I visited Europe for the first time at age 34, in late 2018. I had struggled through early recovery, but gritted out three months sober. I felt like I was growing, and felt that travel would support this. Of course, I had no plans to drink.

Yet on my first night in Madrid, after a party invitation from a kind stranger the alcohol and other substances came fast.

Cerveza. Polvos. Inhalantes.

At sunrise, I found myself on the street—alone, shaky, afraid.

Art hadn’t been a part of my life yet the impulse came to me to experience it, and for the next ten days, I poured myself into museums. At the Reina Sofia, I saw Guernica and its emotional turmoil made me feel whole again. I saw Pollock’s frenetic Brown and Silver I at the Museo Thyssen, and felt settled. The Sagrada Familia was massive, overwhelming, yet it comforted me.

I stayed sober. I came home changed. So began my foray into art.

For the next year, at home in New York City, I lost myself in the Met, MoMA, the Guggenheim. In every small gallery. In the design of the city itself, infinitely complex and forever changing.

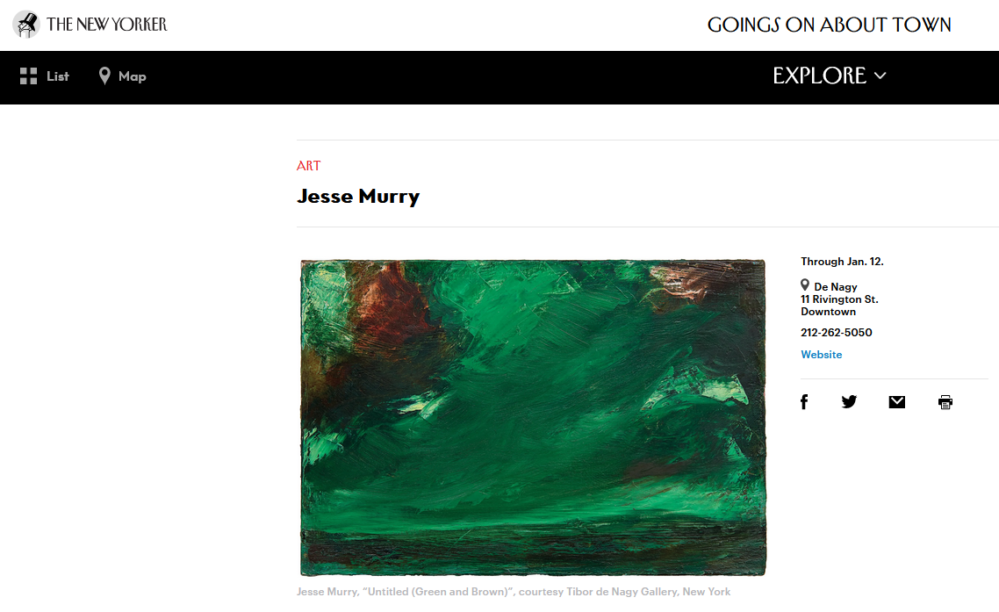

During this time I was thumbing through the New Yorker’s arts section when, in the notice of a gallery show, the small image of a canvas, a stormy splash of greens, roared off the page with Expressionist force. I didn’t know who Jesse Murry was, but his art—this tiny, two-dimensional reproduction—gripped me.

screenshot: newyorker.com

screenshot: newyorker.com

The next day I attended the exhibit, Radical Solitude, and it didn’t disappoint. Most of the colorful, sweeping works had a horizon: Murry’s focus as a fictional place for creativity and dreaming. Two paintings, Giant and the Giant of the Weather, and Middle Passage, trained a wide lens on mood, like a film’s tracking shot on a rolling sky, wistfully binding you to a limitless tension. Standing there, I felt in touch with something kindred. I was a man with an improved life—I had a year sober—but I still felt raw, still in my becoming. Murry’s works captured the essence of my situation: the rumbling and churning of outsized possibilities, if only I could make them so.

These works became a fixture in my life. I kept the gallery guide in a drawer with other keepsakes from my outings. On most days, I’d sit on the edge of my bed with the glossy booklet. Even for a moment, seeing the color storms grounded me or roused me or gave me a sense of connection. Eventually, I cut the images out and framed them. I wanted Murry’s work and its energy with me, over me always, like something religious.

I didn’t know why at the time. But whatever their totem-like power, this worked.

Even a couple of months later, when the pandemic started, any initial panic—like what I had experienced in Europe—seemed to slide right off. Not only was quarantine in effect, but my roommates were stuck across the country. I was alone, a scenario that while drinking or even in early sobriety would have triggered me. And yet I passed those days of early 2020 in solitude, with a growing sense of OK-ness. I sat patiently in the quiet, reading, talking to friends, or scouring online for art. I ran through Prospect Park as a near-daily ritual. I biked throughout Brooklyn, and though its streets and parks had been sapped of their normal teeming, I felt them come alive. I volunteered to support frontline workers. I didn’t drink. I felt a new self, sturdier, stabler, and more serene, taking shape.

And there were Murry’s prints—guiding, forging, and hinting at more to come.

As the first wave subsided, the city began to reopen. I had graduated from school years earlier, but the licensing exam had intimidated me. Now I sat for it, and passed.. Soon I found my first clinical job. Then, when my roommates moved out permanently, I took over the apartment’s lease—my first—and oversaw the renovation of the once-shabby space. I started dating, and I met the woman I would move in with in 2021.

When 2020 ebbed, and I had two years sober, I felt remade: not an improved version of my old self, but a new self altogether. The self Murry’s art had helped me imagine felt real. A good life—my own horizon—appeared here, now.

A second show, Rising, opened this past fall. These pieces were different: still based on the horizon, but closer to sunrises than stormy skies. They felt like openings, chasms of something, or revelations. For me, they couldn’t replace the earlier works. Not just artistically, but emotionally — those storms just meant too much to me. So much that I hadn’t even thought to learn more about their creator. Who was Jesse Murry, whose work had had such an abiding influence on me? Could learning about him tell me about my connection to his work?

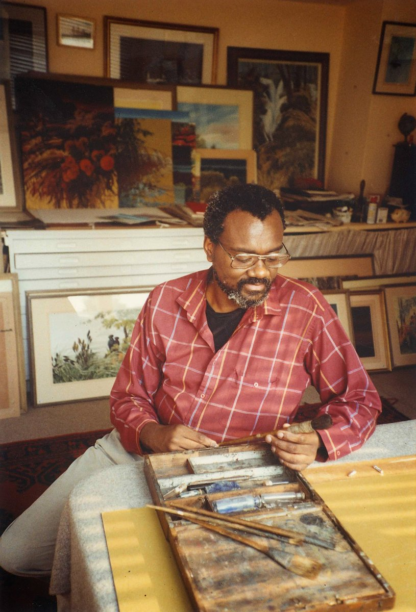

Murry was born in North Carolina, in 1948. According to writer Jarrett Earnest, his mother was talented, a musician, but also severely mentally ill and unable to care for him. He was sent to live with family down south, where he suffered both physical and sexual abuse. Eventually, he arrived in New York as an adolescent to live with an aunt. The parallels to my own life were striking. My mother had also been artistic, a dancer; both my parents were mentally unstable as well, one traumatized and erratic and the other depressed. Though I stayed home and didn’t experience any physical or sexual abuse, my parents were too consumed in their own financial and emotional unraveling to do the work of parenting.

As teenagers, it seems, Murry and I shared the common crisis of a traumatized identity, a bone-deep awareness of your own irrelevance. It’s not just confusing; it’s crippling. But where Murry had tools—resolve, insight, tenacity—I had none.

In New York, Murry haunted the local library and met Isabel Clark, the librarian who first guided him through the materials he would devour for his world-building. Eventually she became his legal guardian. As he prepared for college, she offered to send him to Europe, to find the places and things books had taught him. But in what Earnest called “a remarkable act of self-preservation,” he refused—he wanted psychotherapy.

Which was remarkable. For whatever Murry’s native gifts, he must still have been a terrified boy—abandoned and abused, Black and gay—who would, through his craft, strike out towards self-discovery. Murry was so young, so fragile, so damaged, and yet self-possessed enough to seek answers.

By contrast, I was an example of the worst of what childhood trauma does to people, which is to erase them, to reduce them to identitylessness. I hadn’t found books or art or tried in any meaningful way to find my niche in the world. I had no mentor, or even the most basic of life guidance. I plodded through the days. I didn’t preserve myself, but the opposite: I found alcohol, then drugs. When I did, finally, also find books and ideas, a larger world outside myself, at around 19, it was in many ways too late. I was too unskilled, too raw, too damaged. I tried to make a life for myself, and I failed. The years passed.

Murry’s life moved in two distinct directions, at once blossoming with creative genius, and winding towards a premature end.

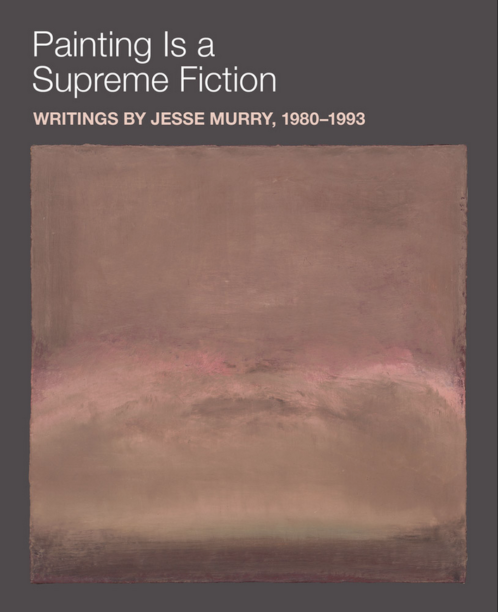

After college, he moved to New York City and became an educator, historian, and writer, producing art criticism that would be collected years later in a book, Painting Is a Supreme Fiction. But he felt frustrated. Why couldn’t he paint, as he could do other things? Already in his mid-thirties, he entered the MFA program at Yale. Here he found his artistic voice, melding the Romantic influences of John Constable and J. M. W. Turner with the poetry of Wallace Stevens — a personal triumph. But he also received his diagnosis as HIV positive. After his graduation in 1987, he returned to the City and painted the emotive works that would inspire others, including me, many years later. Jesse Murry died in 1993.

J.M.W. Turner, The Rape of Proserpine, 1839

When I started getting sober, I too was in my mid-thirties. Unlike Murry, however, nothing big or bold inspired me. After years of tumbling—through jobs, homes, faulty goals—I wound up down south, not far from where Murry was born. At the end of my substance use, in early 2017, I faced the condition of total loss that threatens many addicts: loneliness, joblessness, homelessness. I returned to New York desperate to save my life, if only I could get sober. I didn’t care about art. I wanted a job, a home, a sense of good health.

I just wanted to feel alive.

And today I do. I have three years sober now. My career is thriving. I’m writing. I’ll be married soon, and then a father, a chance to be the parent I never had.

I’ve wondered what role, exactly, art has played in all of this. I see Murry’s and my stories—of two men distanced in time and age, yet joined by experience and art—as the power of creativity, which means the power to become something other than what’s happened to you, other than your supposed fate.

In this way, the art serves as a means but not an end. You can just look at it and live in its beauty and emotive force forever, or hang it in your home. Except you can’t. Art is a fiction. It’s a way to cope, to feel the thrill of moving and breathing and thinking and feeling when real life saps you of these tiny joys. But this fiction can help you to learn to live.

I keep Murry’s prints in my work office now, where I treat recovering addicts. They help me stay calm on the worst of days, and they’re a pleasure to see in general. They’re mainly, however, for my patients, people in the throes of total loss. No one’s mentioned them yet. But I hope someday someone will notice.