications had to be submitted to an Exit-Entry Administration in mainland China, so I had less than a month to get it before my 30-day bridging visa—misleadingly called a “humanitarian visa”—expired. All I had to do was prove who I was, but this was easier said than done: when I was born, in the 1980s, China didn’t issue birth certificates nor any personal identification showing who your grandparents were. The only document I’d received at birth was a tiny pink stub from the hospital that stated my sex, weight, and blood type, with no name.

I visited the district police station near my grandmother’s Shanghai home to see if they might hold historical records. The dimly lit station was deserted: everyone was out the back having dinner. After I’d waited half an hour for them to finish their meal, a young male officer ambled in with an off-hand apology. Eventually, he managed to locate a weathered old hukou ben—household registration booklet—which included my name, and certified that I had lived at that address with the primary householder—my late grandfather—and his wife. (Technically, my grandfather’s wife would not necessarily be my grandmother, but they didn’t quibble.)

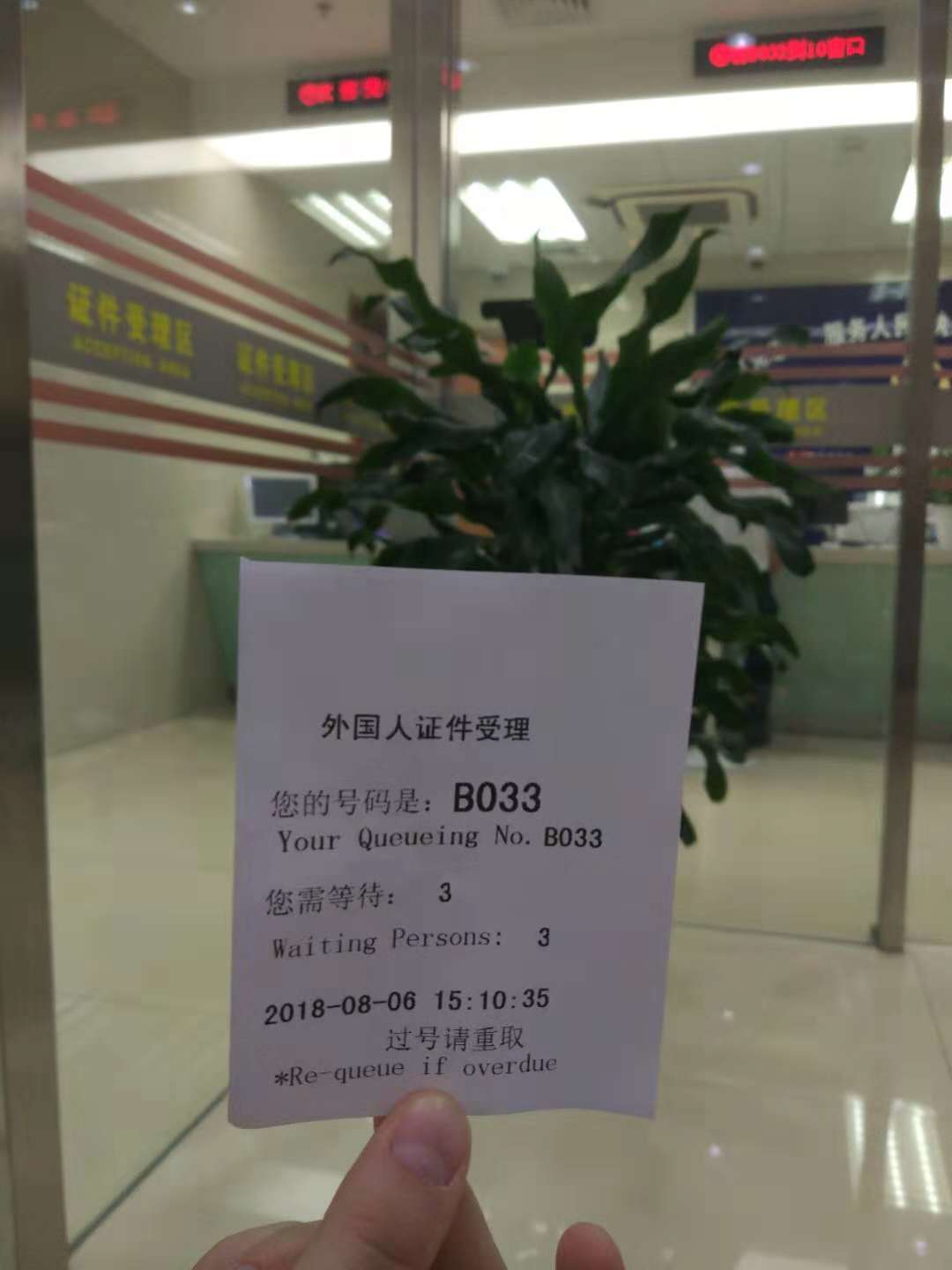

The next stop was the Exit-Entry Administration. The cramped district office was housed in an old office block. Anxious, confused foreigners filled one corner—many accompanied by HR personnel or visa agents—while the rest of the plastic chairs were occupied by Chinese citizens applying for passports or travel permits to Taiwan, Macau, and Hong Kong.

Interactions with Chinese bureaucracy involve a lot of code-switching. I often play the part of the guileless, bumbling foreigner—punctuating my broken Mandarin with excessive xiexies—but this time I had to pass as a long-lost Shanghai native. Luckily, my Shanghainese is more fluent than my Mandarin and I’m not above exploiting provincial chauvinism to get something done; I quipped with the clerk that our parents must have had the same idea because he and I had the same character in our names. I pulled out a bulging folder of paperwork: the police officer’s statement, originals of my grandmother’s hukou ben and ID card (and a handwritten letter of invitation from her), a copy of my Australian citizenship certificate stamped by the Australian consulate in Shanghai, and an official health check report.

I was lucky; because I was born in China, because I had a living ancestor who was a Chinese citizen, and because my family has remained in central Shanghai for over 60 years, it was easy to access official records of my brief life in the country. My Australia-born sister might not be as successful, let alone my partner whose mother left Hong Kong as a child. I have heard that applicants can be rejected if they have only been to China for short holidays, and I suspect that non-Han applicants—especially from ethnic groups associated with political dissent—would have a very different experience than mine.

There is no official information online about how to apply for the five-year residency permit, what it entitles you to, and who is eligible. I’d guess that someone pitched the visa as a strategy to lure back émigrés, to reverse China’s brain drain, but that implementation muddied the initial vision into something unrecognizable. This isn’t unusual. The Chinese state might seem like a totalitarian machine from the West, but up close, it can look a lot more like a beleaguered octopus, disparate limbs flailing. Most of what I’d seen in the media about the five-year residency permit turned out to be untrue, even when based on explicit statements from the ministry.

One particular aspect bothered me: I’d hoped to get a residency permit because of my ancestry; rather than being invited by a relative or employer, I’d hoped my own Chinese-ish identity would be enough, a sort of dual citizenship lite. But that simply wasn’t the case. My application was entirely dependent on my grandmother’s invitation. I was still a guest in my homeland.

Two weeks after submitting the application, I joined an impatient crowd outside the main Exit-Entry Administration office, a huge glass and chrome building in Pudong District about an hour from my flat via the metro. It was 8:30am and already 30 degrees. After visiting this office a dozen times over the last couple of years, I felt equipped to field queries from other applicants. “Why is there a ‘service paused’ sign?” a man mumbled to his wife. “They’re not open yet,” I piped up. “The doors open at 8:45am but the counter opens at 9:00am.”

By 9:03am, I was walking out the door with my passport in hand. I snapped a photo of the five-year visa page and sent it to my mother and a few friends. A few hours later, I was at Hongqiao Train Station, embarking on a six-week trip through China and Central Asia.

As I traveled through Xinjiang—the far western frontier of China where Uyghurs and other ethnic minority Muslims are being detained in “re-education” camps in staggering numbers—I worried whether police would notice the family reunion visa whenever I was stopped and had to show my passport. If I got into trouble, would it implicate my grandmother? Now that I’m back in Australia, I still feel pangs of anxiety if I so much as tweet about the situation in Xinjiang: I have more freedom to speak on the issue than Chinese citizens, and much less to fear than Uyghurs anywhere, but I still dread the possibility of having my visa cancelled and never seeing my grandmother again.

If China offered dual citizenship, I wouldn’t apply. Chinese authorities tend to show more restraint when dealing with foreigners than with citizens—though recently they have blocked two U.S. citizens from leaving the country because their father is wanted for fraud. Australia is part of the problem, too: Here, Chinese-ish people are regularly vilified as pawns of the Chinese Communist Party (regardless of their individual political positions) and right-wingers call for non-white immigrants to be deported, regardless of their citizenship status. In 2017, for example, parliamentarian George Christensen called for the “self-deportation” of engineer and media personality Yassmin Abdel-Magied after she tweeted what is actually a fairly mainstream opinion; freedom of speech for a Sudanese-Australian like her, it turns out, has its limits. Being nothing other than Australian is the best way to protect myself, on both sides.

Jinghua Qian