Whenever my parents and I would go to visit relatives in India, we always spent the first night at my uncle’s house in the West Bandra district of Mumbai, because it was nearest to the airport. When we would pull up to his street, we would notice, next door to my uncle’s apartment building, a large stone gateway with a sign reading “Matoshree” and armed guards posted outside. I always thought it must be a government building. It wasn’t until much later, when I returned to Mumbai as a high school graduate, that I learned the building hidden behind the gateway belonged to Bal Keshav Thackeray, leader of Shiv Sena.

Named after the king of the Maratha Empire, Chatrapati Shivaji Bhonsle I, Shiv Sena is a right-wing nationalist political organization which promotes itself as the protector of Hindu and Marathi identity. Marathi people are an ethnolinguistic group of Indians who mostly hail from the present day state of Maharashtra. That may seem confusing to some Anglophone readers. How does a nationalist organization promote identity of the people of a state?

For context, you have to understand that for much of history and certainly before the colonization of the subcontinent by the British Empire, India was a collection of kingdoms and vassal states, each with its own distinctive cultural history, traditions, and language. As Bhiku Parekh describes in Defining India’s Identity, “Indian civilization was plural and included different currents of moral and philosophical thought.” In many parts of India, state identity is held in equal regard to national identity.

Nationalism in India has taken a major upswing in this decade, culminating in the election of Narendra Modi as Prime Minister and the majority control of parliament by the right-wing nationalist Bharatiaya Janata Party (or BJP). This political upheaval is reflected in the overall culture of India. When the government instituted a rule to stand for the national anthem at the beginning of film screenings at movie theaters, Bollywood—the largest film industry in the world—was brought into the center of the nationalism debate. Over the years, Bollywood films have begun to reflect these cultural transformations more and more deeply.

While there has been a strong wave of progressive topics and ideas surfacing in recent Bollywood movies, from environmental consciousness in Nila Madhab Panda’s Kadvi Hawa (2017), to women’s rights issues in Anniruddha Roy Choudhury’s Pink (2016), to criticisms of rising Islamophobia in Anubhav Sinha’s Mulk (2018), there has also been a tide of nationalist propaganda surging throughout mainstream Hindi cinema. This year, January alone featured six movies embodying nationalist pride. Uri: The Surgical Strike, Manikarnika, and 72 Hours: The Martyr Who Never Died are melodramatic idealizations of India’s soldiers fighting against various foreign powers like Pakistan, China, and the British Empire; The Accidental Prime Minister takes shots at the Indian National Congress, the rival party to the right-wing BJP, framing former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s tenure as tainted by his party’s corruption and negligence. But none of these films hits the level of barefaced propaganda on display as in Abhijit Panse’s Thackeray.

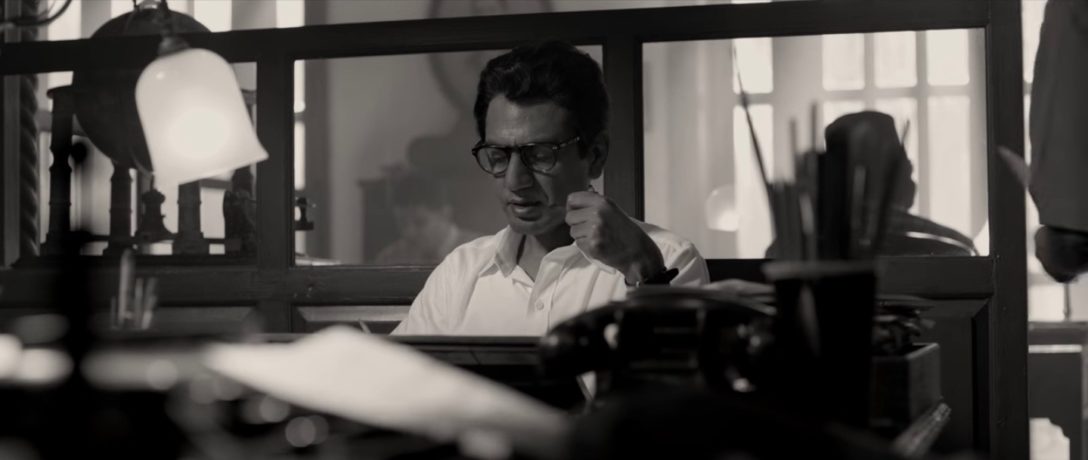

Written and bankrolled by Sanjay Raut, a longtime politician in Shiv Sena and a current Member of Parliament, Thackeray is this year’s most blatantly shameless ad campaign for Indian and Hindu supremacy disguised as cinema. Its opening sequence introduces Bal Thackeray (played by Nawazuddhin Siddiqui) with awestruck celebrity respect of the kind that greets stars like Michael Jordan. Orchestral music, and slow pans from hands and feet to face, are accompanied by the steady crescendo of a cheering crowd in the background. When Thackeray enters the courtroom, he is a gladiator entering mortal combat with India’s judicial system.

Intentionally or not, the film is perfectly reflective of Bal Thackeray’s hubris. All fascist rhetoric depends on bad-faith argumentation for its validity; here, Thackeray’s dialogues rely heavily on non-sequiturs, ad hominem, whataboutisms, and other rhetorical fallacies and tangential arguments that lead nowhere. Hardly surprising, considering the screenwriter is an active Shiv Sena member who employs the same gaslighting techniques in public debates and interviews. It’s also possible that Raut may consider his script to be unironically brilliant; after all, he believed that denying voting rights to Muslims would be a checkmate against “secularist hypocrisy.”

The movie switches between a modern-day Thackeray in court and flashback sequences of his rise to power during the 1960’s, as he progressed from political cartoonist for The Free Press Journal to fascist leader of Shiv Sena. The monochrome flashback sequences add a nostalgic, folksy aura. Despite the evolution implied by this juxtaposition of monochromatic flashbacks with present-day color sequences, Thackeray’s personality and rhetoric do not change at all. His “hero’s journey” is marked only by a continuous doubling-down on hate and resentment, gradually dragging his followers from Marathi populism into genocidal sociopathy.

From the first flashback to his days as a cartoonist, Thackeray developed deep feelings of cultural inferiority, conceiving of Marathis as frail and weak in comparison with the broad, muscular frames of Punjabis and Delhiites and the thick-boned ruggedness of Biharis in films and cartoons. He sees Marathis being outsmarted by the street-smart South Indians and Gujaratis who make up the majority of small business owners in the city. As I watched, I wasn’t really sure if Thackeray was hallucinating these grievances. What was familiar was the playbook of fascism, the manufactured defamation of whole cultures and peoples, ascribing to them villainous characteristics that don’t actually exist except in an aggrieved imagination.

The fire that ignites in Thackeray to build a system to help Marathi individuals find work in the face of “displacement” by “immigrants” from other states, speaks, at least in principle, to social populism. His support of workers’ unions, educational funding for the impoverished, and the construction of hospitals and medical support systems, all point towards broadly socialist goals. But because his ideas are fundamentally exclusionary, they’re twisted into the opposite direction of socialism. They aren’t meant to give Marathis an equal share of the pie, but on the contrary, to position them alone as entitled to the entire pie. In Thackeray’s vision, Maharashtra belongs to the Marathis alone, and all other residents are invaders.

Thackeray’s speeches in lecture halls to dozens and then thousands of Marathis, and his diatribes in his self-funded Marathi newspaper Marmik, adapt Hitler’s fear rhetoric on Jews to his own on Muslims. His politics become purely reactionary—it has no ethos of its own, and is predicated solely on a constant state of fear of the “other” and in preemptive retaliation for whatever the “other” may be feared to do. This allows right-wing fascists to be able to claim (false) victimization at all times. Their violence only exists as a “necessary” response to the imaginary violent intentions of the other side.

Much like with Hitler, whom Thackeray admired, tapping into a victim complex using blustering rhetoric was effective at gaining thousands of Marathi Hindu followers, and the steadfast support of loyal civilian soldiers for whom Thackeray would essentially act as Vito Corleone in The Godfather. Locals would come to Thackeray with complaints about Muslims and non-Marathis, hoping he would bully them into submission. Shiv Sena became Marathi folks’ own cosa nostra combined with a nationally powerful political and Hindu identity to help bend government to their whim. Bal Thackeray, their leader, became a celebrity and a deity.

Hinduism is ingrained at such a deep level in India that almost every facet of life, in some direct or indirect way, must display consciousness to the powers of a god. Shop owners keep small idols of Vishnu and Krishna in their stores with incense burning, rickshaw and taxi drivers have pictures of gods and gurus clamped to their visors, couples go on dates to scenic temples, and film producers title their movies based on auspicious number and letter patterns as dictated by their gurus and swamis. Ritualistic elements of Hinduism have become increasingly absurd in the modern context, and none more so than the transfer of idolatry from carved statues of the gods to politicians and movie stars.

Herein lies the grand paradox of Thackeray’s and Modi’s brand of Hindu nationalism. Much like the men who embody it, it is a hollow husk, with an underlying intention completely at odds with the cultural and spiritual tenets of the Hindu religion as conceived and developed thousands of years ago by meditating yogis. Hinduism in India today has been bastardized, co-opted, and mangled into a political identity of hatred and intolerance, much as the twisted, transparently un-Christian sects like the Prosperity Gospel of evangelical Christianity were co-opted into a political force by the far right in the United States.

Shiv Sena and the BJP created a branding of religious supremacy in order to compensate for the clear inadequacy that India feels on the global stage. Idolatry is now reserved for the political leader. Poojas, aartis, and religious ceremonies are for those who will advance the political agenda. Prayers and darshans will now be given for a BJP re-election. Moksha is dead, and salvation is found only in Modi, the man who sat idly by as Chief Minister of Gujarat while thousands of Muslims were raped and killed in the Gujarat pogrom in 2002.

It is clear from Thackeray that the exceptionalism of Marathi Hindus, especially those affiliated with Shiv Sena, is a puffed-up charade. There is nothing to distinguish Marathis above or below the rest of India’s ethnolinguistic cultures. There is also nothing exceptional about Hindus to distinguish them as above or below Muslims or Christians or Jews or Buddhists. Nationalism and fascism rely on the false and contradictory conflation of the supremacy of a race and/or religion, and the threat posed by some frightening “other.”

Hindus are a majority in India. Marathis are a majority in Maharashtra. There is no tangible threat to either identity that isn’t the result of right-wing ideological scapegoating of everything and anyone outside of themselves. Thackeray aches with a plea for the acceptance of Thackeray as a legend; a heroic myth of a man, memorable, witty, sharp, and astute; a celebratory figure of grand stature (he was 5’ 7”) who fought for a freedom previously denied to “his people.” When a lawyer accuses him of tearing down a mosque, Thackeray says the mosque was on the rightful birthplace of lord Rama. The lawyer says that there’s no proof of that. Thackeray responds, condescendingly, “where do you think he was born, Pakistan?” The crowd behind them laughs at Thackeray’s supposed wit. But the response is a non-sequitur, it makes no sense, and neither does the legend or celebrity of Thackeray. Hindu nationalism means never having to examine, but only to react, as quick and loud as possible.