ON NOVEMBER 16, Yale Law School, the current No. 1 entry in U.S. News’ ranking of the nation’s top law schools, announced it would no longer participate in the making of future editions of the rankings. Harvard Law, U.S. News’ No. 4 school, immediately did the same.

For decades, the U.S. News rankings have had near-absolute, definitional control over law schools’ reputations, dominating every aspect of law-school administration as schools contort their policies to try to fit the U.S. News scoring criteria. The pecking order for student matriculation, professor employment, and journal publication is, essentially, whatever U.S. News said it was in the most recent edition. The rankings of various educational and other institutions also consumed the actual publication U.S. News & World Report, until it ceased to exist as anything but a rankings-production company.

(Disclosure: my wife teaches at a historically illustrious but relatively under-ranked law school.)

But Yale and Harvard are in the small number of law schools whose statuses (namely: Yale Law the undisputed most elite, with Harvard Law somewhere close behind) exist securely outside the U.S. News charts—and whose withdrawal, therefore, threatens the whole concept of the rankings, and offers less powerful schools a chance to escape the system. Ten more schools have since followed their lead, ranging from No. 2 Stanford to the law schools at the University of California’s Irvine and Davis campuses, tied for No. 37.

With more than half of U.S. News’ ruling Top 14 tier renouncing the rankings, a sort of reverse-prestige competition has kicked in. Why can’t the remaining schools let go? The University of Chicago, at No. 3, has its own brand commitment to reactionary contrarianism (or, as the dean framed it in an anti-non-participation statement, to “the free expression of ideas”) to uphold. The others—Penn, NYU, and Virginia, tellingly clustered at 6, 7, and 8 respectively, and Cornell at No. 12—well, who would know they’re right behind Columbia, or just ahead of Northwestern, if the rankings weren’t there to say so? With U.S. News saying it’s going to keep ranking the schools whether the schools provide validated data to them or not, dropping out means losing what control they have over their standing.

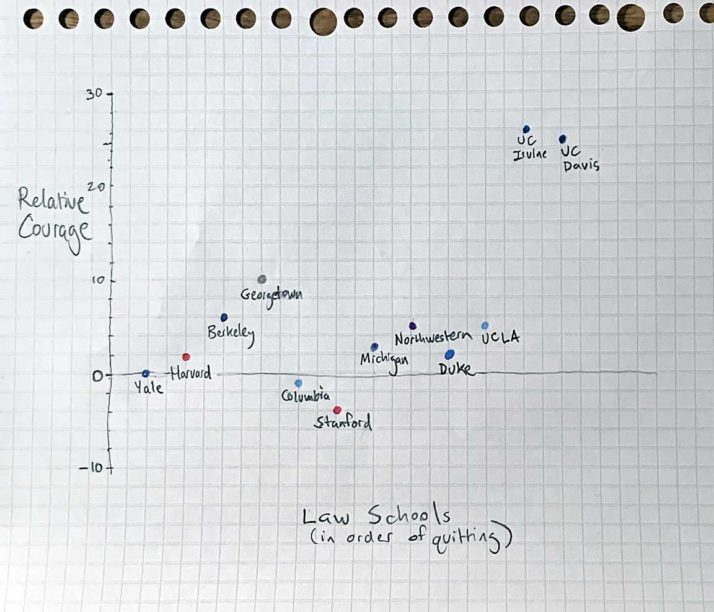

Rather than dwelling on institutional cowardice, though, let’s analyze institutional courage. Yale Law could afford to be the first to quit, because it was first on the list. But Berkeley was the third school to jump, despite being only No. 9. And Georgetown went right behind it, showing impressively little concern about its No. 14 ranking, and leaving the likes of No. 4 Columbia and No. 2 Stanford scrambling to catch up.

So the question is, how quickly did a school act, relative to how much it stood to lose? I listed the 12 law schools in order of when they announced they were quitting the rankings, then subtracted each law school’s position on that list from its position on the U.S. News list. Yale, No. 1 on both, established a baseline courage score of zero. Georgetown, No. 4 to quit and No. 14 on in the rankings, got a score of 10; Stanford, No. 6 to quit and No. 2 on the rankings, scored -4.

Here’s the resulting chart of the dropouts’ performances:

Correction: This post originally listed the Penn–NYU-Virginia bloc as 7 through 9 in the U.S. News rankings; they are 6 through 8, respectively.

Thank you for reading POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!