I said goodbye to my brother, who wished me luck with eyes flooded with tears, then I left the house, followed by my mother. We took a cab to the airport.

Caracas-La Guaira is a long and dangerous road connecting the capital of Venezuela to the beaches, the northern cities and the exit door of the country, the international airport of Maiquetia. Some sections of the highway are completely dark, which always makes me nervous.

My flight was leaving in five hours, at 10 am. I fixed my eyes on the cerros parallel to the road. In daylight, they are a swarm of poor brick houses stuck to each other on the rough mountainside terrain, seeming to defy gravity as in a game of Jenga; when the sun sets they are transformed into an impressive reef of countless lights. In Caracas the starry night is not in the sky but in the mountains.

What do you pack in your suitcase when you leave your whole life, to start all over again in another corner of the world? I have only just obtained a journalism credential, in a country where I can put myself in danger if I talk about hungry children digging through garbage cans, or the $30 monthly salary that “should be enough” to meet basic human needs. My boyfriend in France told me to bring the most important things, but my family, including my cat, far exceeded luggage restrictions.

Venezuela is a low-key dictatorship; more than six million people have left the country in the current crisis, so the government does what it can to limit the continuing exodus. Metastatic corruption is an inescapable part of the Venezuelan lifestyle. Even if you have the means to emigrate legally, security functionaries will put you through a nightmare. We hear stories of would-be emigrants who were insufficiently careful about “disguising true travel intentions.” Authorities have shredded their documents, stolen from their suitcases, and forbidden them from leaving at all. So, like most who emigrate from Venezuela, I pretended I was just traveling for leisure.

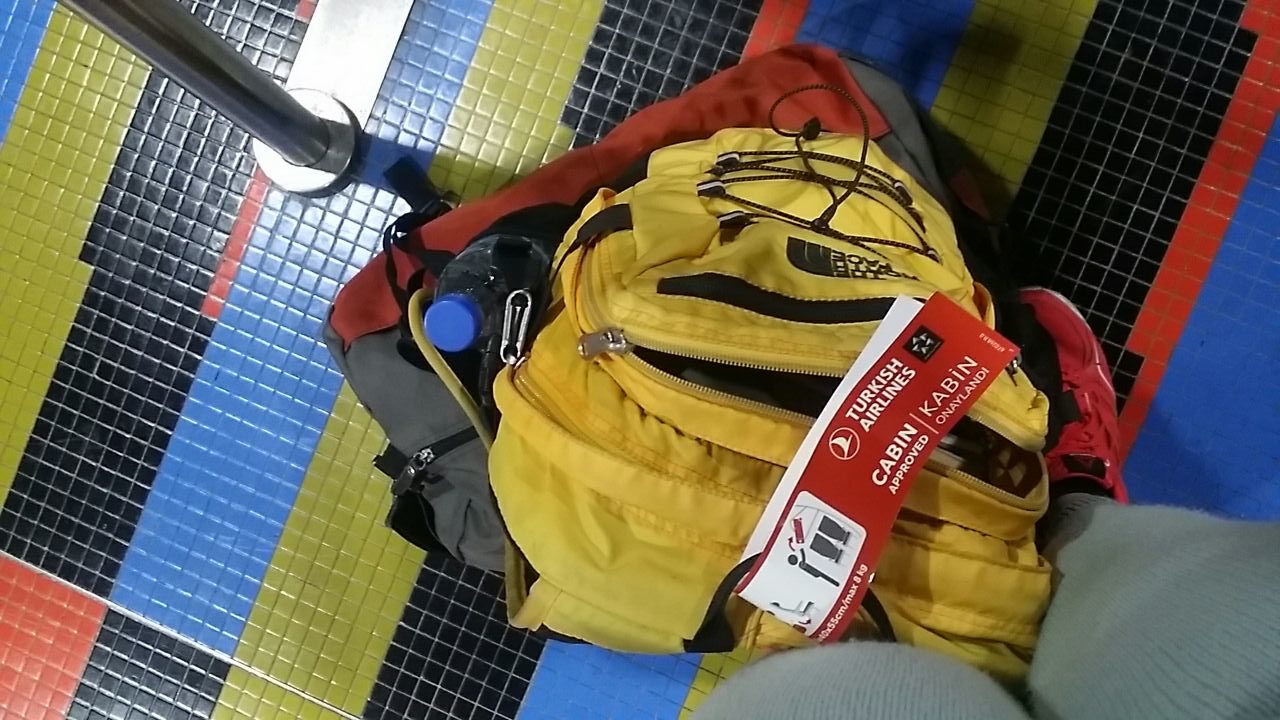

courtesy of the author

courtesy of the authorI had some legal documents pertaining to my forthcoming marriage in France, which I hid in my backpack, praying they wouldn’t be discovered.

Me voilà. Inside the airport, walking along the path of orange, blue, yellow, black and green tiles that make up an impressive display of kinetic art by the hand of Carlos Cruz Diez, the most famous mosaic in the country. I felt so small with my backpack and suitcase, hand in hand with my mom, who waited with me in the check-in line. At the Interpol control there were some suspicious officers interrogating people in the queue.

I had to face two military officers in red berets, one of whom looked just like Chavez with glasses. These guys have a reputation—the brutality of the gangs, mixed with the corruption of the police. My hands were shaking.

Chavez looked right into my eyes before commencing the interrogation. Everything was about to fuck up, I couldn’t be sure my voice would still be in my throat even to answer the first question.

“What is the reason for your trip?”

“Tourism,” I said unsteadily, repeating the word again just in case, but it sounded even worse.

“What will you do in France?” he asked, looking at me as if he found the sight of me distasteful. I focused on his red beret in an attempt to make him think I wasn’t afraid to look him in the eye.

“Tourism, tourism, I will visit friends.”

“Which friends?”

I knew it was over when he asked this, what kind of question was this? and then my Venezuelan impatience blossomed.

“Internet friends, people I’ve met online” I said steadily, shrugging.

“Who bought you the tickets?”

“My parents.”

“How much time will you spend abroad?”

“Three months.”

Chavez finished the ridiculous questions—questions that only immigration, and not the military, are supposed to ask me—and then he sent me to join the next queue. The check-in went amazingly, they put stickers on my luggage and gave me the tickets: Caracas – Istanbul and Istanbul – Paris (currently, Venezuela only has direct flights with Maduro-friendly countries, so most can only fly to Europe by stopping over in Turkey.)

I had less than five minutes to say goodbye to my mother before going to immigration. I remember her red eyes and her soft hand around the back of my neck. She blessed me, and then I lost sight of her for the last time. After that, everything happened in the blink of an eye.

Once aboard the plane, I watched a movie about a woman who lives in a caravan. I chose pasta over beef for lunch, everything moved very fast. Suddenly there were frozen scrambled eggs for breakfast. The landing lasted around 20 minutes. I discovered the immense and stunning airport of Istanbul, which looks like a futuristic city. The ceiling’s texture reminded me of the gills of a mushroom. I ran all over looking for the gate to my next flight, my shoulder hurt because of the weight of my luggage, I boarded again.

A Filipino man sat next to me during the flight. When he learned I am from Venezuela, his face changed to an expression of understanding my whole existence;, he laughed and said “Oh, you won’t be coming back to your country, will you?”, and winked at me. In the Paris airport, my South American body began to shiver at the unfamiliarly low temperature. I faced a policewoman at immigration, she was not nice but she was not Chavez, she sealed my passport. My now-husband was waiting for me in the airport hall, I ran toward him. I am free.

Although I am fascinated by the French Alps, la Tomme de chèvre, the lavender fields and the mountains of cigarettes in the rails of the trains, I am homesick. I secretly miss the noisy nights at my old quartier in Caracas, when most of my neighbors got along like druids in a ritual, to drink Polar Beer and eat cheap homemade burgers. I am still not sure when I will see my Venezuelan family again, or whether I will really

succeed in restarting my life far away from my homeland.