La Comédie humaine is the diary of American expatriate Claire Berlinski’s amazing journey onto the Parisian stage. (Names have been changed to protect privacy.) If you missed the Introduction, we urge you to begin there.

I took a seat in the front row. So did Fabien. He opened his laptop, and began tapping away like a man on a commuter train writing a memo about a filing deadline. Our DPO is tasked with monitoring compliance with data protection laws … Tap-tap-tap …. awareness-raising, training, and audits … Tap-tap-tap.

I was fascinated by his lack of presence. I’d never have guessed he was an actor. Even if he’d mugged me, I doubted I could have picked his face out of a police lineup the next day. I wondered if this made him a versatile actor who could play any character he was assigned, or if his career had been a vale of tears…

One by one, others began straggling in. I didn’t know whether they were professional actors, or my competitors, or other students who’d already passed their auditions. For a moment I allowed myself to imagine they’d all be eliminated automatically for being late, leaving me the victor by default. But it was clear within minutes that none of them had studied with Wendy Alane.

All of them milled around, tutoied and began an enthusiastic round of cheek-kissing—the standard Paris two-cheek. Everyone kissed Fabien, too. The French often do this to introduce themselves—and it’s not, actually, a longstanding French tradition. The kissing-everyone thing began during the ‘68 student uprisings as an effort to promote familiarity over hierarchy. (Most don’t know this. A French mayor caused a scandal a while ago when she announced that she’d just had it with kissing all 73 of her colleagues every single morning. It was a complete waste of time, she said, and she simply wasn’t going to do it anymore. Hell broke loose.)

Fifteen-odd aspiring actors were now assembled, all of them doing exactly what Wendy Alane said never to do—whingeing about their day and the horreur of some problem at the office. They seemed so familiar with each other that I began to suspect they’d already been chosen. Had I just been thrown in the middle of an established class to see if I swam or sank?

So I ditched Wendy Alane, and starting kissing my rivals and complaining about my day. I kissed Dominique and Anne, the two older women—maybe in their mid-sixties, but it’s hard to tell in Paris, and Marc and then Alain, who both looked to me like high school students. Marc wore a cravat, but it only served to make him look younger, as if he’d borrowed it from his father. I kissed Solange, who was plump and gregarious—I liked her despite myself—and Louise, whom I instantly pegged as a stuck-up bitch.

Balthazar, a gawky guy with a bouffant blow-dry, came over to kiss me. I asked him what drew him to the class, trying to figure out just what was going on here. He told me that he delivered sushi by day, but his dream was to go to America and make it big in Hollywood. He pulled out his phone and showed me a selfie, taken with Scarlett Johansson. He stared at her moistly, then offered to help me with my lines.

Céleste didn’t really give me any clues about how this worked, either. She wanted to try acting classes because “It is all so stressful and narrow at work, I am like a machine! I must do something créatif, pour changer mes idées.”

Everyone in Paris complains of stress and an entire economy is organized around alleviating it. Within walking distance from my apartment may be homeopaths, osteopaths, sophrologues, hypnotherapists, aromatherapists, psychotherapists, and massage therapists, yoga studios to suit every level of anxiety (hot, Ashtanga, gay, circus), and oxygen bars. (Of course, the source of everyone’s stress is that no one earns enough money to use these facilities.)

Martin was a tall man his early forties who wore a leather jacket and spoke very quickly, even for a Parisian, using a lot of slang. He was holding forth before a batting-eyelashed group of ladies, telling an amusing story involving a motor-scooter and a police officer. He used a word I didn’t know: relou. “What does relou mean?” I said.

The batting-eyelashed ladies tittered. I realized the word must be vulgar, but Martin took it in stride. He explained that relou is verlan. I got it. Verlan is something like Cockney rhyming slang. In other words, it’s lourd, backward. Fat. A fat dork of a policeman. I repeated “un policier relou” to make sure I remembered the word. His face grew concerned. “Don’t say that, though,” he said.

Liane, a gamine little creature, asked me where I was from. When I told her I was American, she sucked in her breath and praised my French lavishly. “Oh là là, c’est extraordinaire. Tu parles si bien français.” Americans who speak French are objects of wonder, like Dr. Johnson’s dog walking on its hind legs.

Fabien’s voice boomed through the room, cutting through the chatter. “Okay!” he said energetically. He’d magically transformed his voice: the Senior Data Analyst had become a carnival barker. He pronounced it WHRROA-kay! “Let’s begin!”

He told us all to get on the stage. We all shut up and did what he said.

My first reaction was surprise. The stage lights were so bright that they were blinding, literally. I couldn’t have seen the audience, had there been one. In all my years of watching concerts and plays it had never once occurred to me that I could see the performers, but they couldn’t see me. I blinked as the implications of this dawned on me and I reinterpreted my entire childhood and my relationship with my mother.

“WHRROA-kay, everyone!” Fabien interjected. “Let’s warm up. I want everyone to begin walking around the stage. Naturally. Just walk.”

“All the stage,” he boomed. “Walk everywhere, go everywhere, get un feeling for the stage. You must fill the whole stage.” I tried to figure out what that meant. I made sure I went to every corner of the stage. We all did this for a few minutes, silently. I tried to show Fabien how naturally and realistically I could walk in a circle.

“WHRROA-kay! Très bien! Now l’échauffement.” The warm-up. “Begin with your neck. Roll it clockwise, like you’re trying to stretch out the tension.” Anne stopped in her tracks to roll, but he admonished her. “Keep walking.” So this was a test to see if we could walk and chew gum, I thought, which reminded me that I still had a wad of Nicorette in my mouth. Did that look bad?

“WHRROA-kay,” Fabien interrupted. “Now let’s warm up our voices. Everyone in a circle.”

I got a little nervous.

“First, the vowels. A! E! I! O! U! Now, you’re not singing. Breathe into your belly. This comes from your belly…. “En haut voix—at the top of your voice—for as loud and long as you can.”

Everyone inhaled simultaneously. Fabien started bellowing—AHHHHHHHH!—and we all followed suit.

“AHHHHHHH!,” we screamed in unison. As a rule, the French are quiet and speak in low voices, so I was surprised to learn they were able to shout as loudly as I could. But for some reason, I outlasted the rest of the class. Fabien looked directly at me, approvingly, and said, “très bien.”

I was thrilled. The others looked at me strangely. I was tempted to try it again, but I feared that would be obnoxiously competitive, so on the next vowel, I stopped when everyone else did. “WHRROA-kay, très bien,” he said after a few more vowel exercises. “Now we begin forming our emotions and our reflexes. Keep walking. You are late. You are late to an important meeting, and you are impatient with everyone else who is in your way. Feel the impatience. Show us your impatience.”

Oh, wow, I thought. I got lucky. That’s my natural state.

We all picked up our pace, going faster and faster. Out of the corner of my eye I checked to see what the other students were doing. Some were pretending to check their watches. I thought that was over-acting. I managed quickly to infuriate myself with everyone else on the stage. They were all walking too slowly and getting in my way. I checked out Louise: She looked the same. Did she have any emotion, I wondered, but “bitch?” Did I have license to shove her out of my way, I wondered? Would that be good acting, or going way too far?

Fabien clapped, before I got the nerve to shove her. Très, très bien. Now, we change the mood. Now, take a few steps to clear yourself of the impatience, and then walk as if you’re completely zen.”

Completely zen? What the hell did that mean? Relaxed? Enlightened? I was surprised how stressed out I’d made myself, and I couldn’t quite un-stress. Envision your character. Who did I know who was completely zen? Absolutely fucking no one. I peeked to see what the other students were doing. One of them looked a little stoned so I figured I’d take the hint, and started walking like I’d just finished the whole bong on a dare. I put the soundtrack on in my head, and began strolling—Pick it, pack it, fire it up, come along…

I stopped thinking about the other students as I remembered good times.

“Bien,” said Fabien as I nodded by in my zen-ness.

I was beginning to think this one might go okay, too.

“WHRROA-kay,” he said. “Now, walk in a paranoid spirit.”

Whroa-kay.

Paranoid spirit. I slipped right into it. Dude, I think I had too much. Did we flush the rest down the toilet? But if I was actually in a paranoid spirit, I’d be trying to hide it, wouldn’t I? Should I try to look furtive and shifty-eyed, or should I try to conceal my paranoia, the way you do if you’re actually feeling paranoid? I didn’t like this one: It was making me paranoid.

We kept walking. We did “bad surprise,” and “good surprise.” We did joy. We did “dominant” and “dominated.” We did “suspicious.” And then a game where you were given two options, like rage or panic, and then find the other ones who were doing the same emotion as you and without speaking go to the same side of the stage as them.

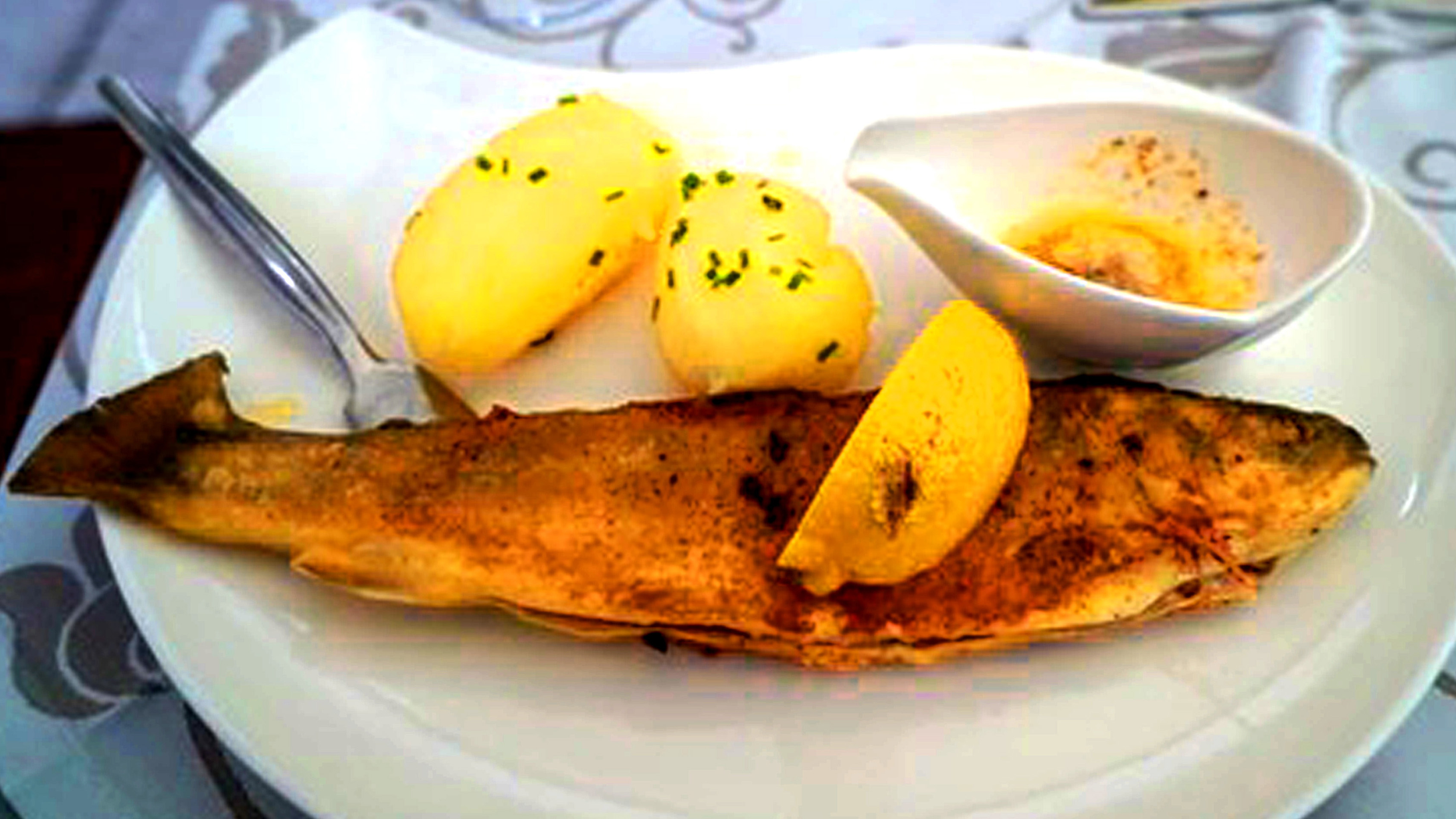

Then he put a chair in the center of the stage, and told us to start walking again. When he called our name, he said, we should sit on the chair while everyone kept else kept walking, and we should enact “anger” while saying, “La truite cuite est meilleure que la truite crue.” (“The cooked trout is better than the raw trout.”)

Balthazar sat in the chair and screwed it up: He managed to choke out the line, but instead of conveying anger, he conveyed horniness. Alain, though, was really good: He managed truly to convey the outrage of a three-star Parisian chef in high dudgeon because a diner had sent back the cooked trout.

Then I heard my name. So soon?

So I sat in the chair and just did rage. Pure rage, never mind the fucking trout. FUCK THE TROUT. I let out a howl of anguish at God, the world, everyone, man’s inhumanity to man, old kvetches who monopolize the pharmacist, Louise—the flounder, salmon, trout, everything, JUST FUCK YOUR FUCKING RAW TROUT!!!!

Whoa, I thought when I finished. The other students looked thoroughly weirded out. But Fabien was looking at me with new interest. He scribbled something in his checklist, and said something about the realism of my my gestes, “Très bien,” he said. “Bravo.” I got up again and recommenced my strolling. I was astonished that I’d just done that without being arrested, fired, or divorced. I could see how this could be fun. And why actresses are always batshit crazy.

For the next chapter, click here.

Claire Berlinski