I don’t like making plans but some days I wake up and wish I had them. Saturday was one of these days. Almost everyone I knew including Tor was out of town. I put Merle’s leash on her and walked to the grocery store to buy some Truckee Sourdough bread. I thought I would eat toast and listen to old British dudes read Capital on LibriVox.

But on the way there my friend Erika texted me. Did I want to meet K. and L., the couple she’s friends with, and their kid. “They’re the lefty people,” she reminded me. My friend Erika is from Nebraska and she is so innocent. She would have a giant mural of Diane Feinstein and Barbara Boxer in pink pussy hats on her garage door if she had her druthers, but she is still my friend, because, you know, what are you going to do?

“You can talk to them about—stuff. Then we’re going on a train ride with their kid, and Nelson,” she said. Nelson is her kid. She had him on her own a few years ago, and a lot of people around these parts are still trying to figure that out. “Who is Nelson’s dad?” they ask, and when I say, “No one!” they say, “Come on,” and I say, “No, really.”

“I’ll come meet them,” I said. “But I’m gonna pass on the train.”

K. was American, pretty, with the sort of very boyish hair only the pretty dare have. I sat near her and with breathless rapidity she told me about her ongoing battle with the most sought-after elementary school teacher at one of the most sought-after elementary schools in Nevada County. “I’m sorry, I’m talking your ear off,” she said. But she wasn’t, and I got it. Whenever you meet someone in a small town you like who might like you, it’s possible to go kind of temporarily bonkers.

Her husband, L., was wiry, bearded, handsome, and from another country. “My country might be worse than the US, it might be the same,” he said. “I go back and forth.” They had a five-year-old with fluffy brown hair and serious eyes. (I don’t remember his name, but he really liked French fries.) Erika’s son, Nelson, who is also five, dutifully ate a small hamburger. “Where is Merle?” he asked sternly.

“She’s outside,” I said. “Tied up.”

“Is she OK?” he said.

“She’s fine,” I said. He went out and looked at her to make sure I wasn’t lying then went back to eating.

I ended up having a small beer and garlic fries for breakfast. L. and I talked about The World.

“People do not know,” L. said, his accent making his pronouncement dramatic, cinematic. “They do not know unless they suffer.”

Erika gave me a look, like, “Hey, did I hook you up or what?? Then she clapped her hands. “We’re going on a train ride! Who is excited?”

“Maybe Merle can come,” Nelson said from the back seat of Erika’s car. I had decided to go. Why not? Nelson had his arm around Merle, whose expression did not indicate consent. “I love Merle,” Nelson continued. “She is in my family.”

“She probably can’t go,” I said. “But it’s nice you want her to.”

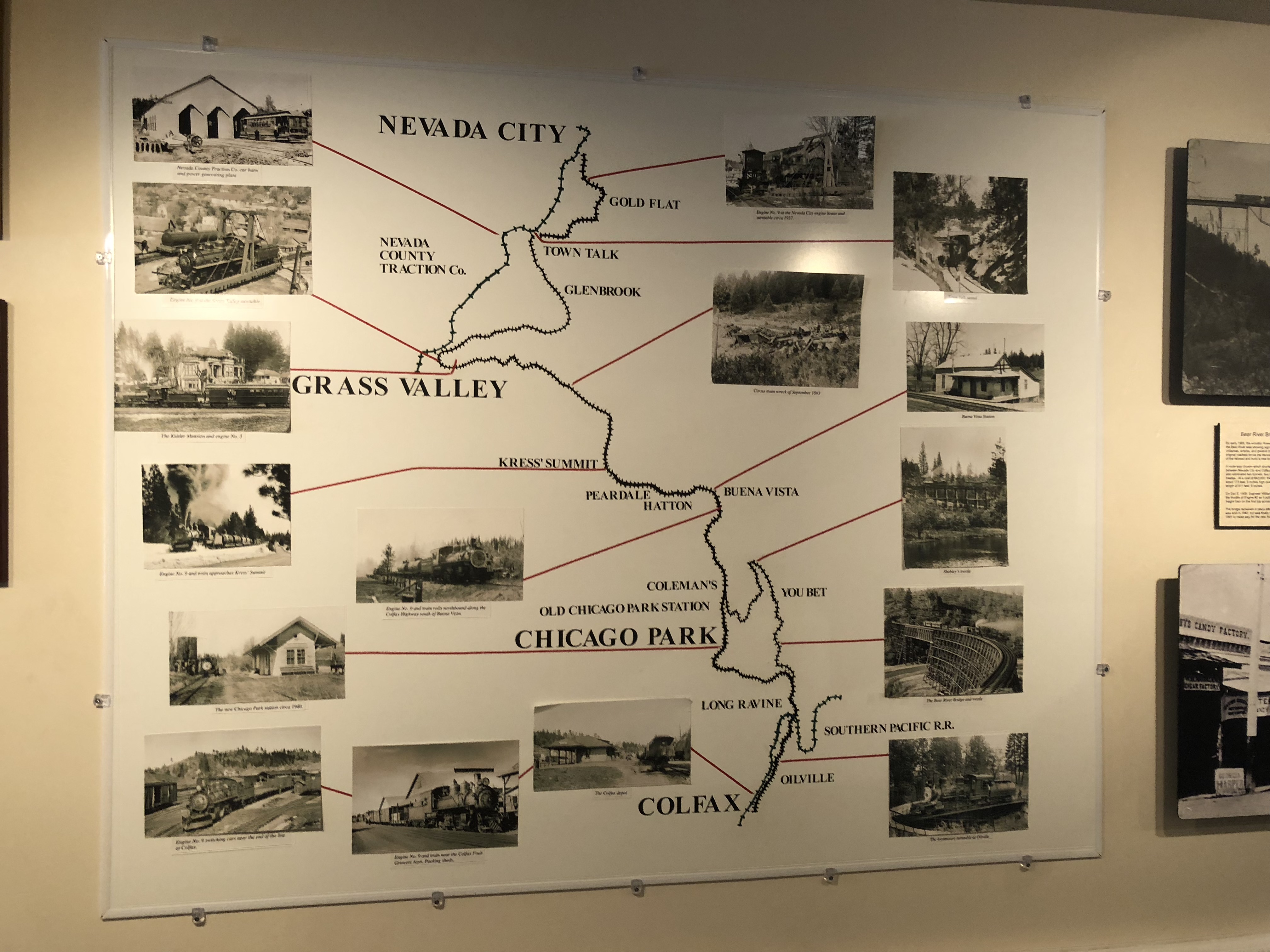

I sort of knew there was a train in Nevada City, but I also sort of forgot. It’s a little train that’s part of the railroad museum, and you can ride a short stretch of it, for a small fee. The train is sort of a tourist thing. The only locals who ride it are people with kids, because people with kids will do literally anything, even ride a train that takes you back to the same place you got on it.

Erika went off to get tickets while the rest of us loitered in the parking lot. K. helped the kids into thematically appropriate blue-and-white-striped train-engineer gear while L. and I talked about Henry Kissinger and the violent wars people will be having over water when his children are our age, or younger.

Then something truly amazing happened, maybe one of the most amazing things that’s ever happened. Erika came back with tickets and told us that Merle could come on the train. How happy Merle looked as she trotted across the parking lot toward the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Train Museum, where one waits for one’s Nevada County Narrow Gauge Train. How obediently she sat by my side on the museum’s highly varnished wooden floors, as her eager, wonder-filled gaze took in the displays of old carriages and cars. There were also beautiful old maps, and photos of gracious Victorian homes where Gold Rush and railroad magnates hung their hats. Merle turned her attention to a gleaming antique chandelier.

“That chandelier once hung in a grand home in Grass Valley,” I said to Merle. “Long before you were born.” Merle looked at me imploringly, because that is her default expression. “Of course I will buy you an antique chandelier, Merle!” I said. “You can have anything you want.”

The passengers lining up for the rides were mostly people like us, in our 30s and 40s with children and dogs in tow. But also present were men in their 70s wearing Hawaiian shirts and expressions of deep ecstasy. At first I thought there were two or three such men. Then I realized there were way more, as in, everywhere you looked was a boomer dude in a Hawaiian shirt who looked like he was tripping balls but also looked way too square for that to be true. Then I realized they were volunteers, that they were all wearing the same type of shirt because it was their sort of uniform, and they all looked super stoked not because they were cross-faded or whatever but because they just loved the shit out of old trains and now they just got to be around them all the fucking time.

One such man, taking tickets, shouted, “Blue heelers ride for free!” He touched Merle’s flank and told me he’d had four heelers during his lifetime. “Best dogs,” he said. “Best dogs ever.” I gave him my ticket, agreed with him, and we made our way toward the train.

I am a huge lightweight, and the small beer I’d drunk a half hour ago had made the sky bluer, the trees greener, the bared teeth and tongue in Merle’s panting mouth whiter and redder, respectively. Just when I thought things could not get any more vivid, there appeared about 20 feet ahead of me an old woman, definitely at least 85, in a white pantsuit, wearing bright, perfectly applied coral lipstick. When I got close enough I read her name tag out loud in astonishment.

“Madelyn HELLING,” I said. Nevada City’s public library is the Madelyn Helling Library. “Oh my God. You’re Madelyn Helling—I—didn’t think she—you—was a real person.”

“Yes,” she said. “I know a lot of people think I am already dead, but I am not, for the time being.”

I did indeed think she was dead, and I admitted as much.

She laughed. You could tell she used to be really good looking. “People are always surprised to meet me!” she said. “Very surprised!” She said that she volunteered here and it was so wonderful to meet the people of Nevada County, or something like that.

K was behind me. “Oh my God! Madelyn Helling! I can’t—I can’t believe it! I mean, I—I didn’t—” K. faltered, as I had.

“It’s OK,” I said, “She already knows everyone thinks she’s already dead.”

“Yes,” said Madelyn Helling. “Yes.” We boarded the train to the sound of her laughter.

The narrow-gauge train was very small, almost like a combination between a cart and a train. I think they said it held 26 people. That seems about right. It was nicely maintained, with polished railings. It sat about six straight across, or five people and one Merle.

The guide—a white man in his 70s wearing a Hawaiian shirt—stood on the right side of the train, holding a microphone. It was hard to hear him because everyone was just blathering a lot, but I did get that this little ride would take us on just a few miles of track, through a campground, and then we’d come back.

He said some more stuff too. I didn’t hear that much of it because K. was telling me about her job, where she’d been injured recently. She was in remarkably good spirits for someone who’d been injured at work and was also in a fight to the death battle with her kid’s secretly authoritarian kindergarten teacher.

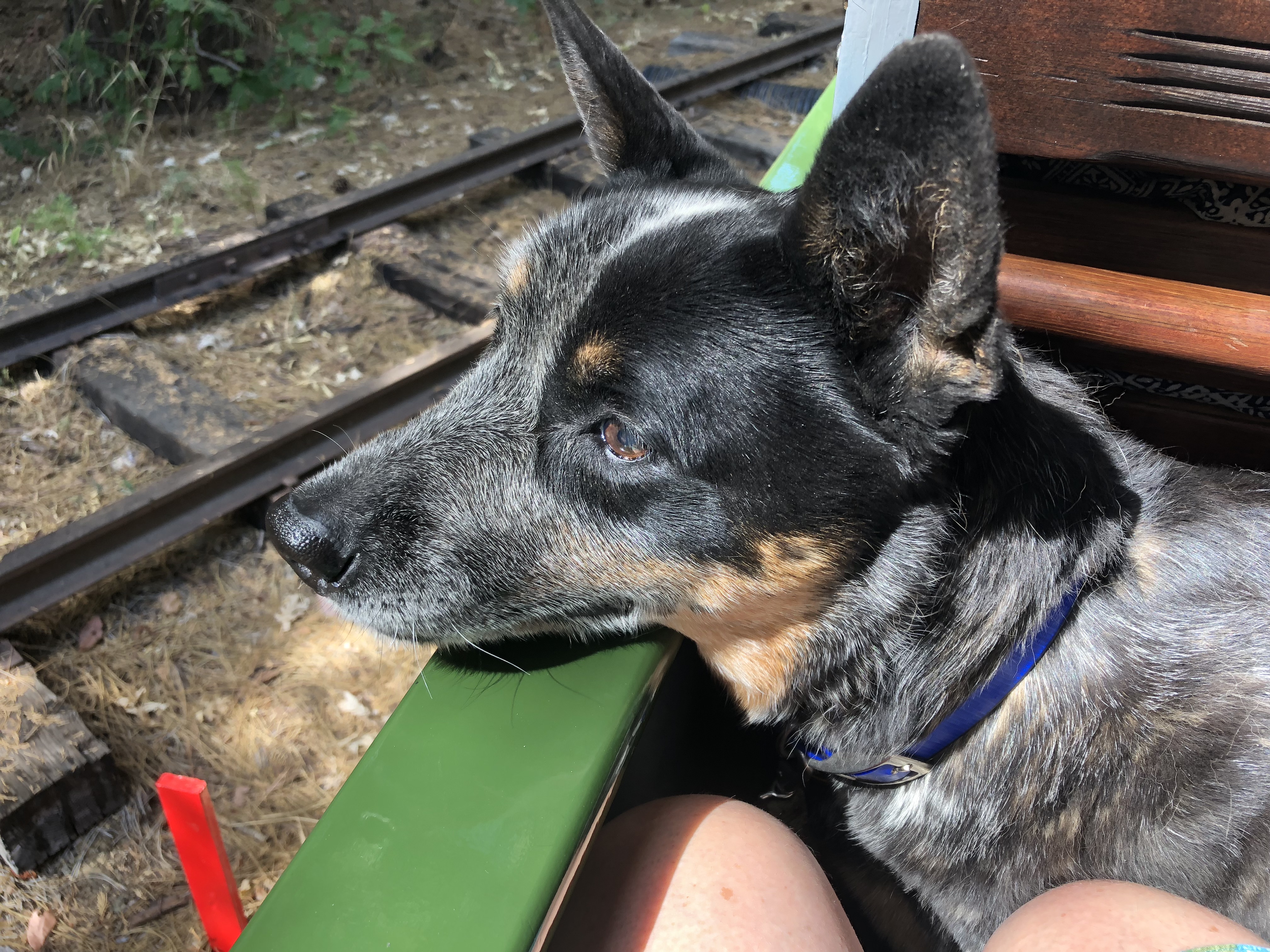

At first Merle was sitting up and looking at everyone and looking out at the passing scenery—really just blackberry bushes for the first few minutes of the journey—but then she just slumped onto the floor. I hate it when parents try to force their kids to experience things and I was not about to do this to Merle. If she did not want to pay attention, she did not have to.

There was a lull in the chatter and I was able to hear the announcer again. He told us about how the campground we were going through was aware there were two mine shafts on their property and they filled one of them in with cement. They couldn’t find the other one. “It’s a good thing no one on camping trips drinks,” the guide said. “That way no one will fall into it.” As we all laughed the train slowed down and then stopped. “You see that?” the announcer said. We all looked to the left, at a door built into the hillside, with a metal number 9 on it. In front of it was a little cart, like, well, like the little carts people take into gold mines.

“So this is a drift,” he said. “Does anyone know what a drift is?”

No one knew.

“Well,” the guy said, “A mine shaft goes straight into the ground, vertically. A drift goes into the hill sideways. Notice anything unusual about this particular drift?”

Everyone said they noticed it did not have any hinges or a doorknob.

“That’s right,” he said. “Because it’s not a REAL DRIFT.”

He let this sink in, and continued. “This isn’t a real drift,” he said again. “The campground put it in—as—well, sort of for fun, I guess.”

When the train started to move again, Merle suddenly got up and began behaving exactly the way you’d want a dog to behave on a train. She rested her head on the railing and looked out at the scenery going by, green, watered, campground grass, and a perfectly shaped willow tree and a Japanese maple. The air was soft and warm and Merle’s head was soft and warm under my hand. She doesn’t usually let me touch the top of her head but, perhaps knowing one might get a dog for the express purpose of resting one’s hand on their head while riding together on an old-fashioned train, today she made an exception.

L. told me the story of one of the train’s most famous crashes, in 1893. A circus had just performed in Grass Valley and was headed back to Colfax, and the first car was carrying horses—too many horses. Apparently one of the horses moved over to the other side of the train and the car went tumbling off the track, taking more cars with it. Some of those cars were filled with lions and bears, who were all rescued. Two people died.

When we got back to the station Madelyn Helling was sitting outside holding a little wooden train on her lap with a slot in the top. People were stuffing money into it. I put in five dollars. “Thank you,” she said. We started talking. She started talking, really. I had mistakenly thought that Madelyn Helling was just a rich benefactress. It turned out that no, she was the County Librarian for many years and at various points she had fought to get various percentages of sales tax earmarked for the library. The Nevada County libraries used to have a budget of something like $100,000 and now, she said, it was several million.

Then she started to talk about Andrew Carnegie, because although the newish (like 25 years old) Nevada City library was the Madelyn Helling Library, the older, more stately Grass Valley Library was a Carnegie library—one of the 1700 or so libraries he built all over the US (and another thousand or so around the world) between 1883 and 1929. “He had a special thing in his prenup with his wife about funding libraries, that she had to keep funding the libraries, to keep the libraries going,” Madelyn Helling said, her gaze so lovingly reverent I wondered if library holograms were sprouting up in her middle distance. “And he had special blueprints for libraries, and you know, you couldn’t deviate from them.” She wagged her finger as if she were Carnegie himself, admonishing a disobedient architect.

I wasn’t exactly sure whether she thought Andrew Carnegie was a great human being or kind of a pain in the ass. Feeling her out, I said, “Hmm, yeah it sounded like Andrew was a little uptight, maybe.”

Madelyn Helling said, “Oh, he was wonderful. Oh, if only we still had people like him now!” She closed her eyes against the hot autumn sun, smiling the way people who love Andrew Carnegie smile when they think about him, I guess. “Sometimes I pause in front of his portrait in the Grass Valley Library and I say, ‘Come back, Andrew. Come back!’ ”

“Sales tax,” L. muttered as we walked away. “Give me a fucking break. Why does everyone in this country love rich people so much? It’s weird.”

We caught up with everyone else. “I think we all have to agree Merle was a pretty good dog on that trip,” I said.

“No!” shouted Nelson. He stopped walking and put his arms around Merle, who looked uncomfortable but willing. “Merle was a very good dog.”

Sarah Miller