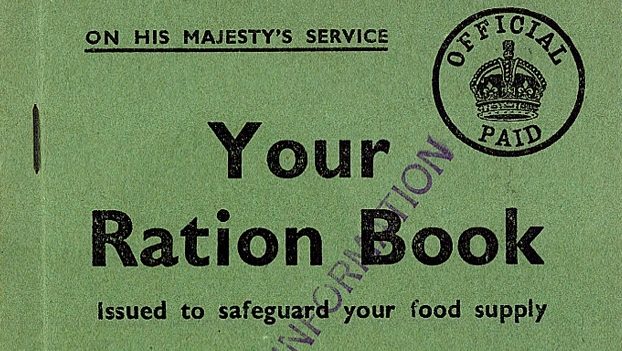

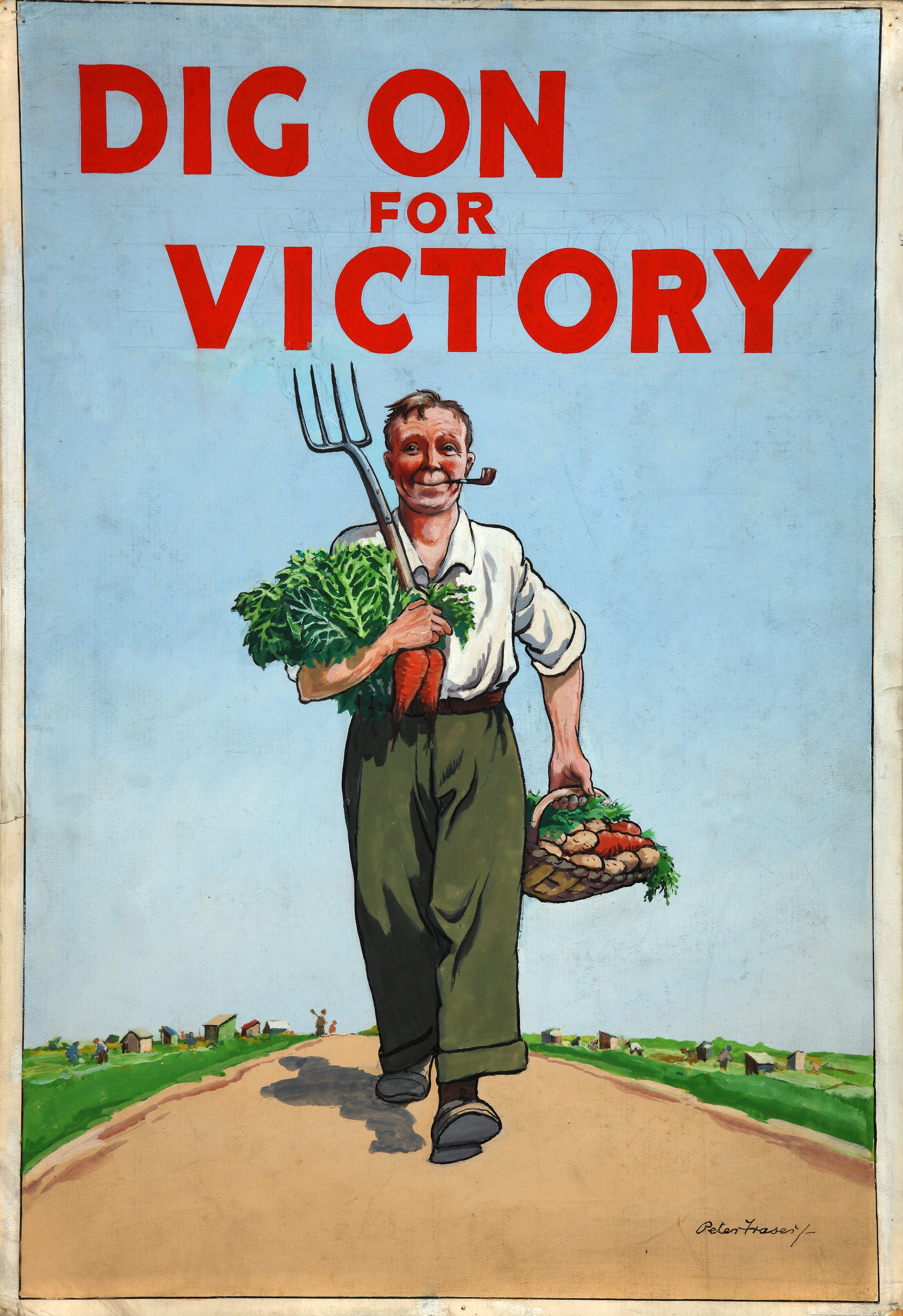

The Ministry of Fear, a Graham Greene novel published in 1943, begins at a church fete, where the main attraction is a fruit cake which you can win by guessing its weight. England during WWII found itself alarmingly short of food, because the ships on which supplies depended kept getting torpedoed by German U-boats. The Brits were encouraged to Keep Calm and Carry On, and also to plow up their precious lawns into vegetable gardens in a Dig For Victory campaign. Things like sugar, eggs and butter were rationed – a state of austerity which continued for some time even after the end of the war (with food rationing not completely abolished until 1954). Hence the starring role in Greene’s novel of the fruitcake, full of sugar, butter and eggs, to a half-starved populace the very stuff that dreams are made of. (Other novels written in Britain during WWII similarly dwell nostalgically on the comparative ease and sensuousness of pre-War life, Brideshead Revisited being a memorable example).

NATIONAL ARCHIVES UK

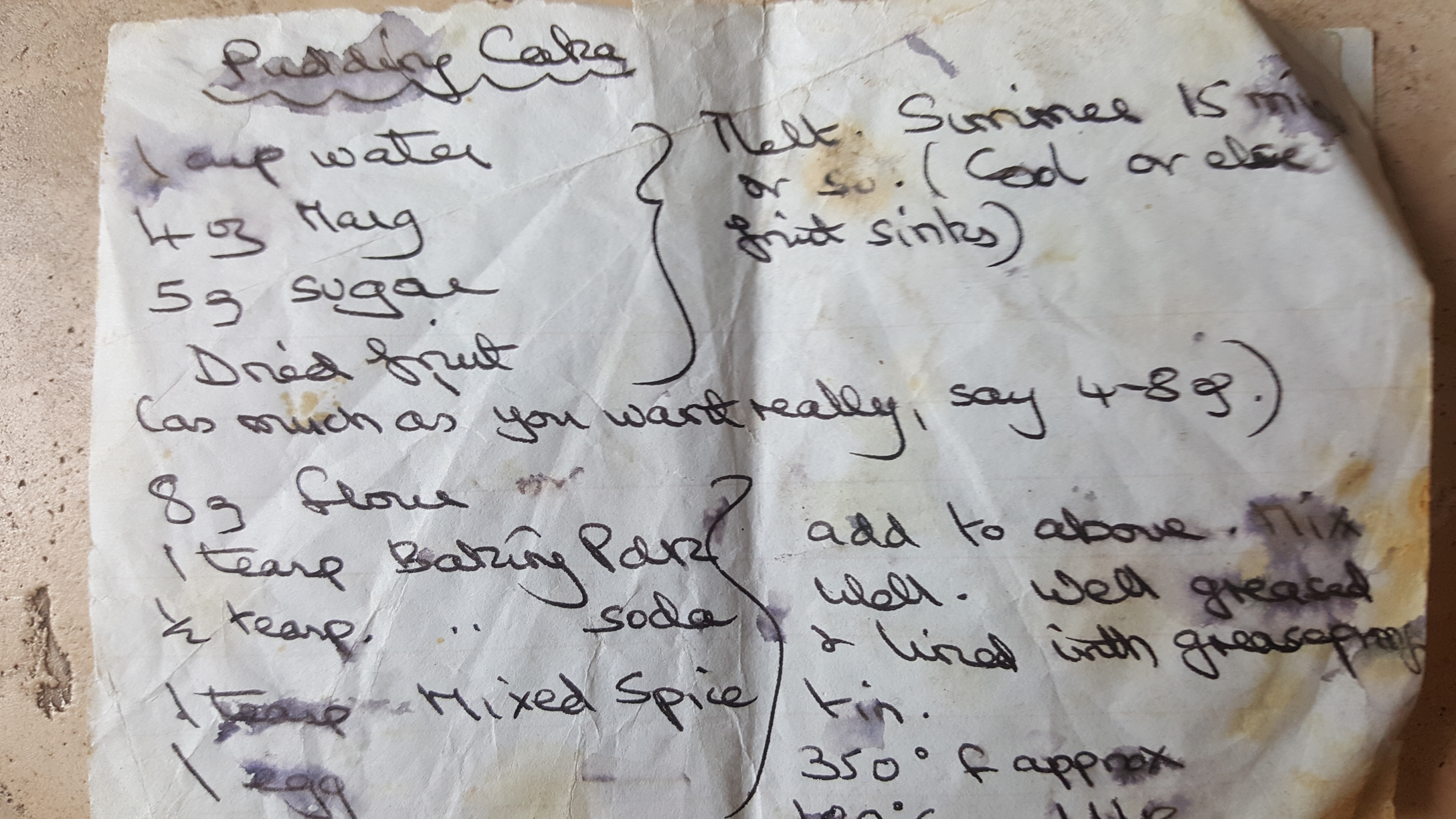

NATIONAL ARCHIVES UKI grew up some time after the war eating what we referred to in our family as “pudding cake”. My mother had got the recipe from one of our neighbours, Mrs. Moffat, who said it originated in the war, invented to cope with the shortage of eggs. I’m not sure whether that’s really true – the presence of other rationed ingredients sows some doubt – but it is true that there is only one egg, and that much of the heft is provided by water:

My parents missed the worst austerity of wartime – my mother a refugee in Australia after a slightly hairy evacuation from Singapore-Malaya on the SS Empire Star, my father occupying the critical, and hence conscription-exempt, occupation of tobacco manager in India. Still, they had grown up in the 1930s, and they instinctively taught the manners of asceticism: don’t leave the water running when you brush your teeth, switch off the lights when you leave the room, finish the food on your plate, close the living room door to keep the heat in. Although I suppose I was privileged as a child—austerity wasn’t truly over until the 1980s—my youth was, by today’s standards, a time of deprivation. I never tasted butter until my teens; eating out was a once-in-years phenomenon; I regarded grapes, orange juice and real coffee (as opposed to instant, eked out with chicory) as luxuries. Some asceticism remains, but I have not been able to resist a certain expansiveness in the matter of pudding cake, with considerable help from my sister in law, an extraordinarily good cook.

1 ¼ cup water. (In the UK, this is 1 cup, cups being larger there. I go as high a 1 ½ when I’m being lavish with the flour).

8 oz butter. (or you can use ¾ cup of oil for vegans, though it’s not as good). You can go down to 6oz fairly comfortably if you feel that two whole sticks is decadent. In Mrs Moffat’s austerity version, as in my youth, it was margarine, naturally, and precious little of it.

½ cup sugar. This amounts to 3 ½ ounces, slightly more austere than the Mrs Moffat recipe, but I do put in other sweeteners as well, like swirls of molasses, maple syrup, honey, and spoons of marmalade, strawberry or other jam..

Dried fruit. This was “a handful” in the official wartime version, but you can put as much as you want, really. Raisins, sultanas. You can also chop up dried apricot, peach, nectarine, prunes, plums, and I especially like to put in some dried pear and/or dried apple. Probably by the time I’m done it’s more like 3 or 4 cups. A little crystallized ginger is not out of the question.

Bring to a boil, cover and simmer the above for 15 – 20 minutes, then leave it to cool in a large mixing bowl for 45 more. (Best to let it cool, otherwise the fruit has a tendency to sink to the bottom – that’s how my impatient mother always did it, and that’s why we called it pudding cake.) Give it a stir from time to time, otherwise the fatty part separates and forms a skin on the surface. Once it’s cool you can add:

Grated lemon rind. Lately, I’ve started putting in actual lemon peel, mostly deprived of the pith and chopped into smallish bits, as in marmalade, adds an exhilarating sort of zing to random mouthfuls.

I sometimes put in a little almond essence, and actually a teaspoon or two of lemon juice doesn’t go amiss.

2 cups flour (can also use ¼ wholemeal as part of that). I discovered a little while ago that you can add up to a ½ cup of almond flour; if you do, then use the full 1 ½ cups of water.

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon nutmeg

1 teaspoon allspice

2 teaspoons mace

1 teaspoon ground cloves

½ teaspoon or so of salt

You can also put in a bit of ground ginger.

Best to grind the spices fresh if possible. Especially the mace, which is heavenly if kept whole until grinding time. (Mace, I was surprised to learn, is actually the covering of the actual nutmeg, fruit of the tree Myristica fragrans, though only the female produces fruit). I use an electric coffee grinder, makes it all very easy. Don’t be stingy with the spices if you can help it.

Sieve and mix that lot together while the boiled fruit mix is cooling. (The ground allspice probably won’t go through the sieve, though, and will have to be mixed in afterwards).

Beat the aforementioned single egg and stir it into the cooled fruit mixture.

Chopped walnuts, almonds, apricot pits can be thrown in here. A couple of handfuls. Apricot pits, when sweetened by the cake, are deliciously redolent of marzipan (and, allegedly, cyanide).

Stir in the flour mix, 1/3rd at a time – it gets pretty stiff by the time you’ve added the last 1/3rd.

Bake in a greased 9″ cake tin for 1 hour at 350.

If you’re feeling especially naughty, you can eat it warm with brandy butter or ice cream. It’s not unlike Christmas pud, especially if you are reckless with plums and spices. Also good with Bird’s custard (an austerity version of the real thing). Otherwise, let it cool and hide it away where your brothers won’t find it.