At eight years old, I started dreaming of my perfect nose. It was long and slim with nostrils shaped like teardrops, and a pointy tip which cast a gentle shadow over my top lip which was, I thought, a little too big. I don’t remember what I was doing in the dream. Perhaps I was running the 100m sprint at an international athletics competition, or signing autographs as the newest member of Destiny’s Child following Farrah Franklin’s exit. What I do know is that I felt slight and beautiful. That imaginary nose changed the way I walked and moved. It gave me the grace of a ballerina pirouetting across center stage.

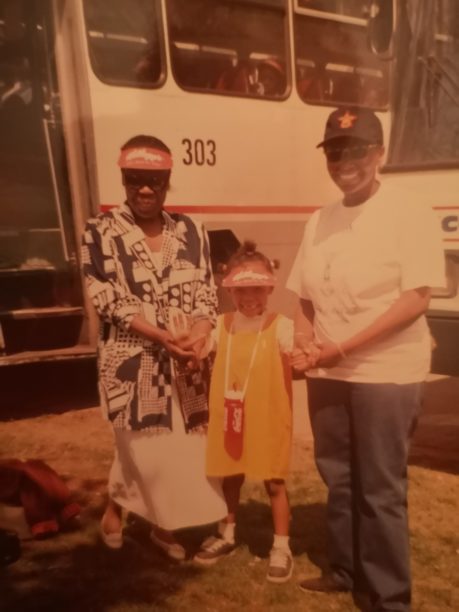

I hadn’t paid much attention to my nose until earlier that year when my grandmother hosted a weekend-long gathering to welcome my uncle’s new wife into the family. When she summoned me to the living room, I left my cousins sitting outside on the stoop where we’d been eating bags of tomato-flavored chips which made our fingertips look like red buttons. The adults were having what my family liked to call “big people talk.” We were never told what these discussions were about, but they usually concerned a wayward older cousin, perennially drunk uncle, or property dispute between distant relatives. I entered the room with my hands behind my back, hiding the evidence of the chips I wasn’t supposed to eat, and avoiding eye contact with everyone but my favorite auntie, whom we called simply “Auntie,” because she always defended us when we got in trouble. What had sounded like conspiratorial whispers just moments ago turned into gasps of joy, as relatives commented on my growth. My father’s cousin, Puleng, asked me whether I remembered playing Legos with her as a baby. I didn’t but I nodded my head at her anyway.

Then, my grandmother asked me to describe her nose, right there, in front of everybody. At first, I was stumped. I’d only taken notice of her nose when she had her snuff. After scooping a mound into her nose, she’d reach for a handkerchief to stop the black snot from running down her lips. My grandmother sensed my hesitation and assured me that she wouldn’t be offended by whatever I said. So I delivered my findings: wide and flat with thick round nostrils that looked like binocular lenses. The room broke into laughter. I didn’t know what was so funny but I was happy to see the adults pleased. After exchanging jokes with her sister, my grandmother urged me to assess the noses of other family members. At first, I was nervous but after some encouragement, I began to deliver my verdict slowly, throwing adjectives at each nose which appeared in front of me. Once I’d finished, my grandmother was curious to know what I thought of my own nose. I hadn’t ever considered that question. Before I could respond, she leaned down, pinched my right cheek, and said it was just like hers. “But don’t worry my girl, you’re still beautiful,” she added, squeezing my cheek a little harder.

In the years that followed this first of what would be many nose verdicts, I was frequently reminded of the number of ways mine just wasn’t quite right. In grade four, a girl nicknamed me “Piglet.” About a year later, my best friend told me how “African” my nose looked, pointing out that unlike her oval-shaped nostrils, mine

Like most beauty standards, the idea of a good nose has taken different iterations throughout history. In Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery, historian Sander L. Gilman writes that during the 18th and 19th centuries, anthropologists believed that black and Jewish noses were signs of a “primitive” and “dangerous” nature. In the late 1800s, Irish immigrants looking to escape discrimination could get surgical procedures minimizing their “pug noses” so they could assimilate into Anglo-Saxon society. While racial stereotypes about the undesirability of black and Jewish noses have remained a constant throughout the 20th century and even the 21st century, Gilman writes that the same pug noses which symbolized Irish inferiority in the late 19th century became the desired nose for young Jewish girls looking to get a more “Americanized” look in the post–World War II era.

In my household, Michael Jackson was the cautionary tale for black people looking to “fix” their features. Whenever we’d watch the DVD of his greatest music videos, my family would always debate where Jackson should have stopped with the plastic surgery. My brother and I would argue for “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough” and “Rock With You,” while my parents believed he should’ve left his Jackson Five nose alone. Yet even as I watched my family’s favorite pop star scrub his face of all its blackness, I still harbored a desire to tweak the shape of my nose.

Two weeks before my 11th birthday, I took some clothes pegs and placed them at the bottom of my nose, hoping they would dent my nostrils. One day a few weeks later, my mother caught me pinching the end of my nose with a clothes peg and demanded an explanation. She reprimanded me for trying to change my “African features” and look “white.” In her eyes, I was not only insulting God, but denying my heritage and, therefore, them. My grandmother had shared stories of how the apartheid government used to measure the kinkiness of their hair, and the size of their lips and noses to allocate people into “appropriate” racial categories. Whenever we got ready for church or the mall, she’d shower me with praise and flattery, reminding me how beautiful my coarse hair, full lips, and wide nose were.

Sometimes it felt like she was trying to convince herself of the fact more than she was trying to convince me. I wanted to believe that these features made me beautiful, that there was some special reason as to why my nose looked the way it did. When I did tell my parents about the incidents where I was teased about my nose, they’d assure me that I’d “grow into it” one day, and that having a “white nose” would make me look horrible. They’d always remind me of my older cousin who had a flat nose but grew into it as an adult. I would feel a flicker of hope until I realized they were most likely trying to make me feel better about something which they were admitting was a problem.

When I tried to have positive feelings about my nose, I felt like I was just doing it for my parents. I felt bad that I hated something which came from them and this guilt pushed me to stop fussing about my nose as much as I had before. But every now and then, when I stared at myself too long in the mirror, flipped through tabloid magazines, or envied how little my friends worried about their side profiles, I couldn’t help but feel my mother and grandmother’s attempts to make me love my nose didn’t hold any weight when thrown up against the realities of the world. None of my family members, other than my grandmother, had noses which looked like mine, which made it harder for me to feel like they understood how much it affected me. My preoccupation with my nose may have seemed like girlish vanity to them, but it was a source of pain and confusion for me. If my nose was supposedly a beautiful marker of my African heritage, why did my grandmother tell me I was beautiful in spite of it? If it was something that was crafted by God, why was it something I’d eventually grow into?

When I hit my mid-teens, the unfairness felt more intense. The social segregation at my high school grew worse by the year, with a group of angry young white boys becoming more verbally abusive towards us black girls. Suddenly the disgust at noses like mine felt like a political cause. I was beginning to undergo the kind of race consciousness which psychologist William Cross identified as “immersion-emersion” in his 1971 essay “Negro-to-Black Conversion Experience.” I used the term “the white man” in casual conversation. I based most of my speeches in English class on the Black Power and Black Consciousness movements. I shaved my head during this time, and pretended it was a political act rather than a suggestion from my hairdresser because I hadn’t taken good enough care of my hair.

As I read more black literature, I noticed how the descriptions of bad noses made them sound a lot like mine. In Toni Morrison’s early novels, The Bluest Eye and Sula, noses were used as shorthand for a black woman’s attractiveness and desirability. In Sula, I saw some of my grandmother in Helene Wright, mother of protagonist Nel, who feels exasperated that her daughter has inherited her father’s “broad flat nose” and “generous lips.” When she recommends that Nel straighten her nose with a clothespin, I felt a stinging familiarity. But unlike Nel, I continued to injure my nose to get the nose Helene Wright knew her daughter needed. Reading The Bluest Eye, I was drawn to the character Pecola, whose awareness of the colorist pecking order brought up some of the contradictions which had confused me. When the narrator Claudia tells us Pecola knew her nose was “not big and flat like some of those who were thought so cute,” it made me realize why I couldn’t like my nose, no matter how much I understood about why I didn’t. I knew about the racial history behind my nose, but I also knew what people liked when it came to beauty. Like Pecola, I was aware of how things worked, but also like her, I couldn’t pretend that they were working in my favor.

As I grew out of those clumsier expressions of racial pride and identity, I started to get mad at how my desire for a new nose was dismissed as self-loathing and racial treason by people who either knew they were lucky not to look like

Self-love is in fashion now, but it glosses over so many uncomfortable truths. I’m 26 now and I want to feel like this is all behind me, but then, just the other day, after taking a horrible selfie, I put clothes pegs on my nose. I felt pathetic and put them away quickly, but not long after, I found myself pinching the tip of my nose to give it a semblance of a bridge. And I still think a lot about getting plastic surgery. I’ve spent many evenings scrolling through the pages of Instagram cosmetic surgeons who offer non-surgical rhinoplasty with the casualness of an influencer selling Fit Tummy Tea. The convenience of these procedures is alluring to me, in that the lack of bandages and recovery time wouldn’t attract gossip and attention. I would just suddenly have a new nose and be happier.

Sometimes I’m fine with my nose. Most times I’m indifferent. I have felt pretty in spite of it, and I have found myself staring at my friends with jealousy because somehow their noses manage to look both black and slim. I know I shouldn’t think about it as much as I do, but I still feel like changing this one thing on my face will stop all the noise in my head. I wish there were more transparency in conversations around beauty. What if there’s some part of you that you know you should love, but you just don’t love it? How are you supposed to feel then? Even though you know conventional standards of beauty are bullshit, can you still be honest about not being enthusiastic about parts of you which the world doesn’t find attractive? I’ll never be able to practice self-love around my nose but I can try something else. I don’t know what to call it, but I’m trying.

Khanya Mtshali