La Comédie humaine is the diary of American expatriate Claire Berlinski’s amazing journey onto the Parisian stage. (Names have been changed to protect privacy.) If you missed the Introduction, we urge you to begin from there.

I showed up precisely on time, on Wednesday evening, and kissed everyone enthusiastically. I’d met many of them before: Creepy Balthazar was there, wearing creepy leather trousers. Since I had not yet realized that demonstrable talent was not a requirement for taking the class, that puzzled me. He’d screwed up every exercise except the one where we were supposed to act stupid. Olivier—the Usain Bolt of French Speed-talking—had passed, as had Damien, this time in a jacket, rather than a cravat, that looked as if he’d borrowed it from his father. Dominique and Anne-Laure had of course passed, with their perfect 16th-arrondissement accents. The little dog with bulging eyes had passed; he was waiting just where I’d seen him last, interested in absolutely no one but Nathalie, whom he loved with a passion and loyalty so fierce he would barely suffer himself to be caressed by anyone else.

Oddly, Céleste wasn’t there: She had failed despite her perfect command of the virelangue. Nor was Solange. Nor was Martin. Nor was Alain: done in, I suppose, by his poor elocution.

Alas, Louise had passed, and what’s more, she showed up wearing a backless black cocktail dress that revealed her ballerina supraspinati and scapulae and her long, willowy legs; fringed and beaded earrings the color of champagne; a cluster of diamanté brooches piled in her messy, bed-head ombré strawberry blonde hair, and glittery “statement” heels, the statement, in her case, being, “I’m a bitch.” Anyone else wearing that outfit would have been ridiculously overdressed, but it looked perfectly normal on her, especially because she wore a denim jacket over it if to say, “Anyone else wearing this outfit would be ridiculously overdressed, but it looks perfectly normal on me. This is just the way I rush to my acting lessons after my cinq-à-sept with someone else’s husband.”

My brother was convinced that if I wrote a book about taking acting lessons in Paris it would sell instantly. As he pointed out, an American writer’s real market isn’t American readers, it’s Manhattan publishers. And every last one of them is a frustrated woman with artistic pretensions whose greatest fantasy is to live in Paris and do something … dramatic.

There were new people, too, whom I hadn’t seen before. I kissed Anouk, who had dimples and bangs and was professionally adorable. She was destined to play warm-hearted characters who teach us about the things in life that matter; about sincerity, tolerance, and the simple pleasures, all set in a traditional village in postwar France,where she would arrive with her illegitimate daughter and scandalize the locals by opening a small chocolaterie during Lent. Then she’d win over the dour and suspicious townspeople with her confections, her dimples, and her bangs.

I kissed Joséphine, an older, cranky woman whose last name probably begin with a “de,” as in, Madame de Laclos-Laforge, and whose ancestors had probably chased out all the Huguenots in their village.

Then a man with a particularly expressive face caught my eye: emotional, sharply angled, intense—the face of an actor who’d play a World War II flying ace. His hooded eyes, olive skin and almost regal bearing reminded me of Moghul paintings I’d seen in books, paintings of emperors and palace guards, scenes of royal intrigue. Clearly French, but I decided he must have some Mediterranean blood in his veins. He had deep lines around his eyes, as if he had spent years in the sun, and I could discern beneath his shirt the kind of lean musculature men develop when they work outdoors all day.

I suddenly felt self-conscious. My hair was clean, at least. I’d just washed it. I’d splashed out to celebrate passing my audition and bought myself a new blue T-shirt.

On the other hand, I told myself, I was here to make friends. I had passed an audition to become a comédienne at one of Paris’s oldest and most prestigious theaters. I had every right to introduce myself, and so I stood up straight, walked toward him with what I hoped was “a spirit of feminine grace,” kissed him on both cheeks, and addressed him as “tu.”

He did not kiss me back. He looked utterly appalled and embarrassed. He didn’t say anything.

But that did not make sense. I was wearing a clean T-shirt.

Perhaps some small talk would sort this out. “It’s my first class,” I said, blushing, hoping this explanation would excuse whatever faux pas I’d just committed. Might he be someone very famous, I asked myself? Was he here to give a master class? “How long have you been here?” I asked, figuring that was a question open-ended enough that it couldmean I fully understood his importance.

“Madame, I have been here since nine o’clock this morning. The toilet works again. For now. But I must counsel you: You must never again dispose of your feminine hygiene product in such a manner. Vous risquez d’endommager le système de plomberie de façon permanente.”

I suddenly noticed the tool box by his side, which he picked up. He strode out of the theater, clearly conveying his longing to put us all up against the wall come the Revolution.

Fabien clapped his hands. WHRROAKAY!

We began again with the shoulder rolling, the vowel shouting, and circling the room while creating gestes psychologiques.

He told us we were aggravated; thus we were aggravated; he told us we were supplicating, and we supplicated. Then he put the two exercises together by separating us into “bosses” and “employees.” The supplicants were to ask their bosses if they could have a few minutes of their time to discuss “the issue of a raise,” and the aggravated bosses were to say, “It’s not a good time.”

I felt like an old hand.

Then it was time to work on mime.

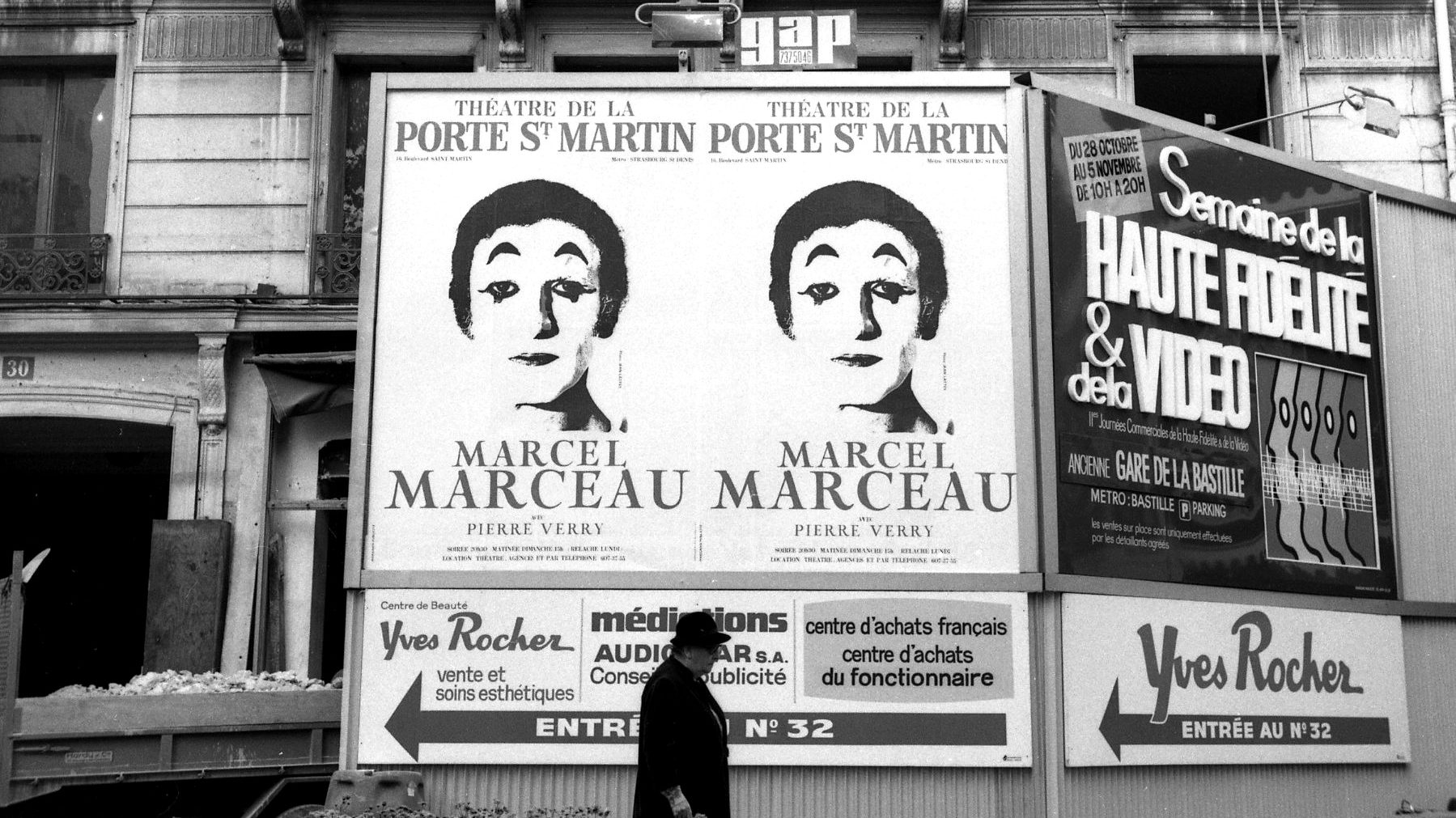

Anglos see mimes as low-prestige and annoying: not proper actors at all. You’ll see no focus on mime, say, at the Royal Central School for Speech and Drama. But when you think about it, why not? Wouldn’t actors benefit enormously from studying every gesture they make, and figuring out how to convince people they’re really making those gestures on stage?

Fabien stressed that performing on stage is not just “getting into the character.” Much of the work is technical—not least because because you have to project your voice clearly all the way to the farthest seats in the house, which for almost everyone means shouting at the top of your lungs. And if you want to make that sound anything but “angry,” you have to learn to shout at the top of your lungs in a bored way, a curious way, a lovelorn way, a cunning way, a scheming way, a flirtatious way—and none of that is remotely natural. It’s a technical skill. No matter how much I believe my sister is married to Stanley Kowalski, no one is going to hear me if I can’t manage to scream “I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers” all the way to the upstairs row of the theater—and no one is going to be moved if I scream it in what sounds like a furious or terrified way.

So yes, mime. We worked on this endlessly, because even the people in the balcony have to be able to see and understand what you’re doing, and if what you’re doing is, say, putting on your makeup, it has to be really clear from your hands and your body and your face that you’re putting on makeup while looking in a mirror, not just waving your hands in front of your face to swat away a wasp.

By the end of the class, I’d learned a whole new respect for mime and how precise and difficult a discipline it is. It’s hard. It’s a skill you have to learn by practicing; it takes hours of daily practice to be good at it. The masters of mime have my respect. I might even tip one of those guys in the subway someday. Because yes, mime is money—as we learned from Spinal Tap—but it is also a legitimate art. My journey to the savage heart of French culture was well underway.

We finished our series of mime exercises: “You are holding a ball,” said Fabien. Easy enough. “Now the ball is heavy. It’s getting heavier.” The ball got so heavy we could barely pick it up. Then it got lighter. Then it tried to float away like a balloon. Then we leaned against an imaginary wall. Then suddenly the wall collapsed. I don’t know what happens to you when the wall you’re leaning on collapses, but whenever it happens to me, I end up on the ground. So, obviously, I fell to the ground.

Everyone else staggered instead of falling. These innocents have no idea, I thought.

Then, to impress upon us the importance of interpretation physique, Fabien passed around the following text. I’ve translated it into English for you. Read it. What do you think is going on?

| –Excuse me, may I pass by? –No one passes! –Pardon? –We don’t pardon anymore. We kill! –You’ll let me pass, yes or … –Not without the password! –What’s the password? –I don’t have the right to tell you. Not even under torture. Military secret. –Listen, I pass here 36 times a day without a password. –That’s in the past. But no passing anymore. –And if I pass by force? –Force will respond to you. –Meaning? –Individuals who try to pass without a password are trespassing. –You’re nuts! –Yes. –And the enemy, who is he? –You don’t know who the enemy is? –Absolutely not. –But where do you live?! Where!!! –Down there, behind, at the dead end. –The enemy … he is everywhere. –Okay, I’m getting past or not? –Without a password: Negative. –Too bad. | –Pardon, je peux passer? –On passe pas! –Pardon? –On pardonne plus, on tue! –Vous me laissez passer oui ou … –Pas sans mot de passe! –C’est quoi le mot de passe? –Je n’ai pas le droit de vous le dire. Même sous le torture. Secret militaire. –Écoutez, je passe ici trente-six fois par jour sans mot de passe. –Ça passait, mais ça ne passe plus. –Et si je passe en force? –La force vous répondra. –C’est-à-dire? –Le quidam qui tente de passer sans mot de passe trépasse. –Vous êtes dingue! –Oui. –Et l’ennemi, c’est qui? –Vous ne savez pas qui est l’ennemi? –Absolument pas. –Mais où vivez-vous?! Où!!! –Là-bas, derrière, au bout de l’impasse. –L’ennemi, lui, est partout. –Bon, je passe ou pas? –Sans mot de passe: négatif. –Tant pis. |

Fabien separated us into groups of three—I was with Julien and Anne-Laure. He told us to spend fifteen minutes making up three completely different interpretations. They must involve entirely different characters, different places, times, contexts. “The words of the playwright must never change,” Julien said. Those were inviolate. But within the confines of those words, many things could happen—and figuring out what was happening was our job.

I will skip ahead and tell you the surprise at the end of this exercise. After we had discussed our interpretations, and decided which ones we liked best, Fabien told us to take turns performing our favorite.

The game was this: If the audience understood our interpretation,understood when, why, and how the dialogue transpired—and remember, every word had to make sense—we did it right.

If they didn’t get it, obviously, we didn’t.

You now have a week to think of three interpretations and how you would convey them. (We only had fifteen minutes.) I invite you to submit your best ideas to submissions@popula.com; I’ll be publishing the best ones here next week.

Tune in for the next episode of La Comédie Humaine to find out how we interpreted our text—and whether we passed.

So, readers may want to know: Did I make small talk afterward?

No, I didn’t.

By the end of our class, every week, making small talk at the end of it proved one of the hardest challenges for me to overcome. Once again, I slunk out, friendless.

Claire Berlinski, La Comédie humaine