If you went to the Oakland Zoo ten years ago, you could see a “Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling.” I never did, but in 2009 a friend sent me a picture of it, and I was properly startled; I wrote a blog post about it, and I even emailed the Zoo director to ask—in maximally polite and “just inquiring” tones, in a careful someone-else-might-misunderstand-but-I just-want-to-understand-ese—why in the earthly fuck there is a hut for persons in a goddamn zoo.

And he emailed back! It was a polite account of the design process, equal parts rational and bat-shit, that he had clearly given before. The problem, he said, was that zoos tend to show animals separate from each other and from the rest of the world, but because Africa “is a total environment”—something he knew from having visited many times—they wanted to give “a sense of unity in the East African experience…to give our visitors an insight into the beauty of the outside world; in this case, the world where our African animals live, and people coexist.”

And so: a “Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling”—rendered in anthropological detail—next to a similar hut where you could buy ice-cream. Because that makes perfect sense; Africa, as you know, is a total environment.

I was busy writing a dissertation about big game hunting in East Africa and the Americanism of settler colonialism, so I never went; who has time to visit a zoo? I don’t even remember if I replied to his reply. What was there to say to a person who finds such a thing normal, even commendable? Who so thoroughly lacks the frame of reference that your impulse to write him implies, that it exhausts you to even think about how to explain it? I was defeated by that conversation.

I wrote a blog post instead, because I knew that that would be easy; the people reading it would understand my perspective—because back in those days we wrote angry blog posts about things. If anyone from the zoo ever saw what I wrote, I never heard about it. I also never called it to their attention.

The hut is still there, but the signs are gone.

When it was built, a lot of thought went into the building, into the plan and design:

I call this the Lion King Exhibit, and it’s gonna be real nice,” said construction foreman Gary Ehlers, watching his 40-member crew laying sod and grading the paths with a backhoe.

The huts look authentic, for the design team went to the trouble and expense of importing eucalyptus poles and thatching grass from Africa. The poles are embedded in the daub-and-wattle walls, which have been stained brown to simulate cow dung, a common building material in Kenya.

“Everything but the smell,” Parrott joked.

The paths and huts and faux cow dung are all still there—everything but the smell!—but there are no signs to tell you why it’s there, or what it was designed to mean.

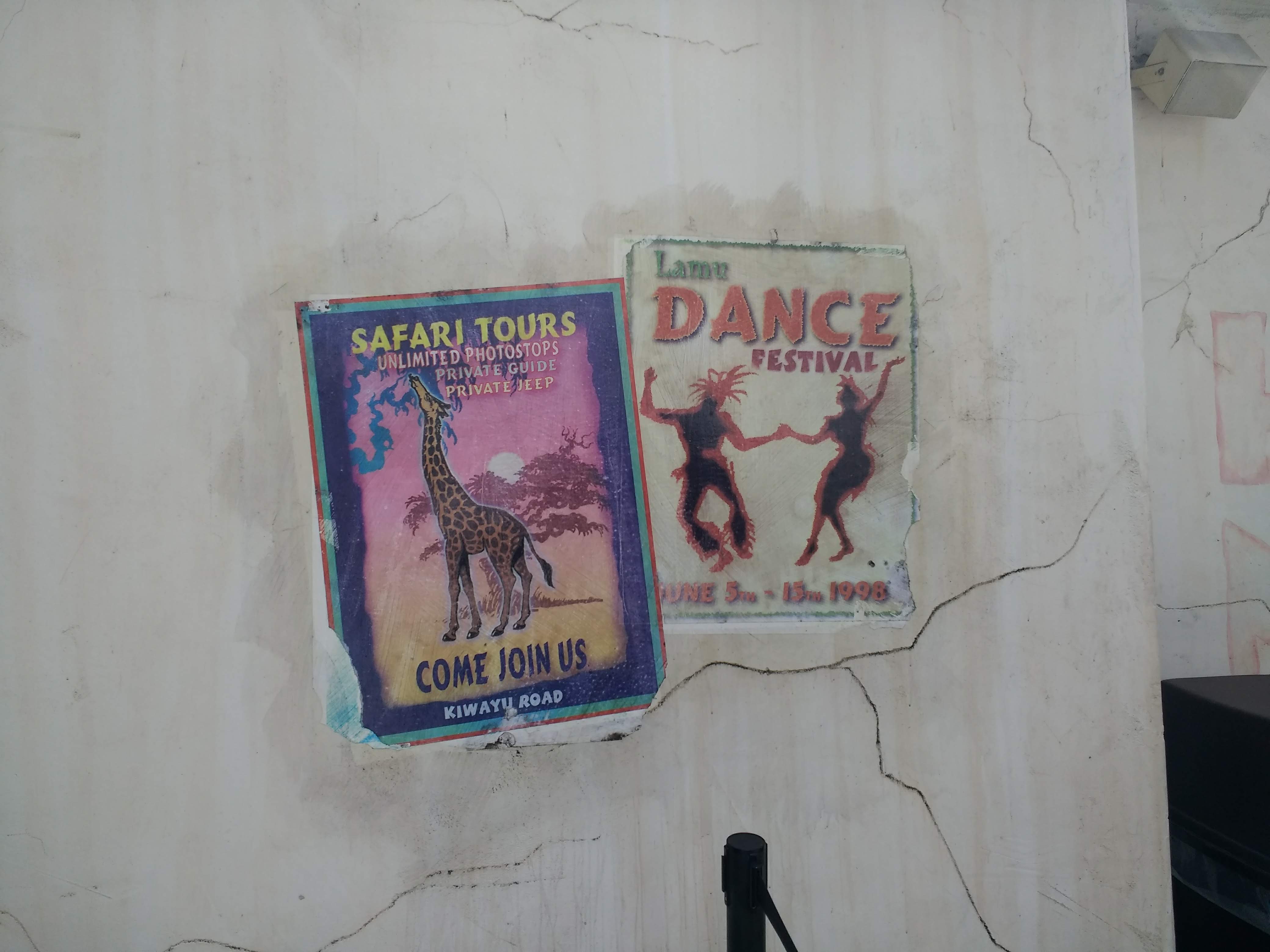

There are still kitschy safari signs at the entrance of the museum and a certain colonial-era “Kenya” is a sort of unexplained reference point throughout; there are Tusker Beer advertisements and a vintage-y sense of Swahilish East Africa tourism, to give you that good old jambo feeling.

None of that feels like part of the zoo proper; it’s near the ticket-takers, the gift shop, the snack bar.

Over where the hut is/used to be, there’s still the statue of a man and a child, called Kushika Myoyo ya Kesho (“Holding Tomorrow’s Heart”), with an inscription explaining that it’s “a tribute to the nurturing principle inherent within our fathers, brothers and sons.” But in the absence of the Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling sign, you can’t even remark on the odd apt-ness of a statue to men’s nurturing principle (but not to women’s) alongside a “Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling.”

If I hadn’t been looking for it, I wouldn’t have found it. The building that used to be the “Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling” isn’t that any more, but it’s not anything else. It’s just a little side area, next to the snakes, empty, dusty and neglected.

Maybe it’s unexplained because no one needs an explanation, or maybe because no one wants to give it; maybe it’s unexplained because of shame.

You can still find the petition campaign to get the “Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling” removed if you look for it, as I did; you can find the update explaining that the effort succeeded. In the intervening years, Black Lives Matter took off, and though Oakland’s history is its own, you can see some of the language of BLM in that petition. Or maybe I just see it there because I’m looking for an explanation; maybe a reference to “black lives” seems to explain something, because otherwise there’s nothing, and the absence of this hut seems to require a story.

And maybe it doesn’t. After all, you don’t need a hut that says “Traditional East African Woman’s Dwelling” to understand the link between safari-culture and zoos, any more than understanding why The Lion King is filled with Kiswahili requires you to read the dissertation I was writing, ten years ago.

In any case, you won’t get an explanation. No sign explaining why these huts were built this way or what the philosophy behind their construction was; what they used to be, or what they are now. It’s not mentioned on the website.

Aaron Bady