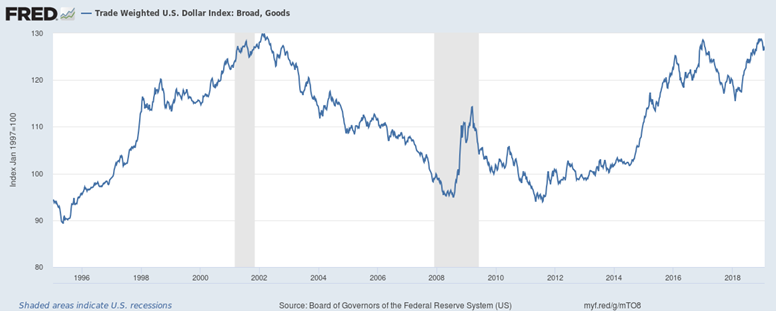

Whenever there is a crisis in the world, the dollar goes up. In financial circles, this is known as a “risk off” trade or, in older terminology, “flight to quality.” Things get hot, money people flee those tin-pot foreign currencies and rush to dollars as a “safe haven.” In a crisis, what else would you do? You wrap yourself in the warmth of the US security blanket, you shelter from the storm in the good old rock solid US dollar.

Strangely, this happens even when the US itself is the source of the crisis—as, for instance, when US subprime mortgages trigger a financial meltdown: After years of declining under Bush II, the greenback took a rapid leap upward after the Lehman debacle as investors ran for cover to the largest and safest economy in the world.

The really odd thing is that this happens, sometimes, even when the US government threatens to default on its debts—that is, politicians refuse to pass an increase in the debt ceiling.* So you want to lend money to a country that can’t pay you back?

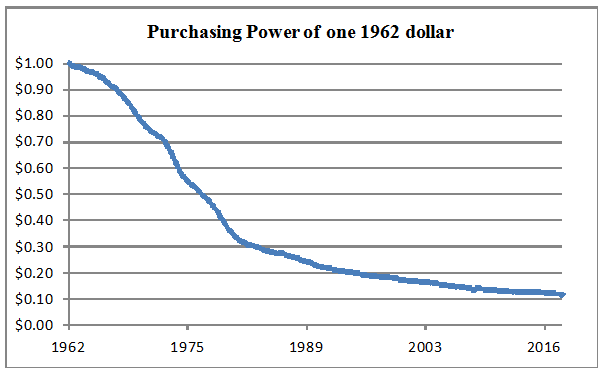

There is anyway something fishy about the whole idea that the dollar is a safe place to keep your savings. Here is what has happened to the purchasing power of the dollar since 1962:

That hard-earned dollar from January 1962 would, by December 2018, be worth roughly 12 cents in 1962 purchasing power. Or to put it another way, what you could buy for $1 in 1962 would cost you about $8 today.

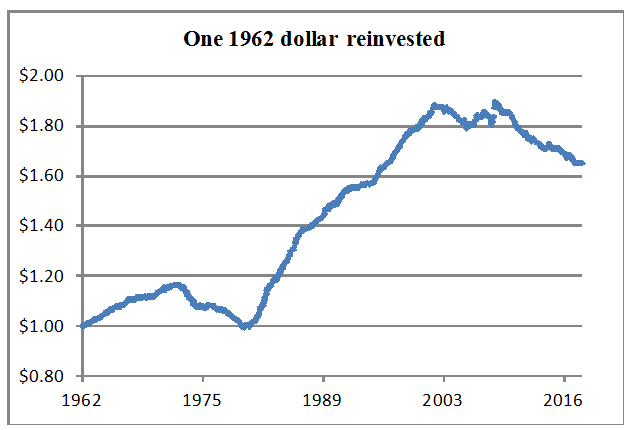

This is, admittedly, slightly deceptive: If you really intended to keep your dollar for all those years, you would probably have invested it. And if you invested it each year in a one-year Treasury bill, then this is what you would have now, in 1962 dollars:

The 65% return works out to about 0.9% a year, compounded.

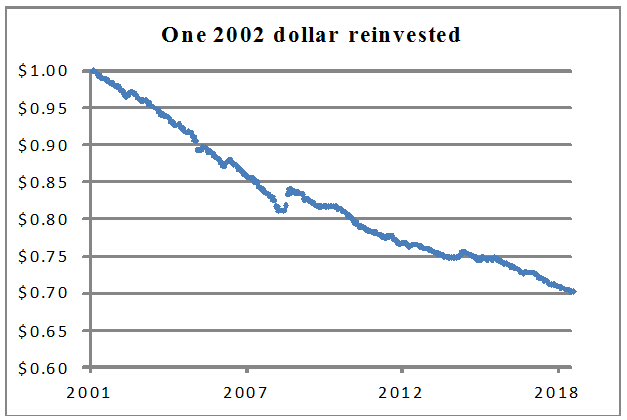

You’ll notice, though, that even reinvesting hasn’t helped since about 2002, because even though inflation has been low, the interest rate on the one-year Treasury bill has been even lower:

So the world’s safest asset was safe? Not safe? You decide.

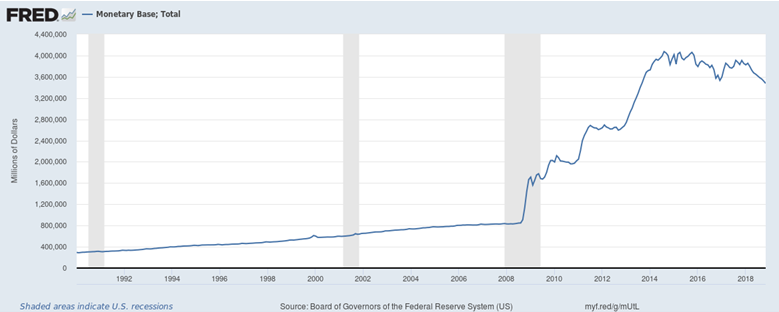

Here’s another funny thing about the dollar: when it needs dollars, the government can just print them. For instance, it needed a lot of dollars during the financial crisis in order to bail out the banks, and look what happened to the number of dollars out there:

After decades of growing relatively slowly, in the course of a few years following the meltdown the “monetary base” more than quadrupled, peaking at around four trillion dollars.

Economists talk a lot about how this doesn’t matter. Despite the flood of money, there hasn’t been a Great Inflation (except in real estate and financial market prices). Unemployment is low, even if most jobs suck. The economy is growing—albeit mostly for the benefit of the 1%, who are, after all, the ones paying the economists. But doesn’t it seem odd that the “safest” asset is a piece of paper, or an entry in a digital account book, that can basically be printed up on a whim? Whatever the eggheads say about this, it seems… rum.

What you need, ideally, is an asset that can’t just be conjured up out of thin air by some banker or politician. Something which is naturally limited in supply. Something enduring. Something imperishable. Something you can put away and rely on to be there, still intact, in twenty or thirty years, undiminished by rust or tarnish, not turned to vinegar, ash or dust by bacterium or flame, mold or moth.

Gold, for instance. It is hard to think of anything quite as good as gold in this respect. And it is this quality of incorruptible endurance and rarity that has made gold a favorite asset for quite a long time: It is about 6,000 years, they say, since people first started mining it and, shortly thereafter, using it, in the form of gold ornaments and bars, as a medium of exchange. The first gold coins were supposedly minted by the Lydian king, Croesus, much more recently—only about 2,600 years ago, in what is now western Turkey.

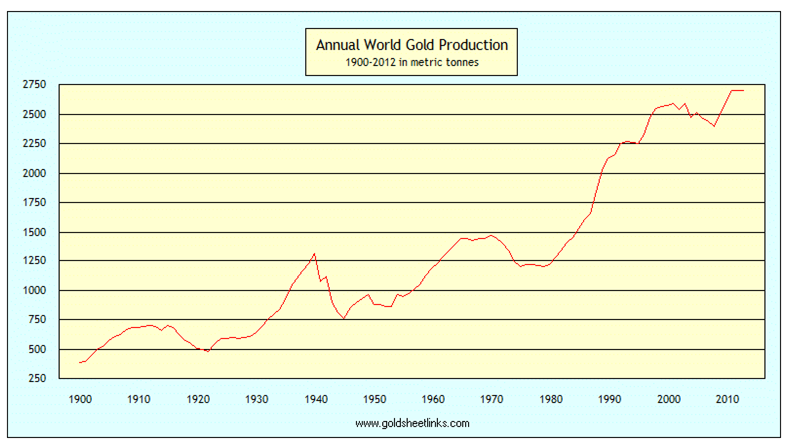

Because it came to be so prized, alchemists tried for centuries to create gold out of lesser metals, but so far nobody has come up with a way to conjure up the stuff except by digging it out of the ground. (Nature has a way, but it’s not one even our best physicists can easily implement.) Since you can’t make gold the same way the banking system can create money, the world stock of gold increases only slowly—by about 3,000 metric tons (kilograms), or probably a modest one and a half percent-ish of the total stock, each year. If the alchemists, physicists or central banks were to succeed in creating it, gold would naturally become much less valuable. That is, really, the whole point.

As to putting a value on gold, though, there’s a puzzle. Most assets, like companies or buildings or government bonds, throw off a certain amount of cash over time, and you can put a value on them based on (a) how much you think this flow of cash might grow or decline in the future, (b) how confident you are in this prediction and (c) what other asset you might buy instead. But in the case of gold, there’s no cash flow, and you have to come up with some other way to put a value on it. (Bitcoin is similar, which is why some call it digital gold).

Just like the US dollar, gold tends to go up against the world’s currencies (at least other than the dollar) in times of crisis. It also rises with expectations of inflation, and falls when interest rates go up, because the money you put in gold could be earning interest. Interest rates also tend to go up when inflation is high, so there are cross-currents here.

There is one approach which arguably gives you some guidance on the long-term value of gold, however. How much does it cost to get it out of the ground and into the vault? If gold were to fall below that price, miners would have to stop mining, and the price of gold would then creep back up to a level where mining it was once again profitable. The mining cost might be a long-term floor.

So how much does it cost to mine gold? There is no easy answer except: A lot.

First, you have to find it. They reckon only about 0.0002 percent of the earth’s crust contains gold in economically recoverable quantities. You might think of gold mining as a matter of digging up some dirt and picking out the shiny bits. It’s not like that at all. The low hanging fruit of gold mining (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre style) has long since been picked. What remains is very thin on the ground, even in areas where it is economically viable to mine it. The amount of gold you can get out of ores in the US averages about 1.5 grams per metric ton. So to get one Troy ounce of gold (31 grams), you have to dig up and crush about 21 tons of dirt. (A Troy ounce, supposedly named after Troyes in Northeastern France where in the Middle Ages there was an annual trade fair, is about ten percent heavier than the avoirdupois version).

Whether it’s in open pits or down mine-shafts (a lot more complicted, obviously), there’s a massive amount of earth to move. It’s loaded onto trucks (up to 200 tons per load in open cast mining) and taken to be crushed and ground. You begin to see why this is an energy intensive business. There are many different ways to extract the gold from the dirt, with different types of ore treated in different ways. Most of them involve quite a bit of water and some cyanide, which is one of the few chemicals you can use to persuade gold to dissolve, resulting after a period of days, weeks or even months in a “pregnant solution” from which the gold can be precipitated, smelted and sent for further refining.

The publicly traded gold mining companies publish some numbers on how much it costs them to produce their gold. They use a measure called “all-in sustaining cost per ounce”, which is supposed to show all the expenses involved in producing gold and maintaining the mines’ production. For the six biggest public companies – Agnico Eagle Mines, Anglo Gold, Barrick, Gold Corp., Kinross, and Newmont Mining, the range in 2017 (the last full year on record) was $750 to $1,087 per ounce.

This suggests an answer to the conundrum of valuation: Gold shouldn’t go below $750 an ounce.

There is, though, a small fly in the ointment: if it costs around $750 to $1,100 an ounce to mine gold, then with gold prices around $1,200 to $1,300, the mining companies must be coining it. Right? Well, not really. From 2015 to 2017, when gold prices were $1,160 to $1,260, the big six collectively lost about $5.5 billion. Even if you exclude a special “impairment charge” of $3.9 billion at GoldCorp., the group lost $1.6 billion. With a combined production of a little over 66,000 ounces for that period, they lost about $24 an ounce.

But that’s not the whole story. The thing about “earnings” and “losses” as reported by any company, and maybe especially natural resource companies, is that the accountants have quite a lot of discretion in calculating these numbers. (That’s partly why a company like GoldCorp ends up having to take a huge “impairment” charge). In any one bad year, they will tell their shareholders that mining is a long-term business, requiring big capital outlays which see no return for years and years. You need to take a long-term view, overlook these short-term blips: Have some patience.

That would be true, if it were true. But if you “follow the money” it’s a questionable claim. When you forget about “earnings” and just look at how much actual cash these companies made over the long term, well, let’s say you’d need more patience than a saint. From 2003 to 2017 inclusive, these six companies saw almost $6 billion of cash leave their bank accounts. (At one point it was much worse: from 2003 to 2013 it was almost $22 billion).

The real cost of mining gold must be higher than the $750 to $1,100 that they say it is. They don’t want to say so, perhaps, because then it might be hard to persuade investors to fund them, but if the cost were really that low, these companies should have been much more profitable. On the back of an envelope the number comes out around $1,200 just to break even. Throw in an extra $100 or so to provide a real cash profit, and you get to $1,300—pretty close to today’s price.

People who advocate buying gold have a distinctly dodgy reputation. You can easily think of them as being like “preppers”—kooks who store food, guns and ammo in underground bunkers in New Zealand, with generators and a supply of fuel, laying in their provisions for the apocalypse, including a bomb-proof safe full of Krugerrands.

Screenshot: YouTube

Screenshot: YouTubeMaybe what makes their taste for gold a little kooky isn’t so much the hoarding of Krugerrands per se as the idea that anyone in a post-apocalyptic world would want them. But we’re most concerned here with the prospects of a messed up but non-apocalyptic world where the inhabitants continue more or less to practice normal commerce rather than acting out Lord Of The Flies.

Just a week or so ago, the chairperson of a government advisory body called the Treasury Bond Advisory Committee wrote a letter to our not very esteemed home-forecloser-turned-Treasury-Secretary, Steven Mnuchin, to announce that the US will have to issue somewhere around $12 trillion of bonds in the next decade. (That’s what happens when you slash taxes.) If there’s a recession, they warn, that figure will be higher. And if history is any guide, the main buyer for all this new debt will be, you guessed it, the Federal Reserve Bank. In other words, they’ll just print up some more dollars. The idea might eventually take hold that, contrary to the strangely widespread belief, the U.S. dollar is not so safe after all. That might be a good time to own some gold.

* The next deadline for Congress to pass an increase in the debt ceiling, incidentally, is March 1st, and depending on how high receipts are in tax season, analysts reckon a crisis could come around again by August.

Disclosure: the author owns a little gold through an Exchange Traded Fund