When I was in standard four, my primary school hired a French teacher. He was from West or Central Africa, used a lot of cologne, wore very tight trousers, and took at least 3 smoke breaks during our 35-minute classes. He taught us the word “moi.”

Moi (me) was such a simple word, such an elementary word, such a basic word, and such a dangerous word. In Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi’s Kenya, moi named the intimacy between tyrant and student, the identification between tyrant and student.

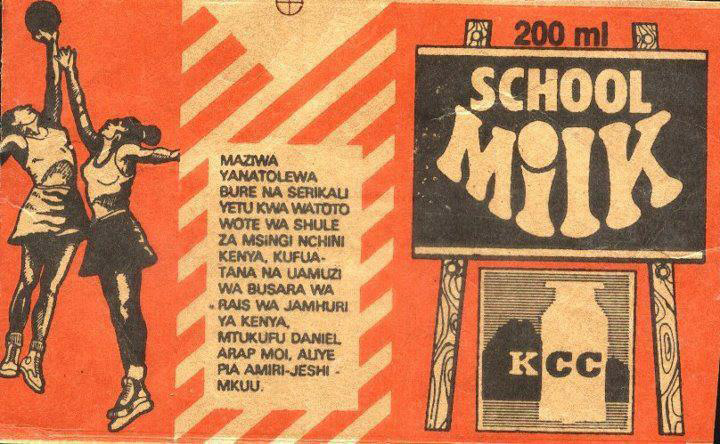

I am trying to capture, here, what it felt like to be a child growing up under Moi in the 1980s. Moi was, in a very real way, me. Moi was everywhere. He was the beginning sentence of every news broadcast. He was the closing benediction to every prayer. He was the subject of every major headline. He was the face you met on every business wall. He was the flavor of the free milk provided to primary school children. He was our Freudian father. He was the name of the avenue that led from my primary school to the center of Nairobi. He was our sustained, inevitable, object of attention. Perhaps of affection.

I attended Nairobi Primary School, about a kilometer from State House, the president’s official residence. State House is surrounded by schools: Nairobi Primary, State House Girls Secondary, St. George’s Primary, and State House Primary. When foreign dignitaries visited State House, we would be pulled out of class, handed paper flags, lined up along the road leading to State House, and instructed to cheer. We cheered. How we cheered.

I would like to say that we cheered because we were happy to be out of stuffy classrooms, glad to be liberated from double maths or double geography or double history or double home economics, or whatever post-lunch subjects our schools had lined up. I would like to claim that we cheered less because we loved Moi and more because we were excited to be among other students from other schools. That it was all about peer pressure and state demand. I would like to claim that we jeered, instead of cheered.

But I can’t. Propaganda works on the young. Our sentences started and ended with him. Our prayers started and ended with him. “I pledge my loyalty, to the president and the republic of Kenya,” every Friday morning. We were told to call him “Baba.” How could we not love him? How could I not love him?

We drank his milk every break time. We knew break time was close because we would hear lorries delivering milk to the school and then the slap of a plastic crate outside the classrooms, a daily present from Baba Moi, our father president. The milk was cold, perhaps it had been refrigerated, and we tore the packets open with our teeth, and were supposed to guzzle it together. It was a communal exercise: across Kenya, primary school children drank free milk provided by Moi every break time. When, later, I encountered T.S. Eliot’s line about measuring life in coffee spoons, I grasped it because we had measured our school lives in milk breaks.

Loving Moi was complicated.

I was a child of professional Kikuyu parents, the products of Alliance Girls, Makerere University, and University of Nairobi, elite schools that were created to produce and reproduce an African elite. They were children of war: my father was born in 1939, my mother in 1945, and both lived through Kenya’s war for independence in the 1950s. My mother’s father, a teacher, was arrested by the colonial government in 1952 and released in 1960. My mother says that a day after my grandfather was arrested, the colonial government arrived with bulldozers and destroyed his stone house, displacing and dispossessing my mother, her mother, her stepmother, and all the siblings. From prison, he wrote letters that insisted his children must be educated. As with freedom fighters across Africa and Afro-diaspora, he understood that education was key to freedom.

But education was about more than just freedom. As an educated man, he had built a stone house at a time when most Kikuyu lived in huts of wood, straw, and mud. Education was a way to build wealth. And when independence arrived in 1963, it was time to build and rebuild wealth.

Jomo Kenyatta’s Kenya was built to cater to the professional Kikuyu class. If you had attended high school, preferably somewhere elite like Alliance, but any good high school would do; if you had attended university, Makerere in Uganda or Dar es Salaam in Tanzania or any of the airlift schools in the U.S. or Germany; if you belonged to any of the professional occupations— doctors, lawyers, engineers, architects, mostly for men, and nurses, teachers, secretaries, almost exclusively for women; if this was you, then Kenya was built for you. You were the subject of state planning. You were addressed and catered to in official state documents.

When Kenyatta died in 1978 and Moi took over, it was a crisis. Moi wasn’t, and had not: He wasn’t Alliance; he wasn’t Makerere; he wasn’t Tom Mboya Airlift. Unlike Kenyatta, he had not studied at the London School of Economics under Bronislaw Malinowski and written a book, Facing Mount Kenya.

Kenyatta used detention without trial against radicals, but Moi’s repression did not serve the Kikuyu professional class. Moi impeded promotions. So and so, from Alliance and Makerere, should have had that prestigious job. So and so, a doctor and part of the Tom Mboya airlift, should have been able to buy a bigger house. So and so, a lecturer with a PhD, should have been able to travel abroad for a conference. His real acts of political repression combined with ethnonational snobbery: Moi was hiring “uneducated” people from his “tribe,” those who lacked Alliance, Makerere, Airlift. On and on.

Stray comments gathered over many years. Perhaps, with your closest Kikuyu friends, in a private residence, you could discuss Moi. But you had to be careful. In public, Moi was discussed in whispers. Squeezed-together bodies. Alert eyes looking for listeners. There was a choreography to discussing Moi. Move close. Lower your voice. Say just enough. Move on. Today, we might call these whisper networks.

A child observes, but is not privy to the whispers.

I understood Moi was bad: he had not gone to Alliance. He had not gone to Makerere. He was not Tom Mboya Airlift. There were whispers that he worshipped the devil. There were whispers that major tragedies happened right before he visited a place, because he was sacrificing humans to the devil. There were whispers.

But I saw that he went to church every Sunday. It was on TV. The Sunday news would start, “Today, His Excellency Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi attended x church.” And I saw that the churches welcomed him and his donations and his prestige and they loved to say he was a Christian. I was a Christian; were we the same kind of Christian?

If Moi punished people, as it was whispered he did in the basement of certain buildings in the middle of Nairobi, surely fathers had the right to punish disobedient children. He was, after all, a “God-Fearing Man.” The evangelical and pentecostal preachers I loved told us that Moi was a good man. He was Christian. Like us.

If now, having read the Report of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission; having read S. Abdi Sheikh’s Blood on the Runway, a narrative about the 1984 Wagalla massacre; having read Maina wa Kinyatti’s Kenya: A Prison Notebook; having read Shailja Patel and Joyce Nyairo and Grace Musila and Wambui Mwangi about life under Moi; if now, I can narrate a different story, a story that makes sense of the stories I knew and didn’t know, the whispers that circulated but were never loud enough to reach me, that reconstruction does little to address how I felt about Moi.

I knew I was supposed to hate Moi. I don’t know that I did.

By standard four, I had tried to stop drinking the free milk. I would throw it in the trash. An act of rebellion. Perhaps. It was cold and I found it unpleasant. Perhaps I had absorbed the whispers around me that Moi—and, by extension, his milk—was toxic to the Kikuyu professional class. Perhaps the bitterness with which he was spoken had tutored my tastebuds to experience him and his products as bitter. I was not alone. Several other students tried to stop drinking the milk and would throw it in the trash bins or dump it into the school toilets. The school responded by making it mandatory for us to drink the milk at our desks, watched by the teachers. Another prison. By standard six, I had stopped singing the national anthem. I would mouth the words, or stay silent, as long as I was hidden in the crowd. By standard eight, I had stopped reciting the pledge of loyalty. As long as I was in a crowd.

Perhaps I understood something about habit and discipline. Perhaps I simply liked not doing what I was supposed to do. Would I name these acts of resistance? I don’t think so. At best, they were ways of inhabiting the contradictory ways I felt about Baba Moi. The cruel father. The everywhere father. The father I hated. The father I loved.

I have wondered if I should forgive the child I was for not recognizing the tyranny he inhabited and swallowed day after day. I have wondered if I should forgive the child who assembled a world out of scraps and whispers, paranoid glances and defensive body vernaculars. I have wondered if I should forgive the child I was for not knowing how to direct love and hatred, suspicion and gratitude.

How do I say to him that he might have navigated the fractures of that world differently?

From this distance, with official reports and extended study in hand, it is easy for me to claim I always disliked Moi, that I rejected his milk because of what I knew and felt as a child. From this distance, it is easy to disavow the identification created by reciting the loyalty pledge every Friday, and cheering for him along State House Road. From this distance, I want to tell a story that paints my childhood as less politically naive, as more discerning. Do I dare be honest?

Had I been invited, I would have recited poetry for Moi. I would have donned a sisal skirt and performed any of the many songs created to flatter and appease him. In his presence, I would have recited the pledge of loyalty with heart. I would have been sincere. Because I loved my father.

Perhaps I needed to learn moi, in French, to find a different way to bend my tongue and brain, to escape from the universe of Moi. If I identified with Moi, I also found, in a foreign tongue, a way to manage the dissonance between school and home, between a sycophantic state and a resentful Kikuyu professional class. And, perhaps, I recall that teacher’s numerous smoke breaks because they were different kinds of breaks, unsanctioned breaks, breaks that had nothing to do with drinking Moi’s milk and being part of whatever collective emerged as primary school children across the country participated in that ritual.