This story was originally published in The Fine Print.

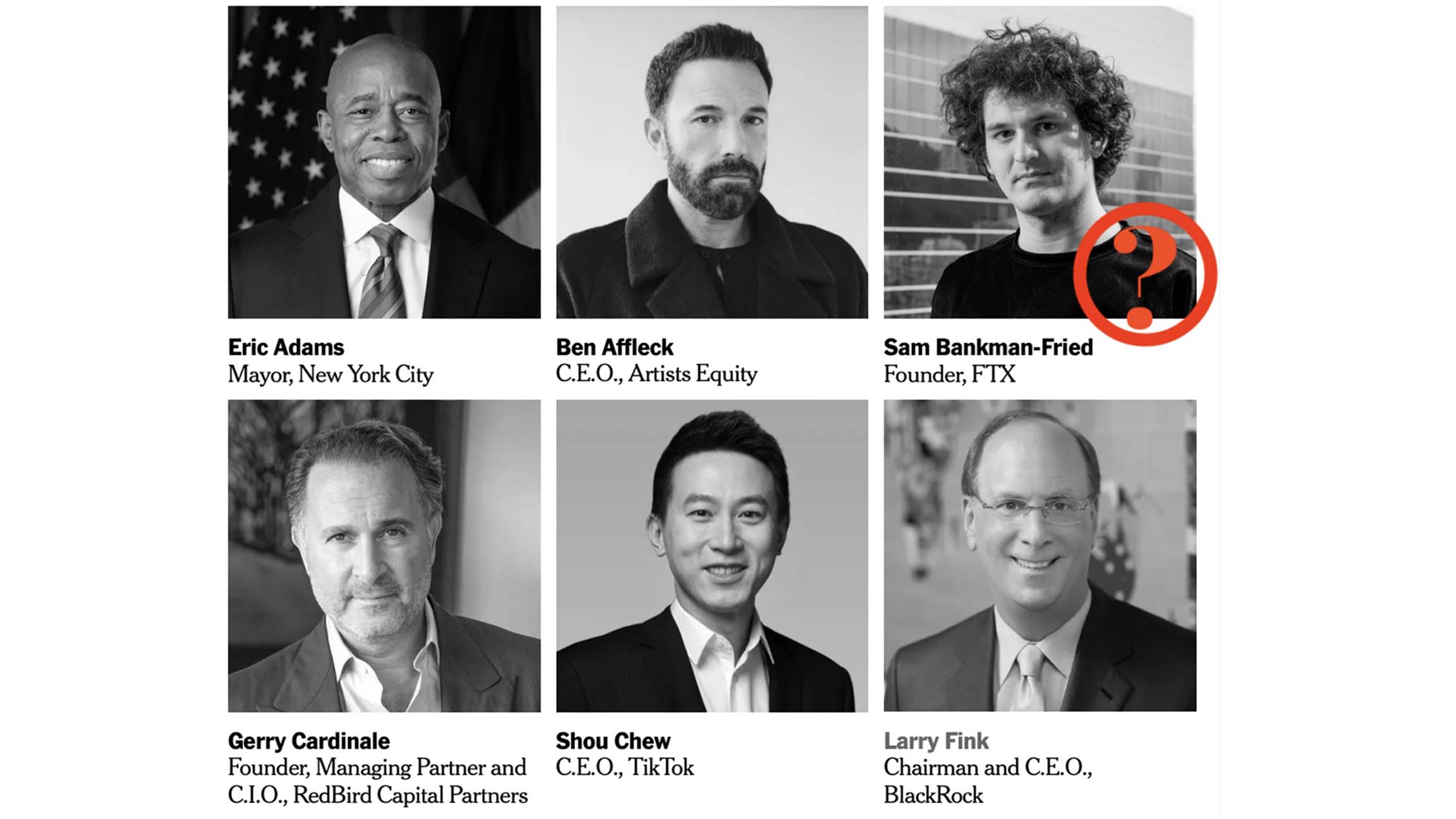

Last month, The New York Times’s DealBook newsletter promised that anyone willing to buy a $2,499 ticket for the 2022 DealBook Summit (if their application is accepted), to be held on November 30 at Lincoln Center, could take in “a series of conversations with the biggest newsmakers in the world of business, politics, and culture.” In the intervening weeks, one of the speakers on the announced lineup more than lived up to the promise of making big news: the cryptocurrency celebrity and FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried. Originally second-billed behind the likes of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky, and Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Bankman-Fried has become an object of fascination and derision after the FTX fiasco and ensuing bankruptcy evaporated what had recently been a $32 billion business and led to calls for his prosecution for fraud. Still, there is his headshot atop the grid of “today’s most vital minds,” standing out like Rumpelstiltskin trying to hide in a haystack.

According to a person familiar with the situation, Bankman-Fried remains an invited speaker. The Times has been in touch with him in the last week, and he hasn’t canceled yet. As with other outlets that have noticed him on the DealBook Summit roster, The Times declined to comment about whether Bankman-Fried would show up to The Fine Print. And there are signs that DealBook Summit organizers have been keeping an eye on the circumstances surrounding their news-making invitee: Internet Archive captures show that sometime on November 17, his bio page stopped describing him as the CEO of FTX. (Since the company filed for bankruptcy on November 11, John Ray III, who served as CEO after Enron collapsed, has been serving in that role; “Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls,” he wrote in his first legal filing.)

In the weeks following the failure of FTX, which watched its $32 billion valuation evaporate in a matter of days, Bankman-Fried has, in the popular imagination at least, joined a roster of financial villains like Bernie Madoff, Elizabeth Holmes, and Enron’s Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling. It’s unclear whether Bankman-Fried will face criminal charges — though the FTX collapse is currently under investigation by the U.S Department of Justice, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, and the Financial Crimes Investigation Branch of the Royal Bahamas Police, , which has jurisdiction over the company’s legal headquarters. Times spokesperson Naseem Amini did make one thing clear to The Fine Print: If Bankman-Fried shows up (or, like Zelensky, appears via Zoom), he won’t receive a speaking fee. “Our events are live journalism,” Amini said. “We don’t pay interviewees.”

As journalism goes, few outlets would turn down a Bankman-Fried interview at the moment. But staging live events has put news outlets like The Times in the ticket promotion business that’s more akin to the line of carnival barkers than reporters and involves significantly more touting of its participants — at least in the marketing materials — than would be expected in the pages of The Times itself. Announcing last year’s DealBook Summit, Andrew Ross Sorkin spared no superlatives about the people who had agreed to come. “Every year, we bring together the most consequential people in the world for thoughtful, in-depth conversations,” Sorkin was quoted in the press release. “This year’s group is at the center of some of the most important shifts, from technology and health to climate change, inequality, and democracy.”

Bankman-Fried wouldn’t be the first controversial figure featured at a DealBook Summit. In 2021, Adam Neumann gave his first interview since stepping down as WeWork’s CEO two years earlier to Sorkin at the Summit. “You were kind enough about two years ago to invite me to speak in the midst of everything, and you gave me the opportunity and said that it would be a great stage,” Neumann said then. “When I stepped down, I took a moment just to reflect, and it was very quickly apparent that any word I would say, anything I would do is just going to attract more attention to me. And because it’s always been about the company first, I made a very conscious decision not to speak.” In the interview, Sorkin pressed Neumann repeatedly on how he could walk away with as much money as he did despite the cloud over his exit.

Unlike Neumann, who stayed out of public view before he showed up at the DealBook Summit, the value of a Bankman-Fried interview has been undercut slightly by just how much he’s already been talking to the media. “He’s talking when other people wouldn’t,” Chase Peterson-Withorn, who wrote a cover story on Bankman-Fried for Forbes before the FTX edifice collapsed, told Vanity Fair’s Charlotte Klein. Earlier this month, Times business reporter David Yaffe-Bellany landed the most extensive interview yet with the fallen crypto king, though the resulting piece led to complaints that The Times treated a suspected fraudster too credulously. When Yaffe-Bellany asked about some cryptic tweets by Bankman-Fried, he answered, “It’s going to be more than one word. … I’m making it up as I go.” Some speculated that this answer was misleading and that his true motive for the tweets was a ploy to avoid being detected deleting old tweets, though others have called that theory debunked. Two days later, Bankman-Fried DM’ed Vox Future Perfect senior writer Kelsey Piper: “Fuck regulators” and “I feel bad for those who get fucked by it … by this dumb game we woke westerners play where we say all the right shiboleths [sic] and so everyone likes us.” Though he later claimed he did not know the chat was on the record: “Last night I talked to a friend of mine,” he tweeted. “They published my messages. Those were not intended to be public, but I guess they are now.”

The adulation Bankman-Fried received in the business press as a financial and moral messiah during FTX’s run-up has caused some to reconsider their past coverage as lacking the kind of skepticism usually expected of journalists. “Like any good con man, SBF told us a story we wanted to hear and were eager to believe,” Jeff John Roberts, who wrote a Fortune cover story on Bankman-Fried, wrote recently. “It was all bullshit, of course, and I didn’t see through it.” However, not all involved share his regrets. Fortune’s editor-in-chief Alyson Shontell, who The Fine Print has previously reported has a history of editing stories to be more positive about the wealthy and powerful, wrote in a newsletter that she stood behind her magazine’s coverage of him. “So, did SBF belong on our August cover? I’d say yes, unequivocally,” she wrote. “I’m proud that we had the foresight to capture SBF at his peak.”

The Times does not break out its live events revenue in its financial reports, lumping it into an “Other” category that includes Wirecutter affiliate referral revenue, licensing, television and film fees, subleasing its office building, retail commerce, and commercial printing at its plants. But you can get a sense of scale of what live events generate from its 2021 annual report: It reported $215 million in its “Other” category, and if you back out the sub-categories it did report, it leaves $80.9 million from live events, commercial printing, and retail commerce.

DealBook, which started in 2001 as a newsletter sent by Sorkin when he was a young reporter on the business desk, has become a venerable franchise for The Times. But it’s long had a somewhat complicated relationship with the business desk. Sorkin, who has been with The Times since he talked his way into an internship during his senior year in the class of 1995 at Scarsdale High School, has often clashed with Timesian norms. As Gabriel Sherman wrote in a 2009 New York magazine profile, “He’s not a Timesman, exactly. He’s his own creation, and he doesn’t genuflect to Times traditions.” The piece spelled out concerns some of his colleagues at the paper had about what they regarded as Sorkin’s close and too-credulous relationships he had developed with the powerful people he was supposed to report on. One veteran insider compared Sorkin’s reporting to Judy Miller, a reporter whose close relationships with Bush Administration officials led to bogus intelligence claims appearing in The Times while it was building support for launching the Iraq War. “She got too close to her sources,” the source told Sherman. “It was disastrously wrong, and we let our readers down. This is the financial equivalent of that.”

As the avatar of the DealBook franchise — there are also DealBook DC events, and lately, seven other reporters typically share the byline with Sorkin on the newsletter — Sorkin gained a reputation for an entrepreneurial mindset and has pitched many business ideas. “Maybe it was uncouth, but I was always the guy who was pushing these plans and prospects on people,” Sorkin told New York. “I’ve had so many cockamamy ideas I would love to have been able to do.” Since 2011, he’s also elevated his public profile by becoming a co-host of CNBC’s Squawk Box. The 2009 profile reported he was receiving a $250,000 salary as well as a “bonus” based on the DealBook franchise’s performance, ranking him “among the highest-paid staffers at the paper.” Sorkin disputed those figures at the time and did not respond to The Fine Print’s request for comment for this story.

These days, the DealBook Summit can put the tensions between guest booking and reporting on display. Over the last weekend, two new speakers were added to this year’s event: Ben Affleck, credited as CEO of Artists Equity, and Gerry Cardinale, the founder of managing partner RedBird Capital Partners. On Sunday, the first announcement of Artists Equity, a film production company Affleck is starting with Matt Damon, appeared as an exclusive by Times entertainment business reporter Brooks Barnes. And as it turns out, backing the new venture with “a minimum of $100 million in financing” is RedBird. The close timing of the announcement and their addition to the speakers’ list suggests the possibility of coordination. But a Timesspokesperson denied any quid pro quo. “When Brooks Barnes started reporting on Matt Damon and Ben Affleck’s new film production company, he knew nothing about Affleck possibly talking at the Summit,” Amini said. “One had nothing to do with the other.” Barnes backed up that account. “By the time I found out that Affleck was participating in the summit, the reporting was mostly done,” he told The Fine Print. “I didn’t know Cardinale had also joined until this very moment!”