La Comédie humaine is the diary of American expatriate Claire Berlinski’s amazing journey onto the Parisian stage. (Names have been changed to protect privacy.) If you missed the Introduction, we urge you to begin from there.

—How’s it going?

—Are you shitting me?

—Hey, what’s wrong?

—What’s right?

—Are you seeing a shrink?

—I’m too anxious.

—Exactly.

—I’m on edge.

—Go see a shrink.

—You want me to tell my life story to some guy I don’t know and cough up cash?

—If it helps …

—Even when I’m sitting down I can’t rest.

—Exactly, lying down …

—No, no, no, no.

—Okay, don’t go.

—I’m burnt out, I’m telling you.

—Are you taking meds?

—It’s not me who needs them.

—Your husband?

—He’s taking them, thanks.

—And your kids?

—At the shrink three times a week, exactly on time.

—Oh, great, great.

—He nicks me for nine sessions, cash.

—If it helps them.

—It makes me nuts.

—Other than that?

—Since Christmas we’ve been eating organic.

—It’s healthier.

—Have you seen the prices?

—Health doesn’t have a price.

—That’s just the kind of bullshit that makes me nuts!

—Hey, do you have a problem?

—Me? A problem?

—With money?

—With money?

—That’s right.

—Why are you asking me that?

—I dunno, just said it like that.

—A problem with money, me?

—Think about it.

—Do I owe you something?

—No, no.

—I can’t accept it.

—I meant well.

—Wait, what do you want to ask me, exactly?

—Just how it’s going.

—That’s all?

—That’s all.

—It’s going fine, and you?

—We’re making do.

—Ciao.

—Bye.

Jean-Claude Grumberg, Ça va

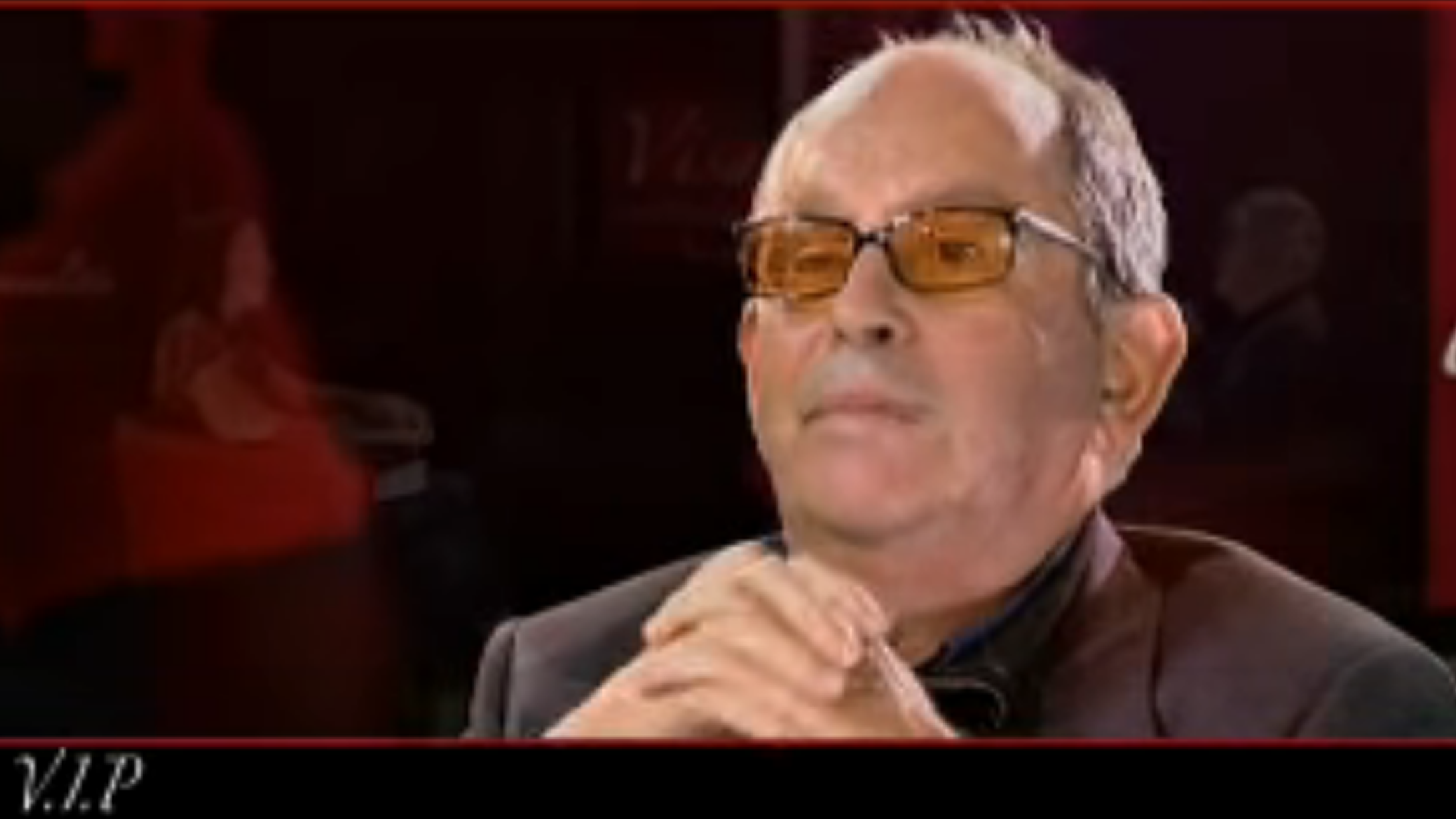

Jean-Claude Grumberg was born in 1939. His father was deported and murdered by the Nazis. Before becoming a playwright worked as a tailor. His other works are not comic. They are concerned with his father’s death in the camps. One is called, Mama is coming back, poor orphan. He co-wrote The Last Métro with Truffaut. He received the Grand Prize of the Académie française in 1991, and won the Molière Award for best playwright twice.

The scene we’d been assigned was from a book of Grumberg dialogues called Ça va. The French are nuts for Ça va. They think it’s “cruel and profound in its drôlerie.” It is supposedly reminiscent of Beckett and Ionesco. They claim it requires of the comédienne “une ironie dévastatrice.”

The idea is that there are 45 dialogues, all beginning with the question, “How are you?” “Ça va” is the casual way you ask that here, a cross between “How’s it going?” “How ya doing?” and “Dude!” and the typical answer is also “Ça va.” If your voice rises on the last syllable it’s the question, if it falls on that syllable it’s the answer, and the answer means “Fine,” or “Good,” or “Dude.” It’s what Eric Berne, the founder of the school of transactional analysis in psychotherapy calls a stroke: a semantically empty phrase that’s just meant to convey recognition—it’s a “unit of attention that provides stimulation to an individual.” If you live in France you’ll say “Ça va” dozens of times a day, often while mindlessly kissing your interlocutor’s cheeks: three units of attention.

The conceit of the play is that everyone takes the question seriously and tells his or her interlocutor how he or she is really doing. There are 45 dialogues, all variations on this theme—in the street, at a bus stop, at a cafe, in the hospital, among the dead. In mine, I ask my counterpart how it’s going and she totally flips her wig. (“Flipper sa race,” in French, make of that what you will: Americans flip their wigs; the French flip their phenotypes.) Then I urge her to go to a psychiatrist and suggest she take “meds.”

I wondered if Fabien had cast me in the role owing to my natural affinity for the character, but on reflection, I suspected not. He probably chose it because the language is simple, and there’s no incompatibility between the character and an American accent. He wanted to be sure I was able to pronounce all the words correctly. Fair enough.

The characters don’t have names. I’m –. Monique is –.

Fabien told us all to do a cold reading of our newly assigned texts. On the first reading, I mispronounced “psy.” In French, you pronounce the “p”, almost like “pshaw.” It’s short for “psychiatrist,” in which you also pronounce the “p,” so it’s Puh-seee-chee-uh-treeest and thus shortened to Puh-SEE in French, which is an initial consonant cluster that we simply don’t have in English. We just don’t. But because it looks just like the English word, it tripped me up every time. I kept getting confused and thinking, “Okay, I know this word has a weird pronunciation. But which way is it weird? Which is the weird English way and which is the weird French way?” I developed such a complex about it that someone, I’m sure, considered advising me to see a psy about it.

But I’m proud to say I can now say, “Go see a shrink” almost as a Parisian would:

Otherwise, the first reading went fine: we got a “très bien” from Fabien. To my surprise, the class laughed—a lot—at the presumptive punchlines. I wasn’t trying to make them laugh. I was just focusing on pronouncing everything correctly. But they seemed to find this text inherently comedic, and they weren’t just being polite. I knew this because they’d been chattering—rudely—through everyone else’s readings, to the point of making me irritable. For some reason, though, this dialogue—or my inherently hilarious accent—made them laugh.

I went home and watched every version I could find on YouTube. None of them made me laugh.

Does that make you laugh?

If I could figure out why French people find this play so hilarious, I reckoned, I’d understand the French soul in a way no American has before. Perhaps I’d even solve the most enduring mystery of all: why the French love Jerry Lewis. (He has been replaced in French comedy lore by Donald Trump, by the way. The very name “Donald Trump” incites genuine tears of laughter. You can barely finish saying it—Donald Truhhh …—and they start laughing until they’re shaking like jello and they just can’t stop, they tell you they haven’t laughed like that since they were petit fils or petite filles watching Jerry Lewis. They think electing him was an American stroke of comedic genius. And no, they’re not chanting “We want Trump” in the streets. They couldn’t. They’d collapse in hysterics before they finished the sentence.)

At first I couldn’t make sense of the text—I mean, I could, literally, but I just could not understand why Grumberg is considered a great playwright. But the more I studied it, the more I realized that in fact, he’s very witty. This isn’t the scene I’d have chosen to show you why—the one about the password was—but this was the scene we got.

Once again, my brother and my nephew helped me through the next stage of my acting career. They came to visit that week, and in between our excursions to the Virtual Reality theater (which ontologically blew my mind and made me seriously wonder, for the first time, if maybe I was just a brain in a vat) and the fly yoga studio, he helped me work out the characters’ whole backstories. We tried lots of different interpretations. If you like, you can try to figure out an interpretation before I tell you which one we settled on.

We spent days reciting the text to each other, to the point there was a really serious chance that some hapless bakery lady would ask us how we were and one of us—or worse, both of us—would shout, “Tu te fous de ma gueule?” We had to really work hard to make sure Leo understood he shouldn’t say that, even though we couldn’t stop saying it in public, either.

Finally, we decided that — and — are old friends. They work in the same building by the park. So they run into each other a lot when the weather is nice and people come out the park on their lunch break. From now on I’ll call Monique’s character “Monique’s character,” because otherwise you might confuse them. (Later, when you know the characters like you know your own face, you won’t believe you thought that, but I was once a beginner too, so I understand.) Anyway, Monique’s character—who’s a “she,” by the way; Fabien told us just to adapt it—always has problems, and my character gets a little sick of hearing about them. She’s getting a bitter divorce, and has been since forever. Her husband is driving her fucking crazy. The kids are acting out. The older one pulled a knife on one of his schoolmates, the middle one has an eating disorder, and the youngest one is biting his nails compulsively.

She just got off the phone after having a huge fight about money and the kids with her STBX: He seems to think you can earn a living by playing video games all day; they’ve got three kids with obvious problems, which is his fucking fault because they need a father—a reliable one—in the house, but instead they’ve got an overgrown teenager. She’s been telling him he needs to get a job, she can’t be the only one with a job in this family; and on top of it he’s scolding her because when he last dropped the kids off he saw that there were prepackaged microwave oven meals in the fridge. He thinks the kids should eat proper meals, only organic—as if that were their biggest worry! I mean, is he fucking out of his mind? Doesn’t he realize Josette just barfs up everything we feed her anyway? Has he even noticed that? No wonder the kids are a mess.

I’ve just come to the park to relax and read a dumb celebrity magazine for a bit on my lunch break. A Royal Wedding special, with bonus gossip from palace insiders about how Kate and Meghan secretly hate each other. I need a little down time from the stress at the office, and the last thing I want to hear is the latest episode in her deranged family saga; it’s been like this now for years, so basically I care, but I don’t.

By the next week, I’d memorized my lines cold, and I had it really well worked out. I felt so prepared, so pleased when I went to class the next week. Here’s a link to me reading the dialogue. Except you’ll notice I forgot one important thing. That’s not how you’re supposed to do it. Because it’s a dialogue. You know that cliché about it taking two to tango? Apparently, this is also true of dialogues.

Claire Berlinski