In the discussion of Persian politics, especially on social media, the word “trowel” (ماله, or maale) comes up constantly. But it has nothing to do with laying bricks. A person accused of troweling (ماله کشی) is arraigned for arguing in favor of an objectionable political position without openly advocating for it, spreading a layer of acceptability over its contours. A troweler, as it goes, is a sly dissembler, a naïve conformist, a sugar-coater, an incurable optimist, or all the above. Troweling is not one specific method of fallacious argument, nor is it exclusive to apologist propaganda. It’s a word with a practically, and problematically, wide range of interpretation that can include any attempt, as it were, to put lipstick on a pig.

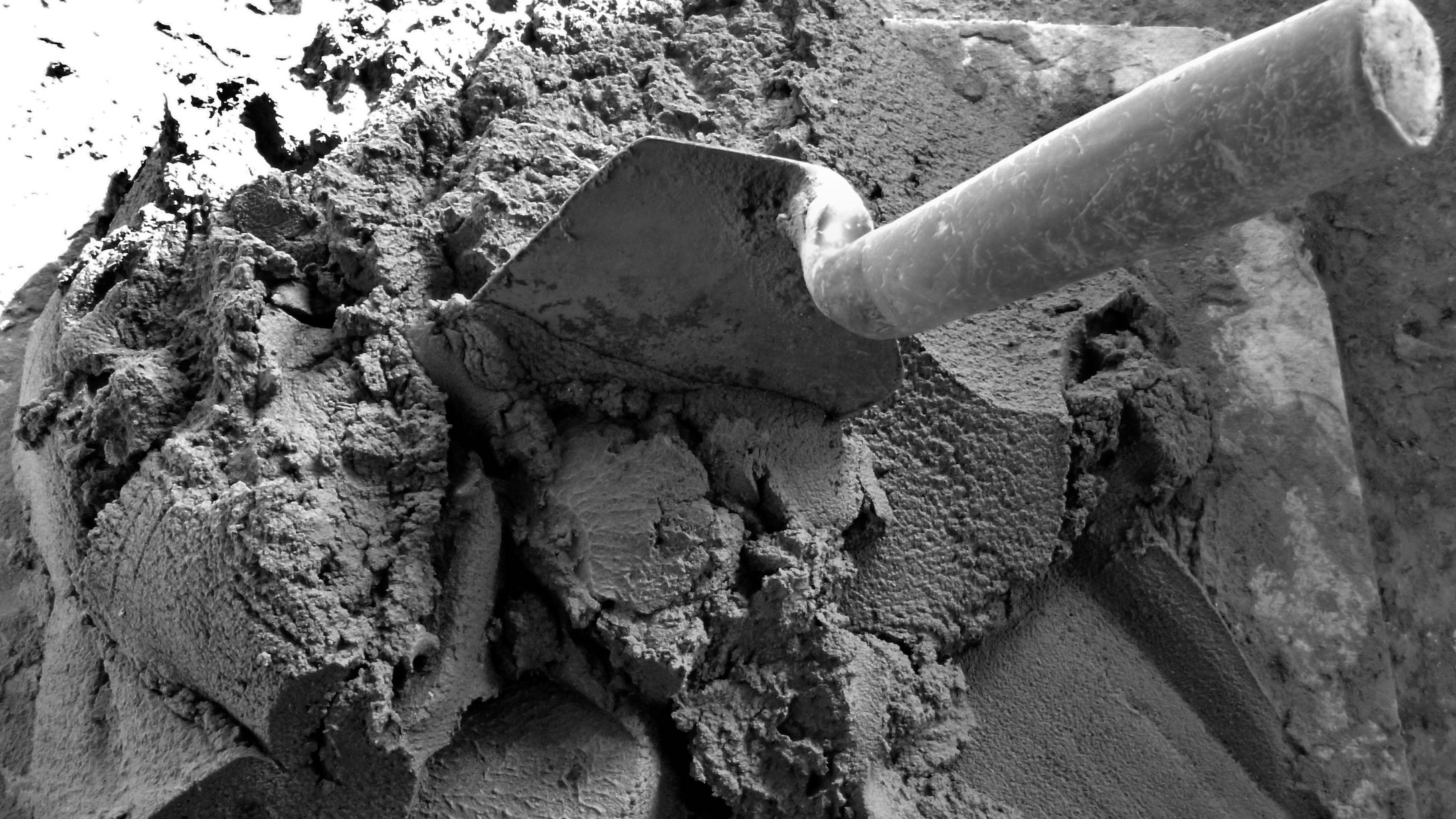

Like many hype idioms in the age of social media, the exact backstory of troweling is anyone’s guess, but its figurative meaning is readily apparent to Persian speakers. Just as an actual trowel is used to spread and smooth soil, mortar, or plaster, turning an amorphous clump into a neatly leveled plane, the figurative trowel includes a whole set of rhetorical tools to make an unpresentable policy presentable. If you notice a resemblance to another social media phrase, “troll,” you may be disappointed to learn that the original Persian phrase doesn’t carry the same connotation. There is also an underlying difference between a troll and a troweler: the former seeks attention through provocation, which may or may not reveal a genuine political or ethical conviction, but the latter tends to deflect unwanted attention, and could be the one calling for compromise and reticence. To take an American example, think of all those who plead that the immediate aftermath of a mass shooting is not the right time to talk about gun violence. That said, trolling can become one of the tactics a troweler uses in conversation, especially if cornered.

One who claims that, say, the unilateral reinstatement of economic sanctions on Iran by the Trump administration is somehow Iran’s own fault might be called a troweler for American foreign policy. If one shares a photo of the young Saudi Prince, Mohammad bin Salman, shaking hands with tech billionaires, donning a blazer and pair of jeans that are supposed to make him less regal and more business class, one could as well be branded a MbS troweler. Of course, like the word “resistance,” the meaning of trowel is dependent both on whom it refers to and who makes the reference. A labor activist could be condemned as troweling for communism (which she might take as an accolade rather than an insult), and a reporter covering the independence referendum in Kurdistan could be denounced for separatist troweling. Decoding why and how someone is accused of troweling can be ironically confusing, given that obfuscating the meaning of a term is itself one of many tactics in the trowel textbook.

In Iranian political lingo, trowel has mostly become a shorthand denoting apologism for Islamic Republic policies. A Twitter bot account (@Malekesh_bot) that automatically retweets anything with the term troweler (the Persian word is pronounced mall-eh-kesh, ergo the bot’s name) gives a good sense of its use. Most of the collected tweets use the phrase “state troweler,” which doesn’t necessarily mean one is hired for or in any way compensated by the government, but suggests a political sympathy with Iranian state. There are, nonetheless, plenty of examples of the term used in the opposite direction, to castigate whoever sides with Iran’s many international adversaries.

A straightforward defense of, for instance, Iran’s proxy war in Syria isn’t troweling, but a tranquil comment on the need for Iran to guarantee safe access to Shiite sacred shrines in Iraq could be read as state trowel, because it implicitly excuses Iranian meddling with a neighbor’s domestic affairs. You may have to divine a person’s intentions, or carefully examine the context of a claim, to deduce trowel, which is why calling out troweling can easily amount to crying wolf. That, in turn, could be called out by others as an attempt at trowel, ad infinitum.

The deep, inescapable sense of uncertainty regarding any kind of media coverage is perhaps the largest factor in the spread of this term. When a word, especially one with such a malleable meaning, catches on in a linguistic community, it means a vacuum was begging to be filled. The etymology of the term might remain a mystery, but the origin of the opening it now occupies is much less enigmatic: decades of state censorship, plus international isolation that impedes foreign reporters’ free access to Iran. This climate has made major broadcasting corporation coverage all but useless. The ubiquitous use of the stock photo “Woman in Chador Walks by Anti-US Mural” offers an example. Using stock photos is not unique to reports about Iran, but when it comes to Iranian news, stock photos are all one can find.

The Iranian public is not, of course, completely isolated from the rest of the world. Limitations on internet access, like banning Facebook and Twitter, have not quite worked. Most Iranians find their way in anyway. (The only popular social network not banned is Instagram, which is also the one without sharing options, and thus the least useful for broadcasting.) Iranians have adapted themselves to this limbo of media coverage, in which whatever official state organizations say is either outright fallacious or somehow doctored, and whatever comes from international agencies like Reuters or BBC (even if one naively assumes their impartiality) is to be taken with a grain of salt, because they simply don’t have a resident correspondent in the country.

This lack is supposedly redressed by an astonishing proliferation of unreliable news channels in Telegram, an encrypted messaging app that is notoriously hard to censor. These channels not only benefit from, and propagate, the paranoid reactions of their anxious audience, but also justify their lack of journalistic integrity by a show of oppositional daring: because reporters who don’t toe the line are playing with their lives, the reports in these channels are always anonymous, which then means they are also never properly edited, fact-checked, or in some cases even proofread. One of the most famous of these bootleg news channels is AmadNews, with almost 1.8 million followers.

If this phenomenon resembles fringe media outlets in America, like InfoWars, the main difference is in the matter of choice. Those who follow far-right American outlets mostly do so out of ideological conviction and not practical necessity. But for Iranian followers of popup news channels, it mostly boils down to the need for any news at all. It’s hard to argue against the belief that many events in the country wouldn’t get any coverage in the first place, had it not been for sporadic and error-ridden reports from bootleg news outlets. What makes matters worse is the presence of several channels, like Akharin Khabar (meaning “latest news”) that offer a crazy mix of almost every kind of media, from humorous Vine-style clips to updates on the dollar exchange rate, from product placement to parliamentary press coverage, all with a minimum level of editorial finesse. It is this bizarre jungle of cheap entertainment and simplified newscasting that keeps Akharin Khabar’s subscription rate at about 2.2 million.

Troweling becomes a viable concept in this hazy world of faux-journalism, because not only are the intentions and background of reporters left unknown, leaving room for all sorts of speculation, but also because in many cases it’s impossible to tell the difference between an honest mistake and propaganda is impossible to tell. Following the money makes it even more confusing. The alleged founder of AmadNews is Ruhollah Zam, an opponent of the Iranian state with a shady background, while Akharin Khabar is owned by an institution closely affiliated with Astan Quds, one of the organizations directly controlled by the Iranian Supreme Leader. The two channels couldn’t be further from each other in their political outlooks, as is obvious in their favorite topics, yet their style of news coverage is strikingly similar: provocative, tacky, and without much consideration for facts. An audience used to such media becomes simultaneously distrustful of and receptive to everything.

Suspicion of media is now a global pandemic, but the Iranian case is remarkably radical. Questioning the sources of any political publication has become less about factuality than a knee-jerk response to anything unpleasant. The main problem with the rhetoric of trowel is not that it can easily turn against itself, but that it showcases the helplessness of a dizzy audience in a world chock-full of news and yet devoid of trust. It doesn’t mean that calling out troweling is always a false claim, but that ubiquity of accusations of troweling is a phenomenon no less meaningful than troweling itself.

As some of its applications suggest, the concept of trowel extends beyond Iranian media. Troweling is, in a sense, what most pundits do on American cable news TV channels. The art of punditry is not too far from masonry. Given the crazy subject of the day, be it a new migration horror story, a porn-related presidential scandal, a voter fraud fiasco, or the First Lady’s wardrobe policy, pundits are summoned to offer, as the Sanskrit root “pandit” suggests, their wisdom. But what they do in practice is to take an absurd heap of suppositions and transform them into something resembling a coherent argument; in other words, to trowel the news. If Iranian troweling surfaces in the twilight of professional journalism, American media has managed to make troweling a full-time profession.