I remember standing in the dingy hallway of a run-down coffeeshop across the road from Singapore’s Changi Prison, my phone wedged between my ear and my shoulder. In the vast compound on the other side of the road, a phone on the desk of some prison officer would be ringing, and I hoped that whoever picked up would be in a sharing mood.

It was 2016, and I was campaigning for the life of a death row inmate named Sarawakian Kho Jabing, convicted of murder after a botched robbery had resulted in the victim’s death. I’d met up with his family after their prison visit that day, and heard that another death row inmate might be scheduled to hang on the same day as Jabing.

And so I’d got on the phone to the prison, hoping to be able to verify that information. Relatives who come out of prison after visitating inmates often have news from “inside”; information based on what inmates say they’ve been told, or have managed to glean from gossip and overheard conversations. But such “intel” is often incomplete, and occasionally even erroneous, misinterpreted or misinformed. Verification is a challenge for activists like myself, who want to keep track of how capital punishment is applied in Singapore.

Someone picked up the phone. I introduced myself quickly, and got my questions out: “Is it true that there are two executions scheduled for this Friday?”

“I can’t tell you this sort of information over the phone,” came the reply.

“That’s no problem; I’m actually right across the road from Changi Prison. I can head over right now and you can tell me in person.”

“We can’t divulge this information to you.”

That was the end of the conversation. I never did confirm who that second person was.

Singapore, a tiny city-state with a relatively affluent and highly educated populace, is a staunch defender of capital punishment. It attributes its low crime rate to its tough “zero tolerance” approach, especially when it comes to illicit drugs. The majority of the inmates in Singapore’s prisons are behind bars for drug-related offences. So are the majority of those hanged under the law.

According to Singapore’s Misuse of Drugs Act, being found in possession of 15g of heroin, or 500g of cannabis, is enough for one to be presumed to be trafficking. If found guilty, the penalty is death, unless you fulfil specific criteria which would allow a judge to sentence you to life imprisonment, plus caning (judicial corporal punishment).

The People’s Action Party (PAP) government insists that this unforgiving policy is the key to the country’s security. “The death penalty comes within the context of trying to reduce the supply by making it clear to traffickers that if they get caught, they will face the death penalty. That substantially reduces the number of people who seek to traffic drugs into Singapore,” Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam claimed in a speech in 2017.

Yet, despite its supposed effectiveness as a deterrent, the death penalty in Singapore is kept carefully under wraps, hidden away from the public eye. Prison officers, counsellors, and medical staff who work with condemned prisoners and participate in executions—carried out by long-drop hanging—are bound to silence under the Official Secrets Act.

During Singapore’s Universal Periodic Review in 2011 (a regular review of the human rights record of each United Nations member), the government accepted recommendations to make information related to the use of the death penalty public, but this commitment hasn’t been fulfilled in any meaningful way. And because there is no freedom of information legislation in Singapore, citizens aren’t able to request such data directly from the authorities.

The only official data that we get about the death penalty is a single figure, included in the middle of the Singapore Prison Service’s annual report, of the number of executions conducted in the previous year. In 2018, that figure was 13—the highest that I’d ever seen it since I started working on this issue about a decade ago. Our own count, put together through piecemeal attempts to track executions, had put the number at eight or nine.

We still don’t know the identities of those we missed in our count. Society sees them as criminals and dealers of life-threatening substances, but the fact remains that these were human beings with names, histories, families. Their lives and deaths were made invisible by the state, even as the government insists that it’s all for the greater good.

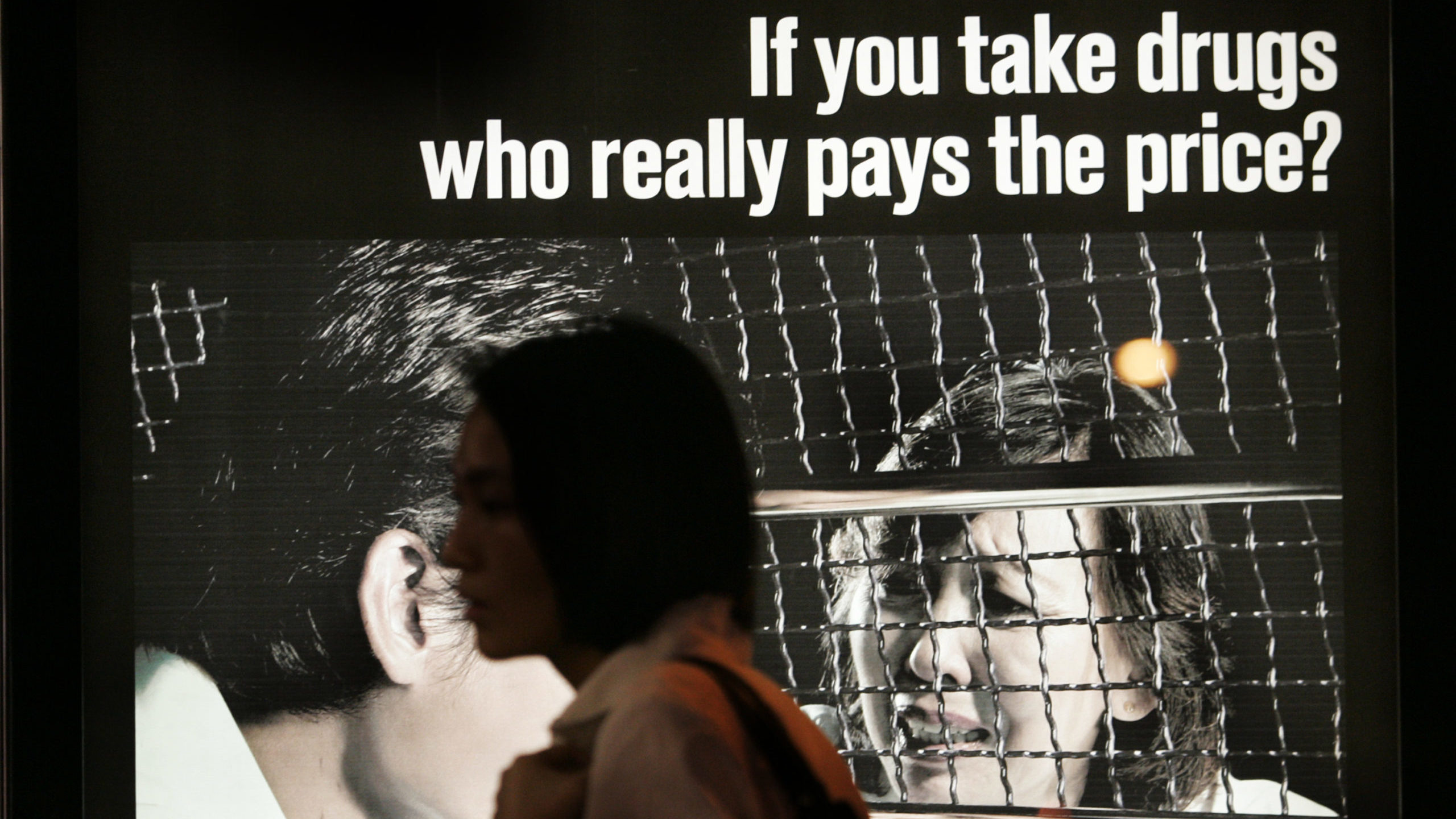

Visibility is important to a complex, sensitive issue like the death penalty. Offenders are easy to demonise, easy to write off, easy to forget. It’s important that the issue is made real to those who might never meet anyone who has had even a brush with the criminal justice system, much less faced the gallows.

I saw the power of this visibility in the very first death row case I got involved with. Yong Vui Kong had been arrested in 2007 with 47.27g of heroin at the age of 19, just a year over the minimum age for executions. He was sentenced under Singapore’s mandatory death penalty regime—which means that judges have no choice but to impose the death sentence upon conviction.

But Vui Kong wasn’t some unrepentant, hardened crime boss. He was a young man from a poor family with a history of domestic abuse, and who loved his mum, who was suffering from clinical depression. He’d fallen in with gangs after leaving Sabah for the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur as a teenager, treating them as his adopted family and doing whatever his “big brothers” told him to do.

After his conviction, though, Vui Kong resolved to turn things around. He became a devout Buddhist and a vegetarian, and studied hard. He taught himself to read and write Chinese, and started learning English and Malay. According to family members who visited him in prison, particularly his oldest brother and youngest sister, even the prison officers had commented that he was a changed man.

It was a compelling personal story that put a human face on an otherwise abstract issue. For human rights defenders and anti-death penalty activists, the priority was to save Vui Kong, but this was also a case that could raise public awareness of capital punishment and how it’s implemented in Singapore. It could make people take a long, hard look at the profile of people who find themselves on death row. Vui Kong’s experience highlighted that, while the main beneficiaries of the illicit trade are high-level drug lords, it tends to be low-level mules and couriers who pay the ultimate price.

We told Vui Kong’s story, over and over again, to anyone who would listen. We put out videos and articles. The Malaysian media, particularly the Chinese language press, interviewed his family, profiled him, and even published his letters as a weekly column. This exposure in the media was crucial in raising public awareness of Vui Kong’s case. It allowed people to get a sense of his journey, his reformation, and his remorse, making it harder for both the Singaporean and Malaysian governments to sweep things under the carpet.

In 2012, the PAP government tabled amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act that tweaked the mandatory death penalty regime: while judges used to have no choice but to hand down a death sentence upon conviction, the changes offered them an opportunity to choose between death and life imprisonment, with judicial corporal punishment (caning), if certain narrow criteria were met. When the amended laws, applied retroactively, came into effect, Vui Kong was found to fit the criteria, and finally escaped death row after the courts re-sentenced him to life imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane.

Things have changed in the decade since Vui Kong’s case. When letters written by Pannir Selvam, a Malaysian currently on death row in Singapore for trafficking 51.84g of heroin, appeared in the Malaysian press, Changi Prison claimed that he hadn’t written them. But his family and supporters point to scans of handwritten versions that had been uploaded to their campaign website even before the prison’s statement. When I sent follow-up questions to the prison, I received no reply.

I hadn’t been holding my breath; information about the death penalty has been getting harder and harder to obtain or keep track of.

Capital punishment in Singapore is thus kept distant and abstract, separate from the lives of the “ordinary Singaporean.” And since it’s out of sight and out of mind, the issue is overlooked in public discourse, treated as not urgent or important enough to be worth much thought.

A public opinion survey on the death penalty published by the National University of Singapore in 2018 found that 51% of respondents had low interest or concern about capital punishment, and 62% said that they knew little or nothing about the use of the death penalty in Singapore. A large majority of respondents couldn’t give even an estimated figure of the number of executions that had taken place over the past 10 years (between 2006–2015) that was within 50% either way of the actual number. Yet 71.9% of these respondents said that they were in favour of capital punishment.

This works in the authorities’ favour. With few Singaporeans scrutinising the use of the death penalty, politicians and officials are able to coast on the uninformed acquiescence of the populace. They’re left free to make claims about the utility of capital punishment even though researchers and experts have pointed out for years that there is no concrete evidence that the death penalty is more effective than any other punishment in deterring crime.

The lack of independent sources of information leaves the door open for the government to impose its own narratives, assumptions, and myths. This is clearly demonstrated by the YouTube channel of Singapore’s Central Narcotics Bureau, the police department in charge of tackling the illicit drug trade.

In the short film Last Days, the filmmakers imagine a future where drug policy reform advocates get their way and Singapore’s Parliament passes a law legalising drugs in the country. Within one minute of the video’s opening, a shifty-looking ethnic minority man in a hoodie stabs a young Chinese boy in the stomach in the middle of a supermarket aisle, and steals his tablet so it can be pawned for drug money.

The boy’s panicked father calls for an ambulance, but none are available. He thus has to run to the hospital with his bleeding son in his arms. Meanwhile, the drug addict is also making his way to the hospital, passing zombified people wasted in stairwells, and brushing off shady characters hawking black market drug paraphernalia.

At the hospital, the addict purchases an IV bag of some orange liquid, and goes into a ward meant just for drug consumption. As he hooks himself up to his substance of choice and relaxes back into his hospital bed, the desperate father is screaming for help as there aren’t enough beds for his seriously injured son. The parent sobs over his unconscious child parked in a bed in the hospital corridor; the addict drifts off to sleep, buoyed by his supply of narcotics.

“Countries around the world are taking steps towards decriminalisation and legalisation,” says text that appears onscreen. “Is this the world you want to live in?”

As videos go, it’s an astounding achievement of propaganda, painting an image of a society post-drug reform that’s designed to push every moral panic button there is. There’s no country where decriminalisation and legalisation has meant that urgently needed medical attention has been taken away from people because the hospital staff and facilities have been redirected towards facilitating highs. But that doesn’t matter in this video, because it isn’t interested in nuanced, deep discussions about policy change or harm reduction, measures that require careful thought and considered implementation.

Details regarding the death penalty and those facing it are severely restricted, while videos like this one are publicly available and openly distributed. Instead of informed, mature discourse, we get an asymmetry of information that feeds into biases, prejudices, and assumptions unsupported by evidence.

And so activists continue to struggle uphill on this issue, trying our best, on extremely limited resources, to combat the deficiency of data, information, and education.