You probably “know” that Eskimos have over fifty words for snow. And you probably also know that this is somehow wrong.

You might not know why you know this, or remember when you first heard it, or if it’s exactly fifty, or a hundred, a dozen, or just “a lot.” I bet you aren’t very confident in this knowledge; what do you know about “Eskimo” languages? Probably nothing! You probably also know that you know nothing. But if you’ve heard that “Eskimo” is an offensive term—and it’s the kind of old colloquialism that’s so common and American that it must be racist, right?—you might struggle to explain why.

Knowing that you don’t know something is different than knowing what the something is that you don’t know. It might be bullshit, but it’s still there; it doesn’t have to be true to have mass and take up space. “Eskimos have fifty words for snow” is one of those things that people say, a phrase that will go on living in your brain, unused but not thrown away, buried at the bottom of the drawer like a power adaptor to a console you no longer have but will never quite rid yourself of. And when we hit something like this—when we run aground on this point at which all we know is what we don’t—we discover something interesting: just as knowledge has substance, shape, and structure, so does ignorance.

I am statistically safe in presuming that this “we” and “you” I’ve been using is, you know, you. But it’s also me, and people like me. You are probably, in other words, not a person who’s ever been called “Eskimo.”

If you are, welcome! But in that case, you probably know far more about this than I do. You don’t need me to explain this; you already know that “Eskimo” is basically an outsider word, and it will not be novel information that in-group names like Aleut, Inuvialuit, Iñupiat, Kalaallit, Nunavut, Nunavik, Nunatsiavut, and Yupik are usually the first reference point. If you know that “Eskimo” is not a word in any Inuit or Yupik languages—and that, because it is supposedly derived from “eaters of raw meat” in Cree (or from an Ojibwa word meaning “to net snowshoes”), but definitely not from any of the languages of the people so-called—many consider the phrase to be offensive. You may know that “Eskimo” is less offensive in Alaska than in Canada and that even though it was founded as “Pan-Eskimo” organization in 1975, the Inuit Circumpolar Council declared in 1977 that the word “Inuit” would describe and represent the Arctic peoples of northern Canada, Alaska, Siberia, and Greenland; you may know that the reason for this is that all of the “Eskimos” in Canada are Inuit, but that while some native Alaskans are Inuit, some are Yupik and other non-Inuit groups.

In any case, whatever the term’s etymology and historical connotation, the function of “Eskimo” is to generalize, to lump together the indigenous people of the Arctic circle. And such lumping-together gestures have a history: “Eskimo” is the word that Robert Peary used when he brought Franz Boas six human beings from Greenland to display at the American Museum of Natural History—after which four quickly died—and it’s the word Robert Flaherty used to describe the people portrayed in his 1922 documentary, Nanook of the North; it’s the reference point for “Eskimo kisses” or “making igloos” or any number of other idiomatic practices that people use in English to describe practices and activities that they know only through exotic images and spectacle. It’s a brand of ice cream.

“You” is often a euphemism for “me and people like me.” We have a lot of words for ourselves: “you” is one of them, as is “us” and “people.” So let me start again, bearing in mind that, among the words that people like me have for people like me are words like “you” and “we” and “people.”

“Eskimos Have Fifty Words For Snow” is less a description of indigenous linguistics than it is a piece of my, our, or your cultural heritage. It’s “idiomatic” because you know it without thinking about it, but it’s an idiom that helps you think a particular thing: the idea that every culture has particular linguistic constructions to express the ideas and notions that it requires for daily life at the appropriate level of complexity. (It is, in other words, an example of itself.)

“Jargon” gets a bad rap: hyper-specialized occupations have hyper-specialized words, though we respect some kinds of expertise more than others. When doctors or scientists use abstruse and polysyllabic terms, no one minds (or even notices); we tend not to call it jargon. If you believe in the thing the words are describing, that that’s just what that thing is called. By contrast, when doctors of philosophy or social scientists or social justice activists use jargon—a word like “heteronormative,” for example—they are liable to be called “elitists who need to use Plain Language.” The word “jargon” gets used in this pejorative way for the latter group, in other words, because its etymological antecedents—jargon etymologically means the chatter of birds—reflects our antipathy for these alienating words.

The story about Eskimos, by contrast, lets us imagine—by displacing it onto a mythical, exotic people we only know from media images and idioms like this one—a situation in which a necessary (and non-elitist) jargon is matched to its context, organically flowing out of an environment and its human use. It’s a picture of cultural knowledge as a site of general understanding, rather than alienation.

Okay, but you might be asking . . . do “Eskimos” (which we must put in quotes now) actually have over fifty words for snow?

I wondered this too. One way to answer the question would be to google it, which I did; one of the first things you get is this 2013 Washington Post article, whose headline explains “There really are 50 Eskimo words for ‘snow’.”

If you get stopped at the paywall or you’re not that interested, well, mystery solved. If you read the article, you will learn that although some (nameless) anthropologists have called it a hoax, a duo named Igor Krupnik and Winton (Utuktaaq) Weyapuk have more recently “charted the vocabulary of about ten Inuit and Yupik dialects and concluded that they indeed have many more words for snow than English does.” If you want to read Krupnik and Weyapuk’s article, of course, you’ll need to purchase it for $29.95—or buy the book for $80—but most people will, at this point, go away moderately confirmed.

You will learn some nuances from the Washington Post, though; you will learn that the “Eskimo family of languages”—a family of languages that circles the arctic from Alaska to Siberia to Greenland to Canada—has two main branches, Inuit and Yupik, with Aleutian a more distant relative, which means that the formulation “Eskimos have” blurs language and people. (If you speak English, does that make you “English”?) And you will learn that while each language in the “Eskimo” grouping has its own unique vocabulary, all of which do tend to be more sophisticated and nuanced for snow and ice than English, the warrant for declaring the statement true is almost totally attributable to the underlying linguistic structure of this group of languages: if they have fifty words for snow, it’s because they can have as many words as they want for almost anything. All “Eskimo” languages form words very differently than English, having in common a feature called “Polysynthesis,” which, as the Post explains, “allows speakers to encode a huge amount of information in one word by plugging various suffixes onto a base word”:

“This makes compiling dictionaries particularly difficult: Do two terms that use the same base but a different ending really represent two common idioms within a language, or is the difference simply a speaker’s descriptive flourish? Both are possible, and vocabulary lists could quickly snowball if an outsider were to confuse the two.”

Note how the words “snowball” got used there: a word that means one thing can be made—by the power of metaphor, familiarity, and convention—to mean something completely and utterly distinct. How language is used is more complex than the question of counting up dictionary entries: if you and I were to need a word for the way a process can accelerate exponentially—building on itself and gaining speed—then the word “Snowball” can and will be pressed into service to describe how vocabulary lists might grow unmanageably large.

But let’s put this aside for a moment, along with Krupnik and Weyapuk, the two anthropologists that the Washington Post relies on to declare that, in fact, “There really are 50 Eskimo words for ‘snow’.” Instead, let’s look to the two anthropologists who, in the 80’s, called this thing a hoax, a pair who the Washington Post article goes to the trouble of correcting, but leaves them curiously unnamed. Their very clear and decisive answer to the question is: Nope. And fuck nope!

First, Laura Martin argued in the early 80s (in American Anthropologist) that the idea of Eskimos having an hyper-developed vocabulary for snow and ice was essentially a fallacy that became popular through a series of de-contextualizing excerpts. There is a passage in the introduction to Franz Boas’s 1911 Handbook of American Indian Languages that mentions Eskimos having four different words for snow, the first reference to this sort of thing that she can find:

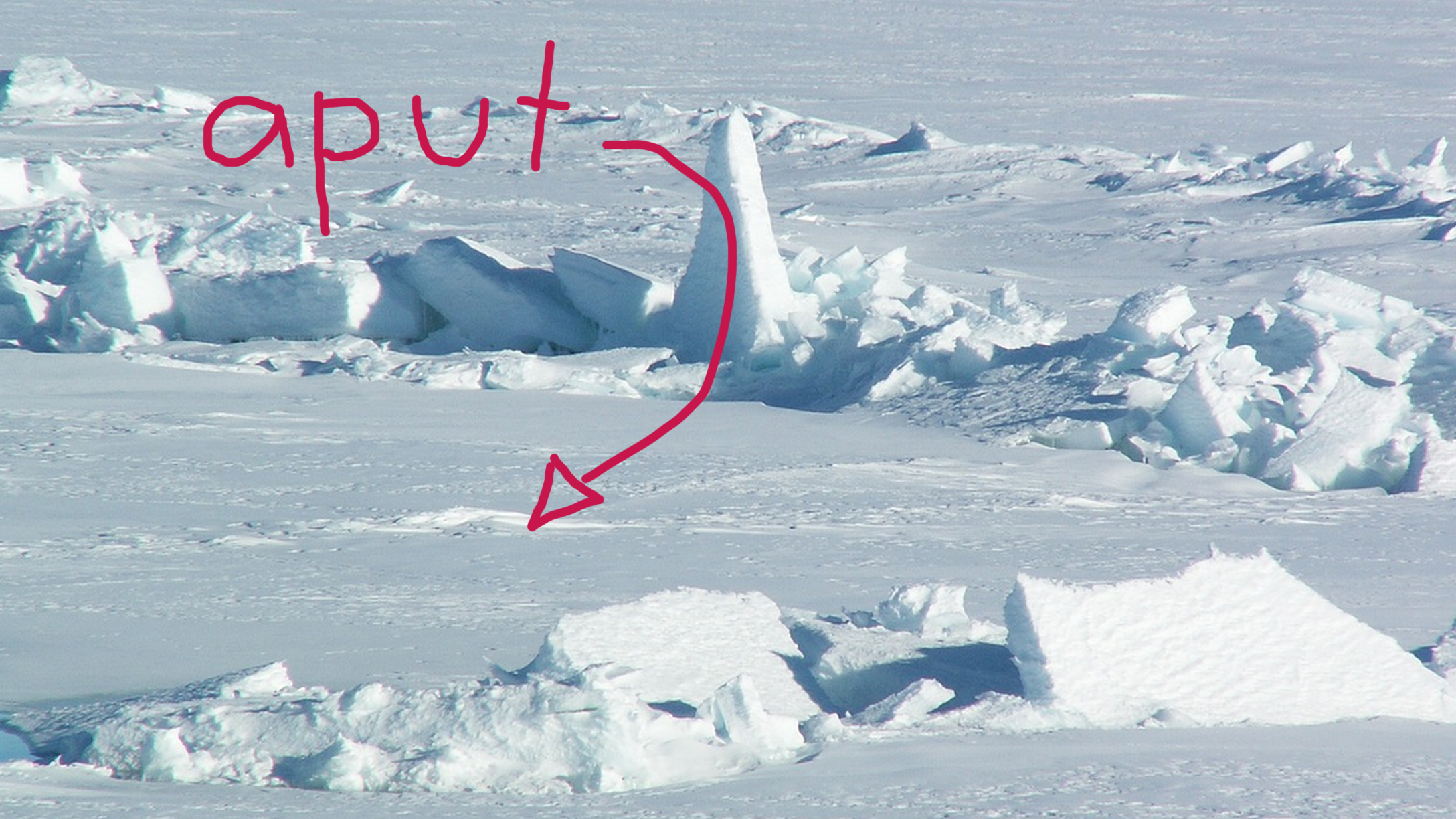

“the words for SNOW in Eskimo, may be given,” he writes, “Here we find one word, aput, expressing SNOW ON THE GROUND; another one, qana, FALLING SNOW; a third one, piqsirpoq, DRIFTING SNOW; and a fourth one, qimuqsuq, A SNOWDRIFT.”

As far as it goes, this is fine (for early 20th-century linguistic anthropology). But as Martin tells the story, what happens next is that Benjamin Lee Whorf—best known for the “Sapir-Whorf” hypothesis of linguistic relativity—took this short list of words and in a popular 1940 Technology Review essay called “Science and Linguistics,” used it to tell the following story about Eskimos:

“We have the same word for falling snow, snow on the ground, snow packed hard like ice, slushy snow, wind-driven flying snow—whatever the situation may be. To an Eskimo, this all-inclusive word would be almost unthinkable; he would say that falling snow, slushy snow, and so on, are sensuously and operationally different, different things to contend with; he uses different words for them and for other kinds of snow.”

Whorf doesn’t cite any sources for this—and he didn’t speak any of those languages himself—so Martin assumes he got it from Boas but didn’t really know what he was talking about; that he took the fact that four (aput, qana, piqsirpoq, and qimuqsuq) is more than one (snow) and used that to argue that language radically constrains and determines thought. To an “Eskimo,” Whorf explains, having only one word for snow (as we do) would be “unthinkable” because what we can think is a function of what our words give us vehicles to think it in.

This deterministic relationship between thought and language is, more or less, what people mean when they say “the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis,” a question that still divides linguists: to what extent is language use both culturally bound and binding? To what extent does language constrain what is thinkable, and make new thoughts possible? Martin’s attempt to debunk the myth of Eskimo snow vocabulary also chips away at the use she says that Whorf was making of it, his assertion that “Eskimos” would find our language use as unthinkable as we find theirs; he is asserting a strong relationship between Eskimo words for snow and the worldview, culture, and cognitive capacity associated with it..

Her major point is a strong one: if we look at what Boas wrote—who, unlike Whorf, had a relatively firm linguistic grounding in the languages in question—we find that instead of describing a peculiar characteristic of “Eskimo” language, he was describing a characteristic of literally all languages. Before he talks about Arctic snow, for example, he talks about Anglophone water:

“To take again the example of English, we find that the idea of water is expressed in a great variety of forms: one term serves to express water as a liquid; another one, water in the form of a large expanse (lake); others, water as running in a large body or in a small body (river and brook); still other terms express water in the form of rain, dew, wave, and foam. It is perfectly conceivable that this variety of ideas, each of which is expressed by a single independent term in English, might be expressed in other languages by derivations from the same term.”

It’s only a few lines later that Boas introduces Eskimo snow, as “another example of the same kind.” Which is to say, while Boas was comparing and analogizing English and Eskimo vocabularies—noting how every language has specialized areas of lexical complexity—Whorf is drawing a sharper contrast. Rather than making a statement about all languages, from English to the “Eskimo-Aleut” family, Whorf is distinguishing between our language and theirs, highlighting some features that makes theirs unusual (and using ours as the transparent vessel for describing that).

For Boas, every language has its own unique features and complexity but nothing, in that account, would prevent Eskimo-speakers from learning English words for water or English-speakers from learning Eskimo words for snow. But Whorf takes that idea and emphasizes a mutual incomprehension flowing out of this difference: our singular term for snow “would be almost unthinkable” to an Eskimo, he suggests, and then hypothesizes an Eskimo who helpfully explains why he can’t think it, using phrases like “sensuously and operationally different.”

This is a strange story, if you think about it. You’re not necessarily supposed to think about it (remember: idiomatic is a word for saying something without thinking about it). But isn’t it odd that this Eskimo can explain the insufficiency of the single word “snow”? That he finds our language “almost unthinkable” while knowing it well enough to explain this precise fact to us? It’s also strange that Whorf posits this story as hypothetical, that “this all-inclusive word would be almost unthinkable.” (Has no Eskimo ever learned English?)

Because the Inuit-Yupik-Unangan family produce “words” differently, “The structure of Eskimo grammar means that the number of ‘words’ for snow is literally incalculable,” as Martin observes, so that the number of words for anything could also be incalculable. But is “plugging various suffixes onto a base word” really that different from the way English gets “falling snow, snow on the ground, snow packed hard like ice, slushy snow, wind-driven flying snow,” which are also new lexical units constructed by putting other words together in new combinations?

Benjamin Whorf seems to be saying yes, focused as he was on what people’s languages prevent them from knowing, on how language shapes, constrains, and limits what people can think. And so, perhaps he was quick to produce a just-so story about how those people over there have a language that shapes what they know and can’t know. In this sense, his story is less about the specifics of language than about cultural distance, and if you need a them to serve that linguistic function, the word “Eskimo” is a handy bit of jargon for that task.

Taken in isolation, then, Whorf’s paragraph about Eskimos is a pejorative story about Eskimo confusion, seen from our point of comprehension: as the very act of writing and reading demonstrate, we are able to understand how they have their worldview shaped by language. But as it happens, Whorf wasn’t telling as much of an isolated story about Eskimos as it seems when you excerpt it. The quote story about Eskimos is preceded and followed by similar stories about the Hopi people and the Aztecs: the former call all flying things by variations on the same word, Whorf says, and the latter would call all cold things by variations on the same word.

No one should be surprised that the eccentricities of “the English” never became a thing, of course. We do not tend to confuse “The English” with “speakers of English” for the same reason that there is no common-sense idiom about how their many words for water are derived from centuries as a seagoing empire based on a rainy island. They do not become a they because they are us.

At the same time, “did you know that the Hopi only have one word for flying things?” never became a thing either, nor did “did you know that the Aztecs, etc.” And the reason is pretty random, basically; as Martin shows, “Eskimos have fifty words for snow” became a thing because that particular example was taken in isolation: it was cut out of Whorf’s article and propagated through a series of textbooks that were much sloppier than Whorf, from whence it has gone on to become an exotic story about an exotic people. As she runs down how this happened, Martin primarily blames Roger Brown’s Words and Things (1958) and Edward Hall’s The Silent Language (1959), textbooks which help transform Boas’s specific statement about Eskimo languages into an idiomatic figure for a Whorfian point: against the backdrop of what students know about English, “Eskimo” linguistics figure as an exotic example, demonstrating what is counterintuitive about language (while English remains the transparent vehicle for explaining it).

And so, as Martin tells it, Boas’s lexical fact become Whorf’s story about incomprehension and finally, in Brown’s and Hall’s textbooks, become a parable of exotic others, which, as it has been propagated across society at large, has become, simply, a fallacy.

A few years after Martin’s essay was written, linguist Geoff Pullum got angry that no one seemed to be reading her. “Once the public has decided to accept something as an interesting fact,” he observed in “The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax,” “it becomes almost impossible to get the acceptance rescinded.” Pullum refers to his article as “little more than an extended review and elaboration” of Martin’s work, but he very intentionally raised the volume of his protest and was much unkinder about Whorf’s lack of expertise and linguistics. He makes Whorf the clear villain, basically an unqualified hack—referring to him as “Connecticut fire-prevention inspector and weekend language-fancier”—and describes Technology Review as MIT’s “promotional magazine,” a statement that might be true, as with his statement about Whorf’s day job, but which hardly captures the whole situation.

But Pullum’s “The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax” did what Martin’s more careful and polite academic text hadn’t: after Pullum, the hoax became a thing. Instead of Did you know that Eskimos have fifty words for snow? It began to be did you know that (actually) they don’t? In The Language Instinct (1994) for example, Stephen Pinker observes that “Contrary to popular belief, the Eskimos do not have more words for snow than do speakers of English” and in 1996, Geoffrey Nunberg could observe that after “the world has had a decade to disabuse itself of the notion that the Eskimos have a multitude of words for snow [and] that the myth is showing signs of melting under the light of Martin’s scholarship and the heat of Pullum’s invective.” By the 2000s, the “myth” was the main thing: sites like “Language Log” basically made it into a running meme for generalized linguistic ignorance and shenanigans, with periodic “Did you know?” articles at places like Buzzfeed and Mental Floss adding to the pile.

“Hoax” and “myth” are strong words, of course. But the backlash is not only about the simple lexical point: Whorf died in 1941 and the “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis”—a term not used by him, or his mentor Edward Sapir—has been much criticized since the 1950s, and Pinker has been one of linguistic relativism’s harshest critics ( as he puts it in The Language Instinct, “the more you examine Whorf’s arguments, the less sense they make”). And yet to claim that “Eskimos do not have more words for snow than do speakers of English,” as Pinker does, demonstrates more of an investment in what Whorf said than what speakers of the languages in question say: because Pinker (and the others in this backlash) are so eager to take down the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, they end up making claims that are equally problematic. After all, just as the incommensurability of the different languages means you can’t say that “Eskimos” do have more words for snow than do Anglophones, it also means that you can’t really say that they don’t.

It’s in this context that the Washington Post read Krupnik and Weyapuk’s article and discovered that, in fact, it’s not such a hoax after all. Martin and Pullum (and then Pinker) wrote what they wrote at a time when the general understanding was that Eskimos Have 50 Words, but Krupnik and Weyapuk wrote theirs at a time when the pendulum had swung back, when the more general understanding was that Actually They Don’t. Against that background, the fact that they were able to document “more than 120 local Inupiaq terms for sea ice and associated vocabulary in the community of Wales, Alaska, in 2007–2008”—and that this vocabulary is as rich and complex as it would be expected to be for a group of people whose ancestors hunted seals on sea ice—becomes a story, one that the Washington Post picks up.

But there’s a wrinkle. If you read the actual article—not the Washington Post summary—you will learn that Actually They Do is sort of wrong too. In 2007, “most of the Kingikmiut are now more fluent in English than in their native Inupiaq” and “only people 50 years of age and older regularly speak in Inupiaq”:

“Since the late 1960s, snowmobiles have replaced dog teams; ATV’s (all-terrain vehicles, four-wheelers) replaced walking to subsistence areas; and aluminum skiffs replaced traditional skin boats. Short-wave radios provide instant communication among crews and between hunters and their homes. Global Positioning System (GPS) units supplement or replace compasses and other means of navigation on land and at sea. Some changes were quite rapid (i.e., the introduction of snowmobiles in the late 1960s), whereas other progressed more gradually, like the replacement of skin boats by wooden and aluminum boats over most of the 1970s. In any case, today’s hunters depend heavily upon many types of equipment bought from the outside.

All these changes brought with them new English words that describe the new objects and their function. The changes also triggered a shift in the use of language. During the 1970s and 1980s, English gradually encroached upon and began replacing Inupiaq as the Kingikmiut prime means of communication.”

In such a context, the question is no longer “how many words do they have?” Their project was to recover them, and to share them with younger generations who never grew up with those terms in the first place. While the Washington Post only got interested because of the “Hoax Or Not?” question—which you can see by the way “there are 120 local Inupiaq terms for sea ice” becomes “There really are 50 Eskimo words for ‘snow’”—the real thrust of Krupnik and Weyapuk’s research was producing a bilingual “Wales Inupiaq Sea Ice Dictionary,” one that the community itself could use and learn from. And they did! And here it is.

Where does all of this leave us?

One interesting thing is how boring the answer to the underlying question is. On the one hand, people who live in the Arctic—and whose languages developed in that environment—will naturally have more sophisticated and nuanced and complex language for describing their environment, exactly as you’d expect them to. No one really denies that they tend to, even if this fact isn’t easily grasped by counting words. But exoticizing Eskimos is also a function of ignorance, conjecture, and projection. “Eskimos Have Fifty Words for Snow” is an amazing phrase, because every word in it is wrong. But reversing it—announcing proudly that they don’t—only replicates that wrongness; you can’t say no to a bad question and be right.

There is, however, a much more interesting question that Boas and particularly Whorf were asking: can learning new languages make new kinds of thought possible? That’s worth asking because it’s not about the people of the Arctic circle; it’s a question about us, about what it might be possible to think if we started using the multiplicity made possible by humanity’s multilingual diversity.

If you read up on the “Eskimo Snow Hoax”—if you read Martin, Pullum, and Pinker, e.g., and you read the passage or two from Benjamin Whorf that they quote—it is easy to be dismissive of our moonlighting Connecticut Fire Inspector. He didn’t know any Eskimo languages and that passage makes him seem stereotypically ethnocentric, telling stories about “Eskimo” incomprehension from a perspective that naturalizes a Western scientific point of view. But if you read the essay the passage is quoted from, one finds him telling a somewhat different story, not about Eskimos, but about the limitations of what we might as well call “Western Science.”

Whorf wrote “Science and Linguistics” because he was interested in relativity, a concept popularized by Albert Einstein that’s more epistemological than strictly testable. This is why Whorf didn’t call his idea a “hypothesis” (though those who came after him did): a hypothesis can be tested and challenged and its claims can be disproved. But Whorf wasn’t trying to make a claim about how Eskimos do think; he was describing the humility we should have, as individual speakers of a finite number of languages, when faced with the dizzying complexity of a multilingual world (and using “Eskimo” languages as one of several examples).

“One significant contribution to science from the linguistic point of view,” he writes, “may be the greater development of our sense of perspective”:

“We shall no longer be able to see a few recent dialects of the Indo-European family, and the rationalizing techniques elaborated from their patterns, as the apex of the evolution of the human mind, nor their present wide spread as due to any survival from fitness or to anything but a few events of history — events that could be called fortunate only from the parochial point of view of the favored parties.”

His point, put as simply as I can, is that Science must know some part of what it knows as a silent, unthinking, idiomatic function of the languages shared by scientists: if a Russian, a Chilean, and Welsh scientist can all understand each other—and share their work with their Nigerian and Japanese colleagues—it’s because there are baseline commonalities within those languages, made across thousands of years of commerce and conversation (and shared antecedents). These languages are significantly translatable, in short, because they’ve had to be; shades of dissonance may persist, but science has learned to work across the differences and to embrace and consolidate that which is shared and common.

What if, Whorf asks, we take as our starting point what speakers of one language take for granted—as idiomatic—but others do not? What if instead of focusing on the glass-half-full that is the translatability between languages, we start thinking about the glass-half-empty of what is incommensurably different?

Just as general relativity suggests that perception of the universe will change depending on where you stand, Whorf suggests “a new principle of relativity,” in which “all observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similar, or can in some way be calibrated.” And so, he asked: what can we learn about science from languages, and their speakers, whose perception of the universe is organized by different architectures of meaning than our own?

What’s fascinating to me about actually reading Whorf’s work—after working my way debunkers who gesture at his ignorance as disqualifying—is how simple the point he was trying to make actually was: that ignorance is, itself, a pathway towards new knowledge. Precisely because other languages show us things we didn’t know—and didn’t know we didn’t know—we can learn new things by engaging with that ignorance. What, for example, might an Inuktitut know about a world that distinguishes between aput, qana, piqsirpoq, or qimuqsuq that an America won’t know about “snow”? To translate “aput” into “snow on the ground” doesn’t solve the problem, it only buries it under the illusion of comprehension; better to ask, he says, what it is that isn’t being translated.

His point—the opposite of the one I had expected to find—is that a Connecticut physicist could potentially learn a lot from speakers of “Eskimo” languages, not only because native peoples might know things about how the world works, but because in the friction between different ways of perceiving, we can become aware of the conceptual and linguistic constraints on how our own knowledge can be deployed. For this reason, he closes with an exhortation to “that humility which accompanies the true scientific spirit, and thus forbid that arrogance of the mind which hinders real scientific curiosity and detachment.”

At the end of all of this, what’s striking about the question of “How many words do Eskimos have for snow?” is how little can be done with it. Bad questions produce bad answers, and nothing is as mind-deadening as the confidently presented arrogance of facts reduced to numbers: what could be as irrelevant and useless as the number fifty? And what could be a more succinct demonstration of the Sapir-Whorf principle than a question whose terms and linguistic assumptions close off the very stories it’s trying to tell?

I started off with a google search because—at some point in 2018—I had the sudden realization that I knew this phrase and I didn’t know why. I thought it would be a few days’ research and a quick little explainer essay; I had imagined that I’d come up with a number. But at the end of half-a-year’s peripatetic wandering through this question, what’s been the most interesting discovery is that all the wrong answers are at least as interesting and useful as the so-called right ones. The most confident pronouncements are the least enlightening. But it’s people’s wrongness—when their answers are different because you discover them proceeding from a different set of first principles—that make the world seem bigger and more interesting. Buried in the fact that fifty is wrong is a story about how knowledge is construed through Google’s shallow reach into academic research, a story about how media’s fetish for novelty produces debunking backlashes, a story about how an international word can be offensive in one nation but not another, a story about how textbooks seize facts as examples by draining them of complexity and then propagate that oversimplification, a story about how scholars push back against amateur expertise and defend the citadels of knowledge from relativity, a story about how early twentieth-century ethnography was racist and exoticizing (and also, interestingly, about how it was less so than it can seem from a differently racist and exoticizing retrospective gaze), and a story about languages are not possessed but nurtured and used.

And finally, there’s the story of how Sapir-Whorf is an idea that can’t be debunked or disproven because at the base of it is something harder to dismiss than a fact or a claim: the faith that what we don’t (yet) know is more interesting than what we do.

Aaron Bady