Jennalee is one of those white girl names that didn’t exist before like, 1945 but is the fifteenth most popular name for a baby girl in Indiana today, I bet. I knew countless Jennalee’s when I was growing up there, but only one consumed my thoughts between the ages of 12 and 14.

Looking back, I can say it was a borderline sexual obsession in the sense that I was fixated on every aspect of her being. She wasn’t almost perfect, she was in her essence perfect. She had long, blond hair, shiny and perfectly straight. She had a dimply smile, a thigh gap, and a perfectly toned belly. She had boobs but not the aggressive kind. She was rich—her MySpace had all these pictures of her and her friends playing in her huge green lawn behind her huge house. Her family was also hot. Honestly, even her dogs were hot, at least from the photos on MySpace.

But Jennalee wasn’t like the other hot girls in school. She knew she was hot but she was nice about it. Unlike the other hot girls, she would talk to me, shy and awkward with my fuzzy upper lip, and make eye contact and stuff. She didn’t look like a middle schooler like the rest of us—that’s when I was obsessed with her—she looked like a baby prostitute decked out in hundreds of dollars of Abercrombie. Like I said, she was perfect.

One night before we started the swimming portion of our sixth-grade gym class, I spent the evening doing the classic middle school body shame thing, standing in front of a mirror in my one-piece fixating on all the things wrong with me.

Chief among them were my arms. I wasn’t actually fat, I reasoned, my arms were just slightly chubbier than the rest of my body, which made me look way fatter than I was. I pinched my arm fat back, thinking of Jennalee’s perfectly toned upper body. She obviously looked great at swim class the next day. My arms remained a fixation well into adulthood, the one part of my body I didn’t show during my rebellion in high school and college, when my relatively conservative parents scolded me for wearing miniskirts and denim shorts.

As I grew older, and woke-er as it were, I learned about internalized racism. I watched Bend It Like Beckham, where a brown girl like me kisses a hot white guy. I read Joy Luck Club. I listened to M.I.A. I realized why physical aspects of my body, like my hairy face and the way my nose sloped, brought me intense shame. I did the thing where I could swap stories with other brown girls about wanting blond hair and having a doting immigrant mother. Like me, they had their own Jennalees. Everyone did. It all made sense.

Then, right as I graduated college and began writing on the Internet for money, I learned to package my Jennalee stories, sometimes wrapping them in deep irony, but usually in that half comedic half educational tone that makes white readers be like, “Wow that’s crazy, what a fun way to learn about your culture!” and brown readers be like, “lol I know EXACTLY what you mean.”

Post-9/11 neoliberals love a passing Muslim woman who can crack burqa jokes without missing a beat. That was me. When I nailed telling a funny story, usually one that had caused a decent amount of childhood trauma, I watched the faces of my rapt audience erupt with laughter and relief that they could, as white people, understand “the brown experience” and still laugh with me. I felt liked by my peers in New York media, and pride—not only had I overcome the deep shame I felt being brown in a white Indiana suburb, I was building my reputation on it. I enjoyed overhearing people describe me as “that brown girl.” In my head it was like, “that brown girl.”

It didn’t just happen overnight, the neat, sarcastic packaging of my childhood misfortunes. I learned quickly there were two ways to answer to racism: borderline bullying to keep from being bullied myself, and a self-deprecating humor that brought me in on the joke instead of the other end of it.

My middle-school crush (this is during the Jennalee years) was a jock with flowy front bangs like the lead singer of Rooney. His nickname for me was “terrorizer,” as in, a cute way of calling me a straight up terrorist. I hated it but took it, countering with my own problematic pet name for him: “Jew.” His Zionist family no doubt raised him to bristle at the tone with which I delivered it, too. Our racist teasing took the power out of a label that would otherwise push me into a rage I was barely capable of handling as a tween. It was a lesson I carried with me into young adulthood. Why not make myself the punchline before anyone else had the chance to?

I rarely went back to Pakistan, where I was born, and when I did it was usually for a work trip, no longer than two weeks at a time. I would film short documentaries, mostly about depressing stuff happening in Pakistan. But each trip was like a visit to Epcot—I interacted with Pakistani culture like a white person would. I’d go shopping and to the restaurants after work, buying traditional clothes and eating masala lamb chops, exclaiming things like, “Now that’s the stuff.” My driver would tell me funny personal stories, and I’d react like my own white dinner audiences: with laughter and relief that I could understand a real Pakistani’s “experience.” I enjoyed being among my people. I would literally think that as I gulped down samosas, sweating shoulder-to-shoulder with my fellow samosa-eaters at a street stall. “God, I love my people.”

I quit my job in New York and moved to Pakistan a year ago, for reasons I still can’t quite put into words. I told myself it was for work, which made sense. I’m a journalist and my passing cuts both ways—I have brown skin, and my relative fluency in Urdu makes it easy for me to pass as a real Pakistani, thus more able work in places where white foreign correspondents can’t. My editor told me I was the best of both worlds. What he really was saying was I was a coconut: white on the inside, brown on the outside. I took it as a compliment.

I moved to get away, from a lot of things, but especially from white people. Not the people themselves, but what living among them was doing to me. Even as I overcame the obstacles of being a woman of color and an immigrant, my whole thing was still in reference to them. What happens when I remove them from the equation entirely?

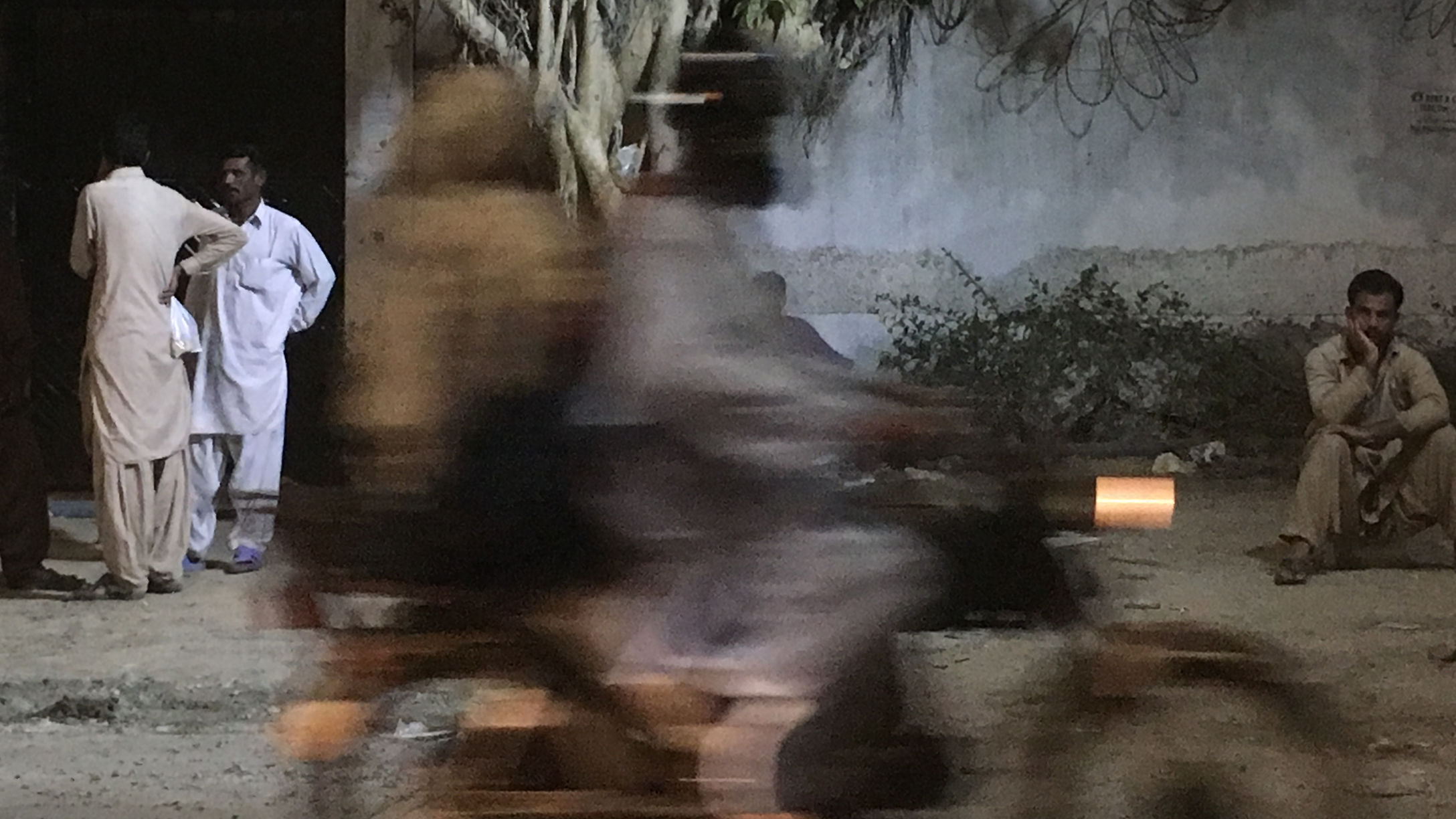

Photo: Meher Ahmad

Photo: Meher AhmadNow I’m here, and months go by without my seeing white Americans except for on the news. I’m surrounded by Pakistanis. I chose, of all places in Pakistan, to move to a city of 20 million people. They’re all brown people and they’re everywhere. There’s no escaping them, like there’s no escaping white culture in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

My shtick doesn’t work here. It works in New York City, it works with Pakistani-Americans, but it doesn’t work in Pakistan proper. It makes me miss being surrounded by the white people I ran from, like no one here even gets that I was good at explaining being brown! But Pakistanis don’t really know what it feels like to have a Jennalee, nor do they give a shit. Maybe I shouldn’t give a shit. It’s the kind of wishy-washy American emotionalism people who grew up in Pakistan look down upon.

But as much as I try, I can’t shake the inherent corniness of being an American that I was raised with. The things I miss from the cushy American life I left behind were at first material (embarrassingly, kale, kombucha, and a Chipotle burrito bowl are high on that list, a good indicator of how white I really am), then more abstract. I took for granted how living in a new-money suburb left me largely unaware of how societies older than 200-some years work. Here, people don’t judge me because of my brownness. They judge me because I come from a family of civil servants instead of land-owners with generational fiefdoms. No amount of wealth or foreign education will correct that defect.

Photo: Meher Ahmad

Photo: Meher AhmadI’ve caught myself strangely nostalgic for a childhood I resented, where buying a Dooney and Bourke purse was all you needed to be accepted by the rich kids. There’s something perversely egalitarian about that, and uniquely American, too. Me even thinking that is so American. You can compensate for your middle-class parents and brownness with cash. Pakistanis, especially the elite ones, can sniff out my middle-class stink through my educated, American accent like a bloodhound.

I’m still here, though, and I probably will be for a while. Despite my irreparably middle-class background, I’ve been wooed by the Pakistan I thought I was gobbling up at the samosa stand back when I came for work trips. When I moved here, I told myself I’d stay as long as the third world charm doesn’t wear off. The carriage hasn’t turned into a pumpkin yet.

I love when the power goes out in the night, as it frequently does, that the family I live with sometimes sits in their car, blasting their AC and listening to music until the load-shedding passes. I enjoy the eerie calm that settles over the city on days the government decides to shut off all the cell towers due to “security threats,” forcing us to rely on old-fashioned forms of communication like, I know, land lines. I love that the security guards at the building where I work know to refer to me with a nickname only my family calls me by, Mehru, without me ever having to explain that to them. Though my passport says otherwise, I know I’m Pakistani, and that this dusty corner of the world will always be a place that will take me in no matter what happens to the place where I grew up.

There are virtually no bars in Pakistan—alcohol is banned, in keeping with the Islamic law of the land—so I can’t drink when I’m bored. I go to salons and get elaborate treatments to pass the time. Multi-step facials, massages with bespoke oils and the like. With local rates, it’s a far cheaper and healthier way than drinking to think about nothing. The salons are women-only (one of the few perks to living in an Islamic society) so customers walk around near-naked, in sleeveless cotton mumuus issued by the salon.

I’ll be sitting in a brown pleather salon chair, pushed up next to a half-dozen women sitting in theirs, a few older but most around my age, in our late 20s, all of us zoning out as salon workers massage our faces with some useless tonic. They sit, like me, aimlessly looking at the wall as someone paints their nails or threads their eyebrows. Their arms, like mine, are slightly chubbier than the rest of their body.

Meher Ahmad