There’s a picture of writer and performance artist Ama Diaka sitting cross-legged on John Evans Attah Mills High Street. She’s scribbling in a book, a bag in front of her legs, and children are peering over, trying to decipher what she is writing. Ama reminded me of this image, which was taken in 2014, as we walked through Jamestown together on Saturday, 25 August, 2018, the sixth day of the annual Chale Wote Street Art Festival.

Ama spoke about the picture because I asked if the festival had always been rowdy as we walked past vendors who covered both sides of the street with their goods and pushed wares into our faces. “It wasn’t always like this.” As I looked at the throng of people milling through Jamestown, it was difficult to imagine how Ama, the lone poet, found space for her performance on the same street we were threading. Jamestown looked like “everything was suddening into a hurricane” of human movement, to borrow Binyavanga Wainana’s words. There was crowd control in the form of stern-faced policemen, who intermittently rode around on trucks, blaring loud sirens, but that only gave order to the mass of people; it didn’t staunch its flow.

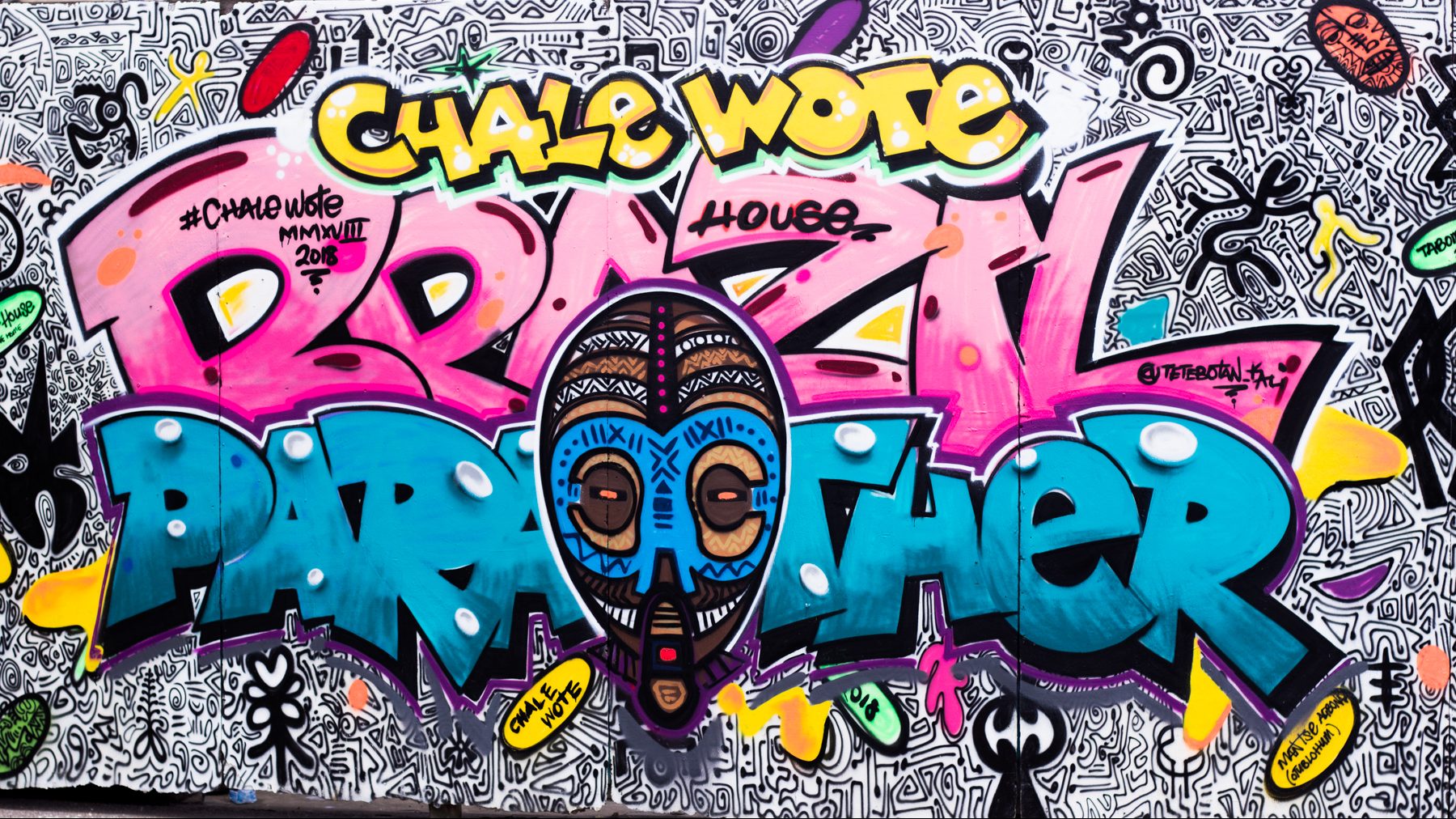

Chale Wote, now in its eighth year, had begun the previous Monday with a Ga procession, led by men in white garments who poured libations as they marched through Jamestown, part of a cleansing ritual that opens the festival. Then the procession moved to Brazil House, where Shika Shika Art Fair, an exhibition of photographs and painting opened with dance and vocal performances. The name of the festival itself is from the Ga expression for “man, let’s go”, which also doubles as an expression for flip flops. The theme of the 2018 edition is ‘Para-Other’: “a transatlantic shortwave that transcends language and geography,” as the press statement for the festival explained. “Para-Other requires new knowledge fractals, codes, symbols, and sounds that transmit our core creative intent where imperial languages fail us.”

Perhaps in pursuance of transmission that avoids imperial languages, the statement is also published in Ghanaian Pidgin: “Para-Other be phenomena, e be tin we go fi use take change how yaanom do tins wey we no dey fi move. E be mind tin. E dey like shortwave radio wey we go fi take travel anywhere. Para-Other check like some state wey we no sheda be human – we turn som oda tin. We dey use am link Black pipol for every corna for dis earth. E be some code, e san be sound we no hear before but e dey here already.”

I do not pretend to grasp the proper meaning of these statements—not in English, not in Pidgin. Over the course of the festival’s first five days, however, a theme began to form that suggested the vision of the organisers. Chale Wote has always been concerned with grand themes about the the existence of black people in Africa and the diaspora. Addressing concerns of black people through ambiguous themes is a Chale Wote shtick. The last three editions of the festival were a trilogy themed African Electronics, Spirit Robot, and Wata Mata. Those three years of considering African liberation—through contemporary art that reflect the past and imagine Afro-futures exhibited in Jamestown, an historical site of bondage—could have been titled Liberation Part I, II and III, with the esoteric expressions as subtitles. For the organisers, clarity isn’t the name of game, but their obfuscation isn’t without purpose.

The labs, panel discussions, and film screenings this year all pointed towards similar ideas: collaboration, African unity, and how these notions are reflected in different forms of artistic expressions centered on the black body. The exhibiting artists were from all over the world, another sign of a connection the theme was supposed to reflect. The mix of artists on the continent and in the diaspora having conversations about their works and pingponging ideas presented a world of possibilities, which many of the attendees were eager to enter. Samia Nkrumah, daughter of Kwame Nkrumah, was present for a brief chat on the fourth day of the festival, as her voice is part of a film Awaking Sankofa by Donisha Prendergast, Ian Keteku, and Komi Olaf. In the appearance of the daughter of Ghana’s first president was a glimpse of the idealism some of the artists spoke of, a past incarnation of a future they desire.

Some of the suggestions that came out of the conversations after the Awaiting Sankofa screening were curious. After the creators had spoken, a member of the audience asked for a unifying African language, and I wondered why that was requisite to unity. Another spoke of how the ‘west’ controls the black narrative using the framing of CIA Agent Everett K. Ross (Martin Freeman) as a saviour in the movie Black Panther as proof. “It may sound like a conspiracy theory,” said the conspiracy theorist. Then a shift occurred.

“Do you know who you are?” a lady with blonde-dyed low-cut said, after the conspiracy theorist. “Find out stories of whom you are. We can’t sit down here and talk about our people who we don’t even know.” As she spoke, tension spiked the tent at Kukun in Osu where the screening had been held. She was breaking away from the idealism of the group and infusing the conversation with a dose of practicality delivered like a sermon. When she returned the microphone, there were pensive nods, and sighs, and murmurs. Comments that followed were laced with the awareness that ideas spoken in the Chale Wote conversations held at the National Theatre of Ghana and Kukun are removed from the reality experienced by people who do not have time to attend week-day symposiums about arcane theories, whose only contact with ‘Para-Other’ will be at the exhibitions in Jamestown during the weekend. For a moment it seemed everyone understood that for any practical manifestation of the Africa they wanted, the artists needed to reach a critical mass of people who can be mobilized into a movement. This, perhaps, is the argument for the greater Chale Wote festival that happened during the weekend in Jamestown: there, artists were supposed to find a large audience that would pay attention to their ideas.

“The story of Jamestown began with the erection of James fort by the British in 1673 – 74,” writes former Mayor of Accra Nat Nuno-Amarteifio in a comprehensive essay about one of the city’s oldest districts. The Portuguese arrived on the shores of Accra in the 15th century. They traded with the Ga locals, but their relationship ended when they built a lodge in 1576 that was opposed by the Ga king. After subsequent interactions with other Europeans, the Ga King Mampong Okai granted permission for the Dutch West India Company to build a fort in 1649, against the wishes of his people. The fort was named Crevecouer, and later became Ussher Fort after the Dutch sold it to the Brits in 1868, who renamed it after a British governor Herbert Taylor Ussher.

“The British fort was the last European trading post to be erected in Accra. It was the smallest of the 3 forts and was built about one and half miles from the Dutch fort. It stood in a village called Soko owned by the Ajumaku and Adanse clans. The site for the fort was leased in 1672 to the Royal African Company by the Ga Mantse Okaikoi.” Dutch, British, Ga. This is the beginning of the history of a place tied to Ghanaian history through slavery and the story of independence, via Kwame Nkrumah, who was imprisoned at the James Fort Prison.

“King James I of Great Britain granted a royal charter to the company to build the fort and gave permission to name it after himself,” continues Nuno-Amarteifio. “Jamestown’s cosmopolitan mix of peoples started literally at its birth. The British brought slaves and labourers from the Allada kingdom in Nigeria. Allada was a major regional market for slaves and the word Alata, a corruption of Allada, entered the Ga language to describe people from Allada and survived to identify Yorubas in general.”

I, a Yoruba man, finally sneak into this story.

Ama had earlier told me of the relationship between Ga and Yoruba. She did this while we were at the Goethe Institute in Accra, for an edition of Ehalakasa, a long-running spoken word poetry and music project created by the poet Nii Lantey. “This is Ife, my writer friend from Nigeria,” Ama introduced me to her friends at Ehalakasa. Then she turned to me and said, “I should stop saying this writer thing.” Ama and I met at the Farafina Trust Writing Workshop in Lagos in 2016. In Lagos, and in many parts of Accra, she is better known as the poet and singer Poetra Asantewa. And Ehalakasa is part of her growth as an artist, for it was on its stage, back in 2010, that she took her practice of poetry from writing to performance.

The edition of Ehalakasa we attended took Accra itself as its theme, part of an ongoing exhibition on African Mordernism: The Architecture of Independence. Most of the poets who mounted the Ehalakasa stage spoke of the ills of Accra—the mess of it all and the way it lures people from the hinterland with a beauty that’s nothing but a mirage. They could have been talking about Lagos too. And maybe all young poets in Accra are political, because that’s all I heard in their poems. One of the poets performed in Ga, and that was when I asked Ama what language he was speaking. I was sure even the Ga man’s poem was about politics, audience laughter notwithstanding. Another poet, a tall man in white t-shirt, muffler, and boots Ama thought ugly climbed stage, muttered a brief introduction, adjusted the microphone to match his height and grabbed it by the neck, changed his countenance in that way spoken word poets do when they transition to performance mode and said, “Colonialism.” I turned to Ama and rolled my eyes.

Everything in Jamestown reminds you of a time when the continent was occupied by white people—“Colonisers” as the movie Black Panther has now made it trendy to call them. They’re responsible for the beautiful architecture which contrasts with what you encounter once you crouch through the doors of James Fort, into dark, damp prison cells that remind you of how your ancestors were treated centuries ago, even if you’re the kind of person who rolls their eyes at a poet who begins a poem with the ‘c’ word.

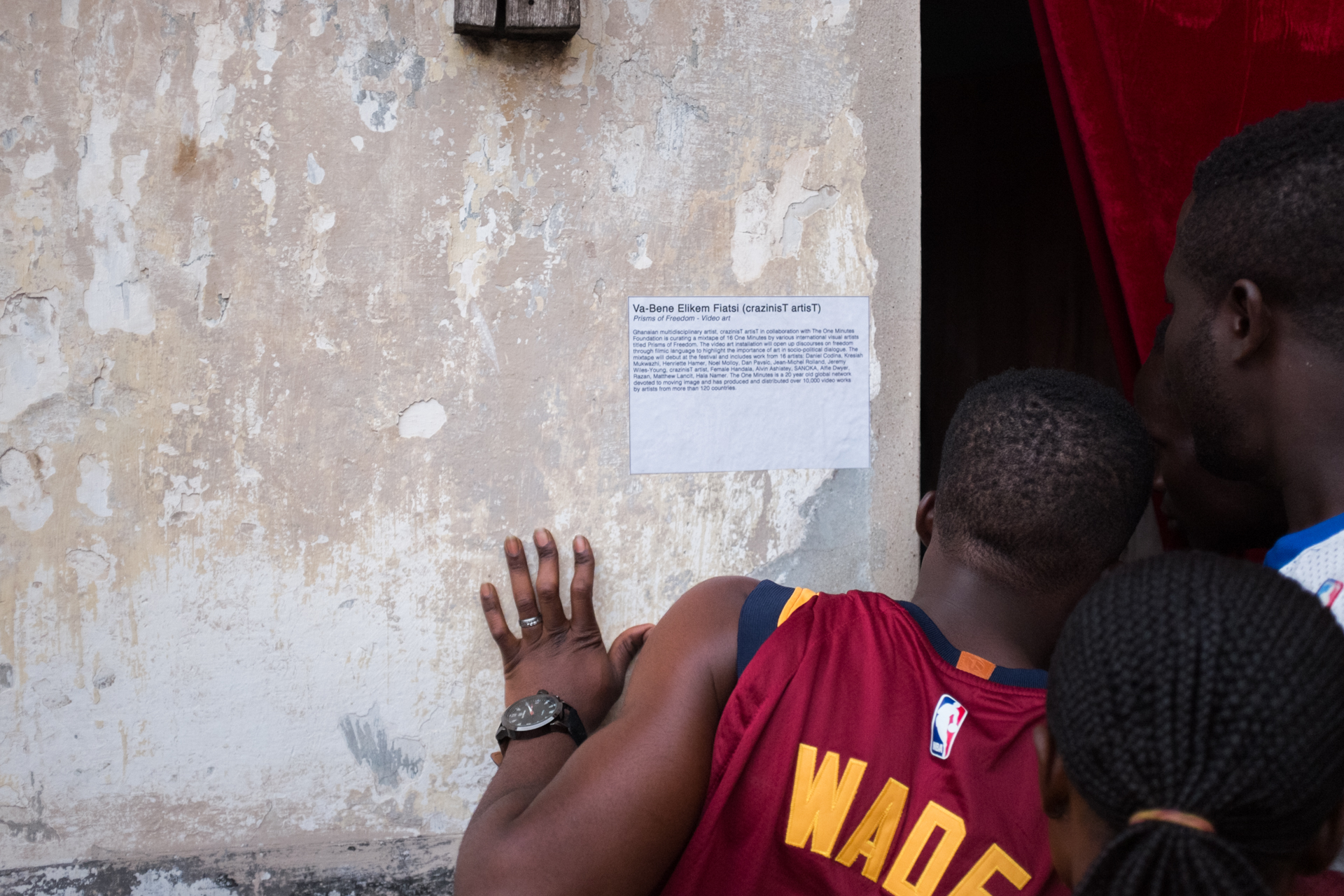

The art installations featured at Chale Wote are crafted to remind you of our colonial past and its horrors, which the walls of Jamestown render in stark detail, and the present condition of black people around the world, which still bears echoes of that past. The first performance I encountered as I dipped into James Fort was agbaWnu by Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi, an installation that features a body lying on a wooden frame that holds a metal bed of spikes suspended with chains, a piper under the body, a man performing a ritual above it, all symbolic of the violence that has been visited on the black body across time. Other exhibition spaces in Ussher Fort, Brazil House, and Old Kingsway building featured art like this, created to coax the audience into contemplation—considering both the work, and the walls against which it appears. As I watched Lesley Asare’s Body Arcana in Usshe Fort, her body writhing as she transitioned through what looked like yoga poses on a white mat that mapped her movement through black paint on her palms, I realised that here in the land that gave the world azonto was a dance performance that is unyielding to easy commercialization and cursory glances. Yet, that is what most of the audience have to give.

In Ussher Fort, the white walls were covered with pastel-colored corrugated sheets stitched together with an intricacy that was excruciating to even think about. This installation by Tei Huagie featured four long humanoid figures, which became the backdrop for selfies. Huagie’s work wasn’t alone in its existence as background for vanity. Most of the artwork in and around the forts become props for people repurposing them into photoshoots.

A large part of Chale Wote—from the screenings in the first few days of the festival to the exhibitions in the forts and building of Jamestown—may be intended as a consideration of our collective existence as black people, or whatever else Para-Other is supposed to mean. But on the street, what existed were traders in tents trying to convince passersby that a gown or jewelry or Kenkey was the best way to spend their money, boxing boys testing their powers in rings of chalk drawn on asphalt, stunting skaters putting on a show, bodybuilders flexing their pectoral muscles, face painters with palettes of watercolors looking for someone to beautify for a cedi, portrait artists working their pencil on paper with any one patient enough to volunteer as subject, and a throng of bodies moving skin to skin up and down James Evans Atta Mills High Street.

Ama used to be an active participant in Chale Wote, as evinced by that 2014 picture. In past iterations of the festival, she had performed her poetry both solo and in collaboration with other art projects. As we move through Chale Wote, she says hello to the organisers and chats with them like family. But this year, she’s not Poetra the performer sitting on asphalt. Instead, she’s Ama Diaka, the owner of Yobbings, a card company with a stand beside Bible House, where her cards, which feature jaunty descriptions like “I’m in this for your bum bum” are displayed. Commerce on the streets has sent most of the art into the forts of Jamestown, where they are ready to be co-opted by couples looking for chic selfies. Perhaps this is what it means to host a successful street art festival: people will come in large numbers, do whatever they want, and even ignore the art. Freedom.

Nkrumah, former prisoner in James Fort Prison, is said to be responsible for the final economic decline of Jamestown. In 1962, he commissioned Tema harbor, which replaced Jamestown as a center for commerce, reducing it to a fishing community. According to Ama, in the early years of Chale Wote, which debuted in 2011, the people of Jamestown weren’t fully aware of its economic potential. Seven years later, they’ve taken ownership of the festival and its appurtenances. Bars and shops sported Chale-Wote-tagged banners, and there was food at every corner. Ama and I bought kelewele just opposite Jamestown Lighthouse, and pork at the Mantse Agbonaa Park, which had been transformed into a massive cookout.

Ama took a cab out of Jamestown as the afternoon sun started its slow descent. Right after she left, President Nana Akufo-Addo made an appearance. The festival has always been supported by the Accra Metropolitan Assembly, which grants permission to block John Evans Atta Mills High Street for the duration of the festival, and offers the services of policemen to secure the events. But the same couldn’t be said for the greater Ghanaian government.

“When we started Chale Wote, every year we sent letters and proposals to the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Creative Arts and we never heard anything from them,” Mantse Aryeequaye, one of the founders of the festival, said in 2016. “If you send things to someone for four years and they ignore you it means they are not interested.” With the appearance of the President and a 300,000 cedi grant from the Ghana Tourism Authority, it seems the government has finally joined its people in paying attention to Chale Wote. But attention comes at a cost.

Movement in Chale Wote occurred in waves that flowed in and out of John Evans Atta Mills High Street. These waves weren’t dissimilar to the ones that crash against the beach of Jamestown harbour. Not dissimilar to the ones that carried black bodies across oceans towards foreign lands where their descendants, seeking freedom, would eventually sing ‘Wade in the Water’—the song that came to my mind as I followed a chain of boys that had formed in the middle of the street to ease their passage through the crowd. I laughed at the ability of my mind to wander from the bustle of the street to a place where the ‘c’ word appears in caps, my own transatlantic shortwave. Commerce might be at the soul of Chale Wote on the streets, but its higher concerns are ever present, even when the crowd seems oblivious of it.

On Sunday, I returned to Jamestown alone. I couldn’t convince Ama to accompany me to push through bodies as I took pictures. Going from one end of John Evans Atta Mills street to the other felt like a chore.. The previous day, I had seen young boys with grabby arms giggling as they touched women and ran, costumed men leading processions and firing guns indiscriminately, and motorcycle riders hoping their revving engines and blaring horns would create a path to pass through the crowd. I had a feeling that anything could go wrong, yet nothing did.

As I poised myself to join the crowd, I felt like those little kids looking into Ama’s book in the 2014 picture. I was intrigued by what existed in the crowd, yet ambivalent about what it would take to get a glimpse of it. A part of me wanted a Chale Wote that is a festival of high ideas, yet not so high that every conversation becomes a reexamination of colonization; a Chale Wote that is free to accommodate everyone, yet not crowded as to make finding its art difficult. But these are mere wants. “Man, let’s go,” the festival is called. And I plunged back into that crowd, making my way to the other side to join a final concert at Mantse Agbonaa Park.

(captions)