On the highway between Belgrade, Serbia, and Skopje, the capital of the contentiously named Republic of Macedonia, the impression you get is that these countries have been abandoned. The countryside is empty. Sprawling roadside restaurants and rest stops have been boarded up; shuttered petrol stations are populated by packs of stray dogs with yellow plastic tags stapled into their ears. There is an absence of people, of community, of life. No one knows for sure how many people actually live in Macedonia today, as no census has been conducted since 2002, when the size of the population was estimated to be about 2.1 million. Most people believe that a great many people have left in recent years, fleeing poor prospects for a good life: World Bank projections on economic growth have been cut in half in the last year, and are now the lowest of anywhere in the former Yugoslavia.

But the European Union and the United States want the people of Macedonia to believe that the country has not been abandoned, that a bright Euro-Atlantic future lies just around the corner, if only some sacrifices can be made. I took the bus to Skopje to witness a vote on whether to change the 9,781-square-mile country’s name from Macedonia to North Macedonia: to outsiders perhaps a simple change, but something more serious to Macedonians, who, like people from most countries, see the name of their place of origin as an integral part of their identity. Most foreign observers, as well as the current government, described the referendum as “historic,” downplaying the unpopular name-change part and emphasizing that the choice was about whether or not the country would someday join the EU and NATO.

For 27 years, Greece has blocked Macedonia’s entrance to the EU and NATO, insisting that the name Macedonia and much of its culture and history are in fact Greek. Greece has its own northern province named Macedonia, and Athens has expressed worry that nationalist politicians in Skopje harbor irredentist claims to that part of its territory.

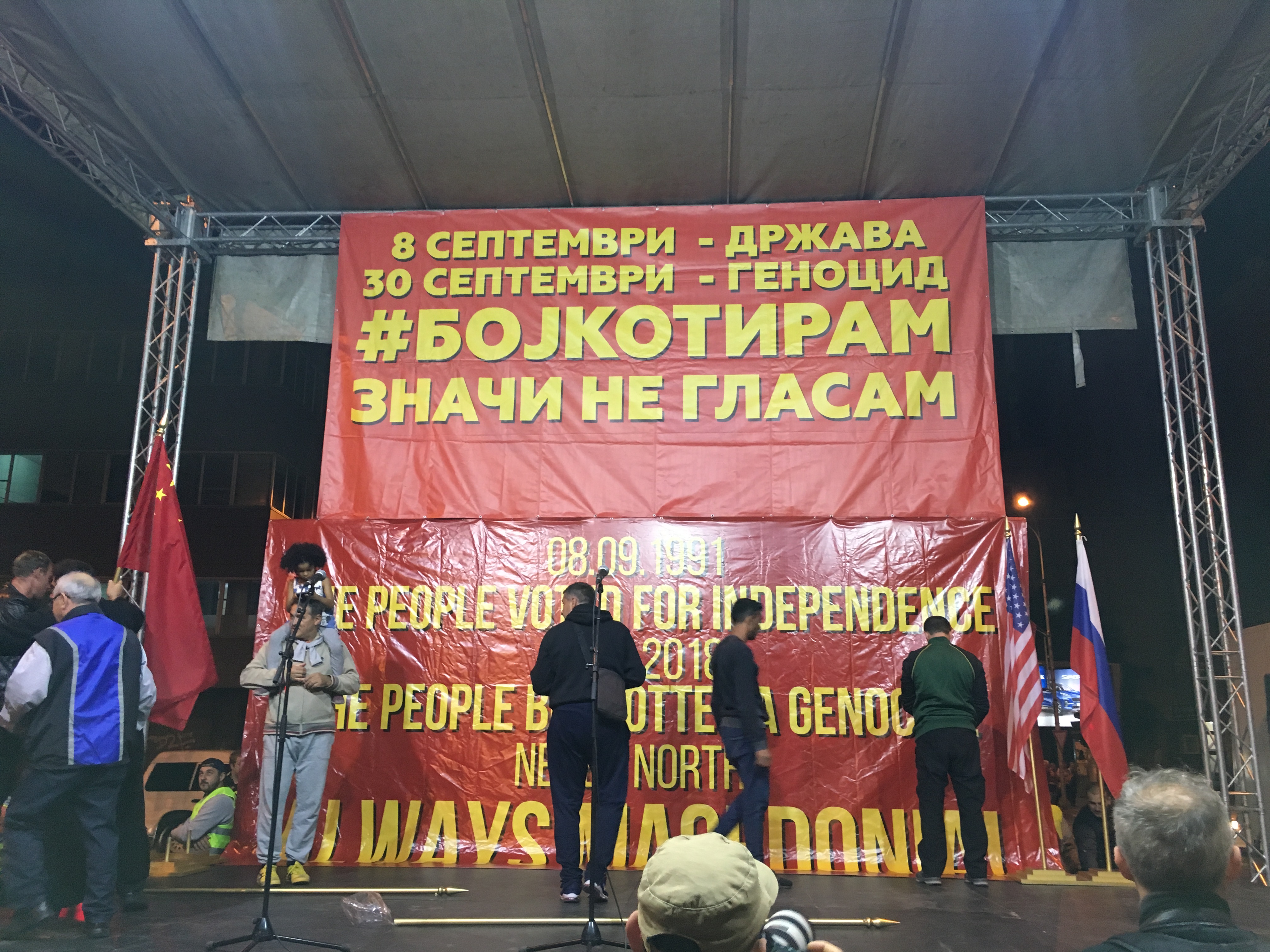

In July, Prime Ministers Zoran Zaev of Macedonia and Alexis Tsipras of Greece signed the tentative Prespa agreement that would, once ratified, give Macedonia the new name North Macedonia. Greece would in turn agree to stop blocking the country from joining the EU and NATO. The name change has wide support from Zaev’s nominally center-left party, SDSM, which came to power with strong backing from the United States in 2016. Many vocal objectors to the agreement in Macedonia support the nationalist opposition party, VMRO-DPMNE, whose members opted to boycott the referendum. The boycott campaign was organized on social media using the hashtag #Бојкотирам (“I’m boycotting”).

Macedonia also has a large Albanian minority; according to the outdated census Albanians account for at least 25 percent of the population. The Albanian population was expected to support the name change going into the vote.

On the day of the referendum, Western diplomats and NGO types wandered around the center of Skopje, drinking beer or coffee and looking hopeful. I walked around the city with two friends, making comments on the unavoidable: the architecture and the statues. The last VMRO-led government exacted an architectural and nation-building project on the capital called Skopje 2014. Around the shores of the Vardar, there are jumbo Las Vegas–style bronze statues that lay claim to the existence of a Macedonian nation. One friend joked, not entirely unproblematically, that it looked like “Jersey Shore was put in charge of a nation-building project.”

Results of the referendum started coming in during the early afternoon. We were sitting at a small restaurant in the Old Town, where much of Skopje’s Albanian population lives. The Old Town is also where much of the city’s Ottoman heritage has been preserved with funding from Turkey’s development aid agency, of which Macedonia is the fourth-biggest recipient of funds in the world.

The news was bad for supporters of the referendum, and good for supporters of the boycott. Less than 37 percent of eligible voters turned out—an even poorer result if you take into account the parade of foreign luminaries that visited Skopje urging the population to come out and vote “FOR” the referendum: European Commissioner for Enlargement Johannes Hahn, ministers from multiple European countries, the chancellor of Austria, US Secretary of Defense James Mattis. Even a recently rehabilitated George W. Bush wrote an impassioned letter imploring citizens to vote yes. The French ambassador, along with the mayor of Skopje, described the choice in stark, overwrought terms: “North Macedonia or North Korea”—name change or no NATO membership. We all thought the referendum would pass the 50 percent threshold easily. It didn’t.

The referendum was not binding but consultative, meaning that it was held in an effort to prove that there was popular legitimacy for the name change, which might have assuaged the consciences of some hesitant members of parliament who will ultimately have to vote on whether or not to adopt the Prespa agreement. And right now, that is what is being discussed, regardless of the low turnout. Zaev’s SDSM party will need to persuade members of VMRO to support the name change. Albanian parties, largely taken for granted and ignored by foreign visitors and by Zaev in the lead-up to the referendum, will likely have to be persuaded as well. This will be done the way it always is in the Balkans: by buying support with promises of administrative positions to party loyalists, by doling out small slivers of power.

The public knows this now, or so it seemed to me in Skopje. Democracy has become a dirty word across much of the Balkans, something to be sneered at, a joke. “All of this is being done in the name of democracy,” the elderly owner of my pension told me on the eve of the referendum. “In 1991, when we got our independence [from Yugoslavia], we all believed in democracy. Now we do not.”

A Pew Research survey published last year revealed some startling statistics about attitudes toward democracy among the peoples of the former Yugoslavia. Though Macedonia was not included in the poll, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia were. In Bosnia, 46 percent of respondents said that democracy was preferable to any other form of government; in Croatia, which joined the EU in 2013, 54 percent said that democracy was most preferable. In neighboring Serbia, only 25 percent of respondents said they believed democracy was the best form of government.

It’s not difficult to understand why. Prior to the referendum, its proponents said the most important indicator to watch for was turnout. When it became clear that turnout would fall far below the 50 percent threshold, the spin began. “In a parliamentary democracy, a boycott of the referendum just means people want the parliament to decide for them,” one wide-eyed believer told me. Then there was the post-referendum massaging of numbers: had the voter registration lists been updated, the referendum would have been a resounding success, many maintained, so we should ignore the turnout and interpret the referendum as a victory. One man I met on the bus was, to his credit, honest about his attitude toward the process: “I want [the referendum] to pass, and I don’t care if there has to be mass ballot stuffing and fraud for it to happen.”

The end result of all this spinning is that people know the results of democratic processes such as referenda are not taken seriously by the US-supported government and institutions such as the European Union, who’ve defined themselves as upholders of democratic values against authoritarian alternatives like Russia and China. But if the outcomes of democratic processes are malleable, and can be made to conform to the wants of those who stand to profit most financially and politically from victory, then it’s little wonder that the word democracy is becoming meaningless.

If Zaev does not manage to get the two-thirds parliamentary majority necessary for the ratification of the Prespa agreement in the coming weeks, he will likely call early elections, hoping for a stronger mandate that would enable him to pass the deal. If it works, it will end a decades-long dispute with neighboring Greece. It will mean the promise of Euro-Atlantic integration instead of limbo. But it will have been done without the consent of much of the politically divided population, who feel increasingly disenfranchised from Balkan politicians, their backers in Brussels and Washington, and from democracy itself. After Macedonia is rechristened North Macedonia, and the foreign luminaries have finished praising the country’s brave Euro-Atlantic choice, most won’t be coming back, as attention will shift elsewhere. And much of the population of the country then known as North Macedonia will continue to leave too, in numbers we do not yet know.

Lily Lynch, Essay