After weeks of isolation at home, I went out to buy food. I spent a couple of hours trying to get everything I needed for a month, in order to reduce the outings as much as possible. The quarantine has not affected me drastically; I work from home and keep my mind busy most of the time. I often go for months with little contact with the outside world, but that does not mean I don’t worry about the possibilities, like a major food crisis in the most vulnerable regions of the planet. Venezuela is the fourth most acutely food insecure country in the world, with more than nine million people in danger.

I try to ration my intake of news; I like to be informed, but there are limits. Too much news can make one’s anxiety and fear increase exponentially. The habit of taking the news in doses, too, was one I’d already developed. It’s difficult to live in Venezuela, a country with such high rates of insecurity, crisis in the health system, product shortages, inflation, political prisoners, censorship, lack of water and so on.

A year ago, I lost my peace of mind for a long period, when the constant power failures and five-day blackouts disrupted my world: my work was interrupted, it seemed impossible to stay abreast of the reality, and the food was damaged in the refrigerator.

I felt nervous for a whole year. I changed my routines, I lived in a state of perennial worry; I bought less food to avoid losing it to blackouts; many times, I slept for a couple of hours, then woke up in the middle of the night to finish my work. The decrease in electrical problems had helped me to regain some calm before this new storm hit. The coronavirus arrived with fewer power failures, but the difficulties continue and in certain parts of the country the situation has become even more serious.

Water shortages are another common worry for Venezuelans. Many areas don’t have service every day, and during the quarantine there’s been still less water. Years ago, we had only to open the faucet, but gradually the problem has intensified. It’s easy to forget how lucky we are to be able to turn on a tap.

In the last few days, water stopped coming twice a week. I only got one day’s service, which makes the water tank just big enough to hold it; a few more days and I’m lost. Some places have had even worse service, they don’t receive water for weeks, how do they wash their hands at this time?

The streets looked emptier than usual when I went out for food. Everyone around me was also out buying food; everything else is closed.

Gasoline is another worry; the shortage has increased since quarantine began. A lot of people are worried about getting enough gas in their tanks for emergencies. Not everyone has the option of staying home. How will doctors get to hospitals? How will food be distributed if there is no gasoline in the country?

We have already experienced food shortages, but this too could be worse. In the last few months the economy in Venezuela appeared to improve because of the informal dollarization, a measure largely undertaken by the public to avoid the loss of value of their money. Since it is not official, the dollar circulates in the streets to a greater extent than the bolivar, but there is no possibility of saving, nor of paying the salaries of public employees, in dollars. We know that it is only a bubble, but it helped to give people a break. Now the stores have a greater supply, at least in food and certain products, although many medicines are still scarce.

So the concern in Venezuela extends far beyond the virus; nobody wants to get sick in a country where there are not enough hospital beds and the health system collapsed before the arrival of COVID-19. Venezuelans were already in the grip of a humanitarian crisis. What will happen when cases continue to increase? We were already anxious about the sociopolitical situation, inflation, shortages… What will happen in this country during and after the coronavirus?

Today I am grateful for having the ability to buy enough food for several weeks, such as fruits and vegetables—enough for the first few days—meats, cheeses, eggs, deli meats, sauces, spices, grains, flour, cereals, pasta, canned goods, and cleaning and personal hygiene products. I also included some cookies and ingredients for a cake, in these weeks it is good to have something sweet to snack on on hand. Many Venezuelans are obliged to expose themselves daily to buy only a few things. To live in a pandemic with only enough supplies for one day must not be easy.

I repeat a mantra: Esto también pasará, estaremos bien (This too shall pass, we will be fine). I see it everywhere, in social network posts, in videos, in articles… and it makes me remember to stay positive.

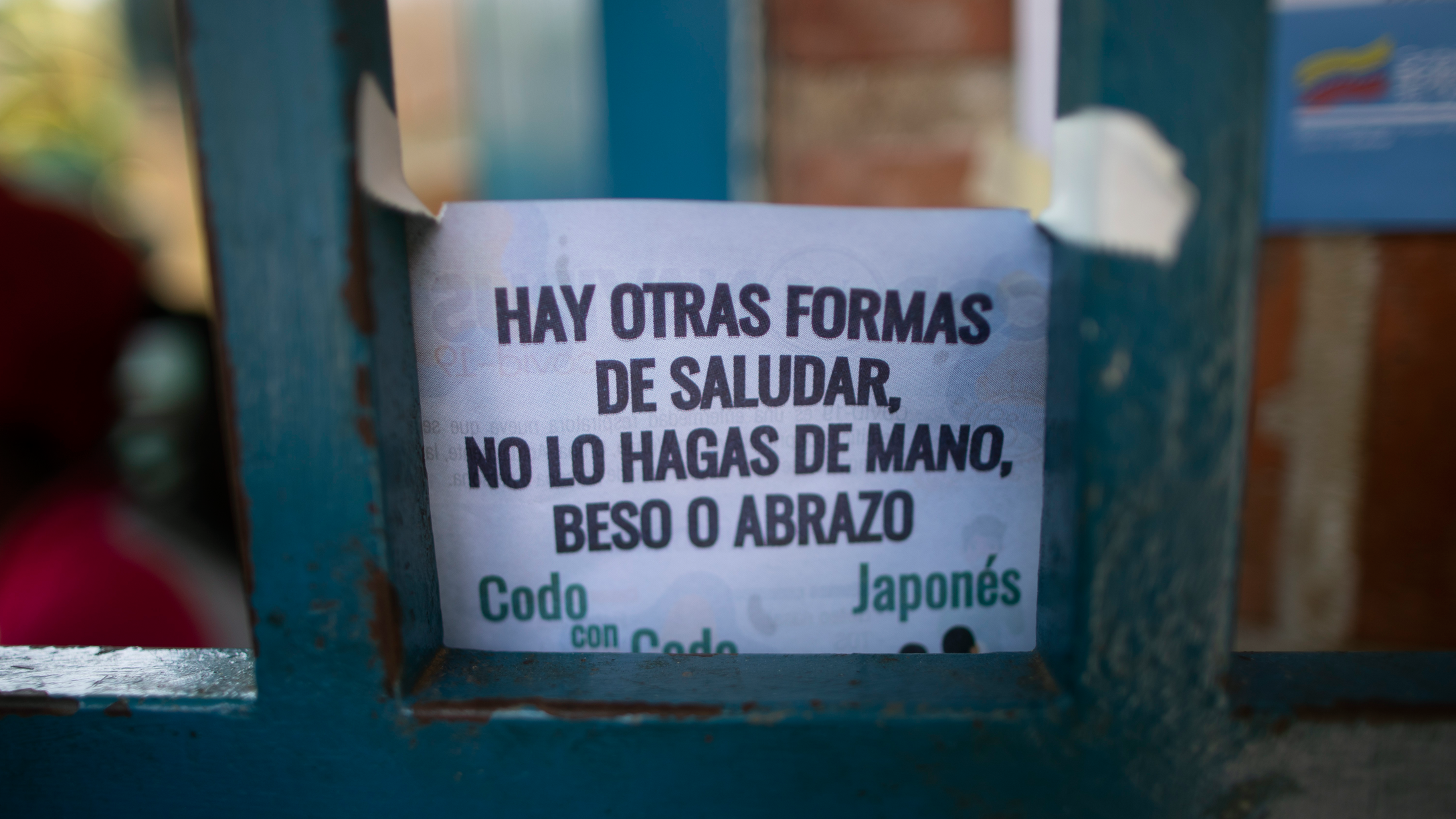

Outside, I focused on watching people, trying to be careful and not touch my face. We never pay attention to small details. How many of these people have placed their hands on a countertop? Are we maintaining an appropriate space between ourselves and other shoppers?

That’s how I spent my day, watching people of all ages make their purchases. There was someone who apparently had nobody at home to leave the baby with. The baby impacted me, and also the 3-year-old girl pushing a toy stroller next to her mother, who kept her eyes on her doll while breathing through a pink face mask—certainly cute, but a reality that shocked me back into the moment we’re living through.

Amid all the despair and uncertainty, I saw an 8-year-old boy with a face mask and a cardboard box. Inside he had two kittens, he wanted to find them a new home where they would be welcomed with love. This boy shouldn’t be on the street right now but he didn’t dump the kittens, instead he showed them kindness. I smiled for him and for all the people with hope, for all those who not only try to save themselves, but also help others, even if it is only in small ways.

screenshot: Instagram

screenshot: Instagram