Reading the first 38 pages or so of Anna Burns’ Milkman

I stopped reading a novel I find to be extremely good (and you can quote me, I find Milkman to be an extremely good novel) to tweet about it, which led me to learn that the New York Times had a very bad review of the novel, and WOW that review of Milkman is bad. I’ve been mad about it for days.

By contrast, Milkman is good. I’d only read about 38 pages of it, but I’d already read some of them multiple times, like doubling back to look again at paintings in a museum you’ve already seen. I don’t mean that it’s some kind of Great Work of Art That Will Stand the Test of Time, you understand—and not because it isn’t, either; it won the Booker Prize, so maybe it is—but I’m also not sure I think “Art” is that thing either. Who wants immortality? I just want a decent job and a comfortable place to live, and I think that’s what art mostly wants too.

(When Anna Burns won the prize, her response was basically “sweet, I’m poor, so I can use the money.”)

Despite its harrowing subject, reading Milkman reminds me of how going into a museum and spending a few hours slowly looking at things and reacting to them—and going back to see them a few minutes later—slows down your perception of the world and calms the bees buzzing in your head. It’s like yoga for the brain.

Meditation, I guess, is what we call yoga for the brain. But I find reading this book to be an oddly meditative experience, “oddly” because it’s a novel about violence and paranoia and fear. But there it is: Milkman is a novel that slows me down, the way standing and looking at paintings in a museum slows me down; it makes me think and feel and even laugh, and the way taking a walk in a light spitty rain—where it’s just wet enough not to get you wet, just cold enough not to get you cold—makes you sort of sharpen your perceptions, that’s what this book does for me. And like meditation, where you learn how bad you are at focus and concentration by doing it, I’ve been reading this book in bits and distracted pieces, for over a week now.

Social media in no way contributes to my inability to concentrate on reading a novel, of course.

I am #StillMad about this review of Anna Burns’ Milkman

After I read that very bad no good review, I tweeted angrily about what a bad review it was, and then I left the café where I had been reading and stormed into the bookstore where I bought the book—where I used to work—and I badgered them about what a good novel it was. They were busy, but they humored me. When you work in a bookstore, it’s fun to have people who are excited about books come and badger you about them; also, since I used to work in that bookstore, they usually put up with me doing it. Brad wondered whether the reviewer who panned it was also the reviewer who panned Álvaro Enrigue’s Sudden Death, and no one could remember, but if it was him, what a scoundrel. Fuck him, it was generally agreed. No one else had read it, but Julie was “reading” the audiobook, which struck me as an excellent way to experience this novel.

I did not tell them that I’d only read 38 pages of it, but I freely confess it to you, now, as there shall be no secrets between us. And I also confess that I do have some residual uneasiness about proclaiming the worth of a book I’ve not finished, even now. But intellectually, I’m fine with it, and this is why: I’m right. This is a very good book. Sometimes 38 pages are enough to tell.

And of course, not finishing a novel does not, in practice, preclude a bookseller from declaring a book’s greatness, for reasons that have everything to do with what a bookseller’s world is shaped like. Booksellers struggle hopelessly with the number of books there are to review, the sheer vastness and never-ending velocity of publishing’s flow; you do the best you can, but ultimately, you just can’t. So you make do. You dip into books here and there to get a sense of it–and you get good at working off of those little tastes–and you listen to other people’s opinions—people whose opinions you trust—and then you pass those opinions on as if they are your own.

For example, I cheerfully recommended Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow many times, describing it to would-be customers the way Pam described it to me, and I fully expect they were well-served by my recommendation; Pam’s judgement is good. And of course you read reviews. But, well, you learn to read reviews with a certain… selectivity.

I am still a great unfinisher of books. I’ve only read the opening pages of Emiliano Monge’s The Arid Sky, for example, but his sentences are incredible and you can tell he’s doing something, going somewhere, and getting something done. That I would like to read it—that I read a few pages and said to myself “This is a damn book”—well, what does it matter whether I actually did? If I was still a bookseller, I’d be as vigorously pitching it to would-be readers as I used to hawk Laia Jufresa’s Umami, a novel I read the first half of, was blown away by, and never finished.

(I am actually a little embarrassed that I didn’t finish Umami: it’s a crazy good book, but something got in the way and then it was weeks later and I picked up some other novel, and, well, I am fallen and imperfect.)

Three days later, re-reading the first chapter of Anna Burns’ Milkman

I started from the beginning again. It was one of those moments when you suddenly look up and realize days have passed and if you don’t start back into reading the novel you’re reading, you won’t be able to pick up the thread again, you’ll have forgotten not the characters’ names–even though this is a novel where no one has proper names anyway, which is part of its whole thing and it works–but you’d have forgotten the immediate context in which each event is carefully laid out.

I started trying to read the book again, but I couldn’t figure out where I’d left off, so I started reading the beginning again, and then skipping forward a bit, reading for a while, and then skipping forward, and so on. To be honest, that works as well as anything else; the book is, well, I’m tempted to call it unspoilable because its first sentence gives you a snapshot of the entire plot—it’s one of those “contains the whole of the novel in one sentence” novels—and then the first chapter also gives you an abbreviated version of the novel.

(It’s about the paranoia of living in Belfast during the troubles, amidst car bombs, hijackings, murders, and state surveillance, and about mostly being concerned with what men will do to you, and what a man who suddenly takes an interest in you—who stops his car on the street and offers you a ride, and takes no for an answer, who suddenly shows up when you’re out running and runs with you—might do if no is the answer, and how much scarier that actually can be; it’s about being eighteen years old and not knowing a lot of things, and yet the novel is also written to think about those things; it’s about what an older and wiser woman can know about what she didn’t know, yet, when she was eighteen; it’s also about how fear and tension distorts language and thought.)

I read the beginning out loud to Lili, because I think she might like it.

It’s also a pretty funny novel! I had decided that Lili might like this novel, and even though I rarely have success recommending books to her, I found the right moment and read the beginning out loud to her. When I got to passage about how the Milkman isn’t really a milkman—“He didn’t take milk orders. There was no milk about him. He didn’t ever deliver milk. Also, he didn’t drive a milk lorry”—she laughed out loud, and I suddenly had the deep critical insight that shit is funny. I’d been absorbed in the novel and hadn’t noticed.

(You already knew it was funny, she just told me, reading this. But I don’t think I did!)

I didn’t really notice the jokes the first time, I think, because when I first started reading it I hadn’t quite figured out what the novel’s whole thing was yet. It’s very funny, but in an extremely slow burn sort of way, the kind of humor that’s played so incredibly straight you wouldn’t dare laugh at it, until you stop for a minute and think about the words.

Maybe it’s easier to laugh out loud if it is read out loud, but once I figured out that the book was funny–and I’ve laughed out loud while reading it–I’ve tried and totally failed, multiple times, to explain what it was that was funny; the more I’ve tried to explain the jokes, in fact, the more I’ve beaten it to death with a shovel. Lili has endured multiple “ok, so this thing that just happened in Milkman” stories and none of them have been satisfactory to her.

The lesson here is probably that Anna Burns wrote it in a particular way and because she’s a very good writer, that’s the best way for it to be written; nothing clarifies the skill with which a joke has been told like telling it badly.

I read most of the second chapter of Anna Burns’ Milkman, which is a much longer chapter so I don’t quite finish it

I had my phone with me, but because I was waiting for Lili to finish a radio interview she was doing, and because the phone was running out of battery, and because we’d need that to coordinate, I couldn’t keep checking it. As a result, I read most of the long chapter in which her boyfriend fixes a car and gets in a fight and has a friend whose proclivity for cooking makes his masculinity suspect to all and sundry. Moreover, I read this long chapter in a dog park nearby, where I once met an internet friend in person; she had been waiting some time for me to arrive before I did, but when I did, she observed that no one will stop you from just hanging out in a dog park and petting the dogs when they come up to you, even if you didn’t bring a dog to the party. It was a lifehack.

Her wisdom held true; no one looked askance at my presence. A small terrier hopped into my lap when the other dogs were being scary, and a big golden retriever insisted on peeing on the tree I was leaning against–but politely, waiting for me to move out of the way–and so I did, to a nearby rock.

Lili laughed at me when she left her radio interview and discovered where I’d been reading. She seemed to think it was very silly of me, but honestly, it’s a public place where people bring their dogs to play, very bucolic and pastoral. Why not bring a book and read there? Where is a better place to read a book than a park with lots of dogs? It’s kind of a crime that this is not more widely recognized, but maybe people don’t want to spend their reading time wondering if this dog sniffing your pants leg is going to pee on it.

I really like the book’s exploration of masculinity.

I read a bunch more of Anna Burns’ booker prize-winning novel, Milkman

I read another chunk of the book in a café that recently re-modeled—and which is now worryingly nicer, but still pretty basic and normal—and when a woman came in with a comfort dog, and tied him to a giant pipe right next to where I was sitting, I asked her if she wanted me to move down so she could sit next to him; she indicated gruffly that she did not, and then went behind the counter and, oh, ok, she’s a barista at the café, she brings her dog there while she’s working.

(That sidetracked me for a minute: thoughts about how I’d kind of like to get Pepita classified as a comfort dog so I could bring her to stuff, mild guilt at the thought of gaming the system just because I like taking her places, wondering whether it’s better to bring the dog with you when you work or leave it at home).

After that, I read some brutal passages about how the military killed almost all the dogs in town, with this comfort dog sitting next to me. I wanted to pet him; I did not, because his harness told me not to, and I am a very good reader.

After reading some more of it, in the same café, in the same sitting, I re-read the New York Times review which makes me mad again; I flip back to an earlier part of it that suddenly made me think newly about how bad that review was.

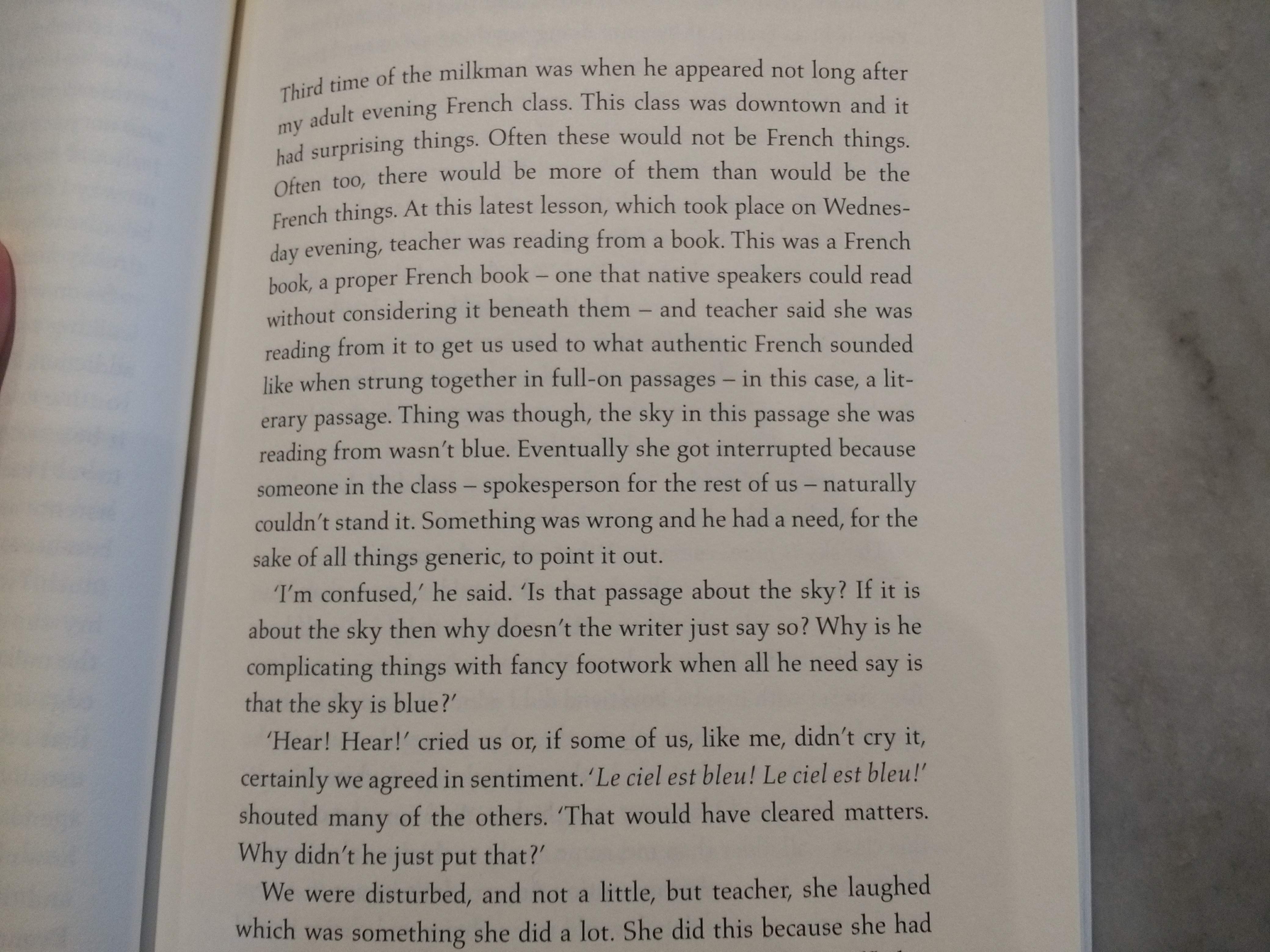

When I first read the passage in her French class, I laughed at it, as humor, but it was only a bit later that I started thinking about what a cunning burn she had cleverly written into this novel, already satirizing the New York Times review that had not yet–but predictably would be–written.

The reviewer’s main complaint is that the book makes him work too hard; “so much effort for so modest a result,” he says, and complains that the book is difficult (“willfully demanding and opaque”). Some books, he allows, can be difficult. Books with poetry can be difficult and worth the effort, books written by dead modernists of the Joyce, Eliot, Faulkner vintage. But this book has no poetry; this book is “interminable,” he says.

OK. So there’s a passage which is hard to paraphrase—and I know this, because when I tried to explain it to Lili, she was very “um, ok?” and I guess you really you have to read it—but, well, here it is. Basically when a bunch of students are reading a Fancy French Novel in their French class, they get angry because the fancy-pants author describes the sky in a variety of magnificent colors and shadings; to their way of thinking, all of the truth of a sky’s coloration is encapsulated in the phrase “the sky is blue” which, as everyone knows, is the phrase that most encapsulates the sorts of things that everyone knows, so who is this French author to come along and drag us through interminable poetry? Why is he making us work when we already know what we need to know?

It’s hilarious, but written from a place of deep empathy: the protagonist of this novel–who more or less agrees that the sky is blue–is a dumb eighteen-year old. But the book is narrated by her much older self, a narrative voice that often says things like “I didn’t realize then” or “when I was that age, I didn’t yet understand” while also trying to describe and understand and remember what it was like not to know things, yet, or to be so afraid that you couldn’t let yourself feel things, or to be so angry that you didn’t have the self-possession to really see what was happening, or to be so tense that you couldn’t notice that things were funny.

The students in that French class are all of those things, and it’s why they don’t like the book; the sky is blue, they insist. They do not understand the value of difficulty, or digression, or the kind of wild, free, and reckless elaboration that people who don’t read poetry much sometimes call “poetic”; as a result, they don’t have the time or inclination for his digressions. They get angry.

Anyway, you can read it, I think it’s good.

An interim, in which I am not making much progress in the novel, if by progress you mean advancing towards finishing the novel (but why would I want to finish this novel? I like this novel!)

We don’t run book reviews at Popula. There are lots of reasons why we don’t do that, but one of them is the “Dwight Garner” problem: what is this position of authority from which this individual–the author of the aforementioned, much-maligned NYT review–pronounces on this novel’s quality? And why would we read him as if he has it? Can you read a “book review” and not be interpellated into the person being -splained at?

Because here’s the thing: there is no such thing as a book review; why would we act like a book is something that can be reviewed?

What happened was this: Dwight Garner is employed as a book reviewer at the New York Times, and he read a book and didn’t like it, and if he wants to tell on himself on a blog or facebook posting—or a tedious conversation at a cocktail party of whatever the fuck people like him do—that’s fine with me. He should! If you don’t like things, you should say so, even if you’re wrong.

However! Something weird happened when this individual–named “Dwight Garner”–took to the pages of the “paper of record” and wrote the New York Times’ book review of Milkman; he put himself in the position of speaking authoritatively about a book–threw himself into the role with real gusto, in fact–and declared that he would not “recommend it to anyone he liked.” This is fair. However, by wishing this novel on his enemies, I find myself craving to be his enemy, to cry out challenge and to crave combat. Sir! You are WRONG!

Presumably he had to write this review because it won the Booker Prize, so his declaration serves as a very particular kind of utterance: OK, It Won The Booker Prize But It Is Bad. Maybe he had a favorite on the list; maybe he was bummed that they didn’t give the Booker to a book he liked more. And if it were just some book, then he probably wouldn’t have had to review it at all–the New York Times doesn’t review lots of books, the vast majority of them, in fact–and he probably wouldn’t, in turn, hold such a grudge for having had to read a book he thought was “interminable.”

That word, “interminable,” tells you about the dull need to FINISH AND ACCOUNT FOR a book that you’re not enjoying. Books you have to read for school or work are interminable. Books you read for pleasure, enlightenment, or distraction, well, they can’t be “interminable,” because you can just stop reading them.

Before I was a bookseller, I was a freelance writer, of book reviews among other things. There’s a somewhat neglected AaronBady.com out there, filled with links to book reviews I’ve written, and almost all of them are glowing: if I was going to spend time on a book–if I was going to not only read a book, but write about it–I wanted to write about a book that I had things to say about, and I only have things to say about books that (in my humble opinion) are worth reading. Books that I have nothing to say about, that I didn’t finish, well, maybe you’ll like them, but then it’s on you to say why; I’m busy reading something else.

The need to bring a book down to earth comes from an angry feeling that some book has gotten uppity, has received praise it does not deserve, or a book you resent having been impelled to read. But who is impelling you to read things?

The upshot is that this bad review that made me so angry, well, it emerges in a social context, a presumption of cultural authority that, when you read his review, you get sucked into taking seriously. Unasked goes the question of why you or I would turn to a newspaper that employs David Brooks and Ross Douthat as an arbiter of cultural value; instead, the fact that the New York Times panned the book is the story we find ourselves telling, a story more about that august institution than about the book itself.

(Before I was a freelance writer of book reviews among other things, I was an academic, which meant I both had to read things and as a teacher I made other people “have” to read things. I no long have to read things, nor do I have any power to make people read things, and this is generally an improvement. But I still respect cultural authority, more than I should; I can tell, because I’ve several times read a review that makes me very angry. For some absurd reason, it matters to me.)

My story of this book is different than Dwight Garner’s because no one told me to read it; my story is of a book that I’ve picked up and read a bunch of times and always found fresh and thought-provoking and pleasurable and so on. I’m not in a rush to finish it, so I haven’t; I’m not trying to review it for you. Read it yourself, if you want to know what it’s like. You can find it in your local bookstore, or you can read the opening here. You will be able to tell pretty quickly whether you’re going to like it or not. If you’re not the kind of person that will like it, well, my advice to you would be neither to buy it nor read it. Read something you’re more likely to like; Pam told me that Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow is really good, and a lot of customers came back and confirmed that they really enjoyed it.

But it’s not just that Dwight Garner is wrong, according to me; it’s that his “review” is nothing of the sort. It can’t be. How can you “review” a book as if it were an object subject to cost-benefit calculations, as if there was some stable measure of quality and value? A book is not that thing you paid for and hold in your hand; a book is the experience of laughing out loud and trying to explain why you laughed, and failing, and walking away from the book thinking about how paranoia and fear affects pleasure, and never forgetting the image of an eighteen-year old girl abruptly confronted by her paramilitary stalker just as she’s sawing off the head of a dead cat for reasons even she couldn’t adequately supply. But it makes me mad when people think that a lengthy IMHO should be, in some authoritative fashion, a judgment on a book’s worth. And though NYT reviews never mean much for sales, as far as I could tell–whereas an NPR segment will really get Oakland’s book buyers in a lather–the authority of The New York Times Book Reviewing Apparatus does trick people into thinking that what they’re getting is talk about books. It tricks you into thinking that “Dwight Garner” is somebody whose opinion you value and esteem.

What you’re getting is clickbait that pulls your eyes onto a page, an experience which the New York Times can use to sell ads to companies that want to monetize your particular attention span. Lucas told me on the Popula slack yesterday–when we were chatting about this thing I’m writing about reading Milkman–that his partner’s mom

“has this whole thing about how the reviews in the NYT book review have always been filler, vehicles to sell the splashy book ads, how “everyone” has always known they’re garbage, etc. which is funny to think about — dwight garner becoming an ENTITY on his own, in a single review that gets tweeted and pointed at and obsessed over, vs just like…being the dude who fills the space next to Knopf’s spread hyping the latest Dan Brown novel or whatever.”

And it sort of pulled me up short. Why would I get so mad at Dwight Garner for writing a bad review? He is not someone whose opinion I value and esteem, certainly, but that’s mainly because I’ve never met the man, so why would I value and esteem his opinion? Why would I get mad at him for the structural impossibility of the genre he’s paid to write in?

I guess what makes me mad–and this is truly not Dwight Garner’s fault–is when I realize that the thing I was expecting, a sensitive and insightful set of observations about a book, is not being delivered; I get angry because I’m suddenly confronted with a badly-used exercise of cultural authority by a paper of record that gets called that because it calls itself that and for some reason we’ve all agreed to pretend they’re right. I get angry because in those moments when you realize you played yourself by caring about the wrong thing, it’s a lot more fun to get angry at “Dwight Garner,” whoever the hell that is.

I’m Still Reading Milkman by Anna Burns but on my own time, dammit

You can understand why Books Writing treats reading as consumption, why the review, as a genre, treats a book like a commodity: an object whose qualities you, the consumer, will need to know more about in order to make an informed rational-consumer style decision about whether to purchase and adorn your house with. You can also understand why reviews privilege novelty: bookstores primarily stock just-published books–and a relative handful of perennial sellers–and so reviews exist to help you, the informed and rational consumer, manage this flood of publications. That’s what reviews are: they are published in a context, and that’s a context in which Evaluating New Commodities On The Marketplace is the problem being solved.

(That’s a big part of why we, at Popula Dot Com, do not run reviews. Who needs that? We are not concerned with the consumer’s problem of un-evaluated commodities, nor are we tied to the novelty of “news.”)

I’m still reading Milkman. And if you want my opinion of Milkman, I’m happy to give it: I think it’s very good! But why would you want to know what I think about the quality of this book? I bet you’re only mildly interested in whether I think this novel is good. And that’s because you probably know what booksellers learn, but what review-writers are programmed not to know: that everyone is so different from each other, and everyone’s experiences of books are so different from each other, that the idea of an authoritative review of a book is pretty silly. Turning books into commodities is a transformation that booksellers sometimes think more sensitively about than do reviewers or academics, whose structures of authority require them not to; it’s like frog dissection, about which I’ve seen E. B. White quoted as saying “you can do it, but the frog tends to die in the process.” The person doing the dissection–that’s the bookseller in this analogy–tends to be a lot closer to the life being lost than do the people more concerned with the data that gets produced.

Is the customer the frog being dissected? Or the book? I dunno, I’m letting it go. But talking about books can be interesting because other people are so interesting, and books are like an intense and rich way to talk about other people, and “talking to other people about talking about other people” is a pretty workable hard-and-fast definition of “culture.” And because I am so interested in knowing what other people think of this novel, what parts light them up and why, I want to tell them to read it. This book interests me! But that’s why I’m now going to stop writing and go read it some more.

Aaron Bady