In third grade, I didn’t know the difference between a nose job and a blow job. I went to a Jewish school so nose jobs were as weird a concept and as common a practice. Blow jobs are for boys and nose jobs are for girls, I learned.

But I wanted a blow job! Not fair.

I was angry.

In second grade, I experimented with hate mail. We didn’t have the internet so I couldn’t troll. Plus, I was only seven and I needed help, so I roped in a friend to inscribe condemnations on wide-ruled loose-leaf, one handwritten note for every cubby. “I hat you,” each said. We didn’t know how to spell “hate,” so everybody got a hat. Hat mail.

I was angry, even before that.

In kindergarten, the teacher called my mom. “I’m concerned about Deenah because she only colors with the black crayon.” I was goth, too.

My mom was doing the best she could. She was in medical school when my parents had me, two years before they had my brother Reuben, who died from an accident at home when he was just 18 months old. I was three, and my mom was seven months pregnant with my brother Asher. By the time I was four, my parents had had two children, then one child, then two children again.

I used to say that I got to be an only child “twice.”

My mom became a child psychiatrist, and started a private practice.

The cobbler’s kids go barefoot, we joked. I knew this was funny from a very young age. Except it’s not totally true. We did go to therapy, so much therapy, but we were still barefoot in our own way.

I threw the tampons I found in her bathroom drawer out the window after running them under the faucet.

I drew a face on my butt in Crayola markers and mooned the few cars, our immediate neighbors probably, driving up our short, ten-house cul-de-sac. Ha-ha-ha!

My younger brother, Asher, was my victim. Asher, eat these ants, they’re chocolate! Asher, drink this open can of Coke that’s been sitting inside a tree overnight. Ha-ha-ha!

What a beautiful boy and girl you have, people told my mom. Me, scowling, with short hair in a Ninja Turtle t-shirt. Asher with long, beautiful blonde curls. Our family was mixed up from the beginning, and people let us know.

I never wore skirts or dresses, only giant t-shirts tucked into giant shorts worn high on my waist. My mom had to bribe me to wear a skirt to a wedding. She told me we would get a cat if I did. That’s the only memory I have of her trying to make me wear something I didn’t want to wear. I wore it. We never got a cat.

When I was five, I went on a Disney cruise with my grandparents. There would be some nice dinners and I would need to dress up. No, I wouldn’t wear a dress. No way. I wore a suit instead, proudly. In a red clip-on tie, I looked like a little republican.

Are you a boy or a girl? Are you a lesbian? Kids asked me at school. I felt shy when my jeans would bunch up in the crotch and I worried people would think I had a penis. I was always flattening the fabric. I wanted to be a boy then, yes, but I also cared what everybody thought. I’m a girl, I said. Fuck you.

This was the ‘90s, so people cared. They needed to know!

And I loved boys. That’s probably why I wanted to be one. I’ve been confused my whole life about the difference between the person you want to be with and the person you want to be.

I was also afraid people would call me Deenis as a nickname because it rhymed with penis. They didn’t, but I thought people were moments away from figuring out that they could.

At home, I had an invisible friend named Ryan. Ryan was cool. Ryan wore a backwards baseball cap, “No Fear” t-shirts, said “fuck” a lot and drew pictures of dicks and boobs. I said Ryan was my invisible friend, but I knew that Ryan was my alter ego.

I didn’t think this at the time, but my wish to be a boy might have had something to do with Reuben, my brother who died after accidentally strangling himself with the cord that adjusts the blinds. The tragedy precipitated my parents’ divorce and my mom’s depression, which became workaholism. If I was a boy, maybe I could be the boy my mom lost and my mom would be happy or work less.

She worked very early in the morning, until very late at night. School began at 8am, but she dropped Asher and me off at 6:50 or 7, before most teachers and administrators arrived.

This was the perfect time for stealing Hello Kitty pencils and erasers from the other kids’ desks. This was the perfect time for squeezing the gooey, pink bathroom soap all over the floor and skating around the tile like a hockey player. This was also the perfect time for etching “DV was here” on secret surfaces in the playground.

At this Reform Jewish school at a temple in Bel-Air, we wore blue and white uniforms. We studied Hebrew, but I never learned it. We had mandatory prayer services, but I tried to spend as much of those in the bathroom as possible.

We weren’t allowed to dress up for Halloween at school—that pagan holiday—but we did dress up for Purim. In fifth grade, I decided to go as a drug dealer and I brought Ziploc bags of Tic Tacs to school. I spent hours in class erasing a green eraser and collecting the shavings into a baggy. Marijuana. When the teachers found out, they said I couldn’t be a drug dealer for Purim, but I could be a gangster so I went as a gangster. “Gangsta’s Paradise” was my favorite song and I knew all the words.

One time in Jewish studies class, we were learning about a belief that when a candle is blown out, an angel dies. I was already in trouble for some reason and sitting at the teacher’s desk. When the teacher blew out the candle, I fell to the floor, feigning death. I was sent to the principal’s office.

Because I went to a weekly support group for kids with divorced parents, I was familiar with the administrative buildings and the guidance counselor. They were also familiar with my brother, who didn’t act out so much, he just went to sleep under his desk when he got tired or bored and one time, when he was seven years old, tried to leave school by simply walking away from it. The guidance counselor picked him up on Mulholland Drive. They found a map that I, the wise sixth-grader and protective older sister, drew to help him find his way home. Home was only two miles away. Never mind that Mulholland Dr. didn’t have sidewalks. Run free, little brother. He was the first first-grader suspended in the school’s history.

Later that year, something happened and I was less angry. It was called puberty. I grew my hair a little longer.

In seventh grade, I made friends for the first time with kids who liked doing the things I liked to do, like shopping for vintage bowling shirts and polyester plaid pants at Jet Rag and listening to Everclear.

Bar and bat mitzvahs happened every weekend. I wore skirts for the first time since that wedding when my mom promised me a cat, now because I wanted to.

I still refused to wear dress shoes of any kind and wore my beat-up sneakers to all the bar and bat mitzvahs. A girl at school told me she loved how I always chose comfort over beauty.

I reclaimed the name Deenis because we broadcast our insecurities so it seems like we don’t have them. Deenis was part of a duo with my friend Penny, who went by Penis. We were Penis and Deenis. I had the name airbrushed on a duffle bag along with an image of the anarchy sign by a vendor hired at a bar mitzvah.

For my own bat mitzvah, I didn’t choose classic themes like swing dancing or basketball like the other kids. Mine was “Dogs Driving Cars,” a combination of my two favorite things: dogs and cars. Each table had an airbrushed centerpiece (airbrushing was really “in”) of a Hanna-Barbera-style dog driving a classic car, and over the dance floor hung my name written in cursive on an airbrushed foamcore bone. I have always been pretty good at doing my own thing.

As I got older, the girls got more nose jobs and the boys got more blow jobs, but I got neither. To this day, I have never worn heels, I still shop in the men’s section, and up until pretty recently, I kept my hair short.

Sometimes I wonder what my childhood would have been like if I didn’t go to a private Jewish school, if my brother did not die, or if I grew up today when, at least in liberal communities in California, being trans is accepted. I never wanted to change my gender, but I did want to be a badass, to be different. I probably would have found other ways to act out. I’m no longer angry, perhaps to a fault. But Ryan still lives inside me, and Deenis, too, but please don’t call me that.

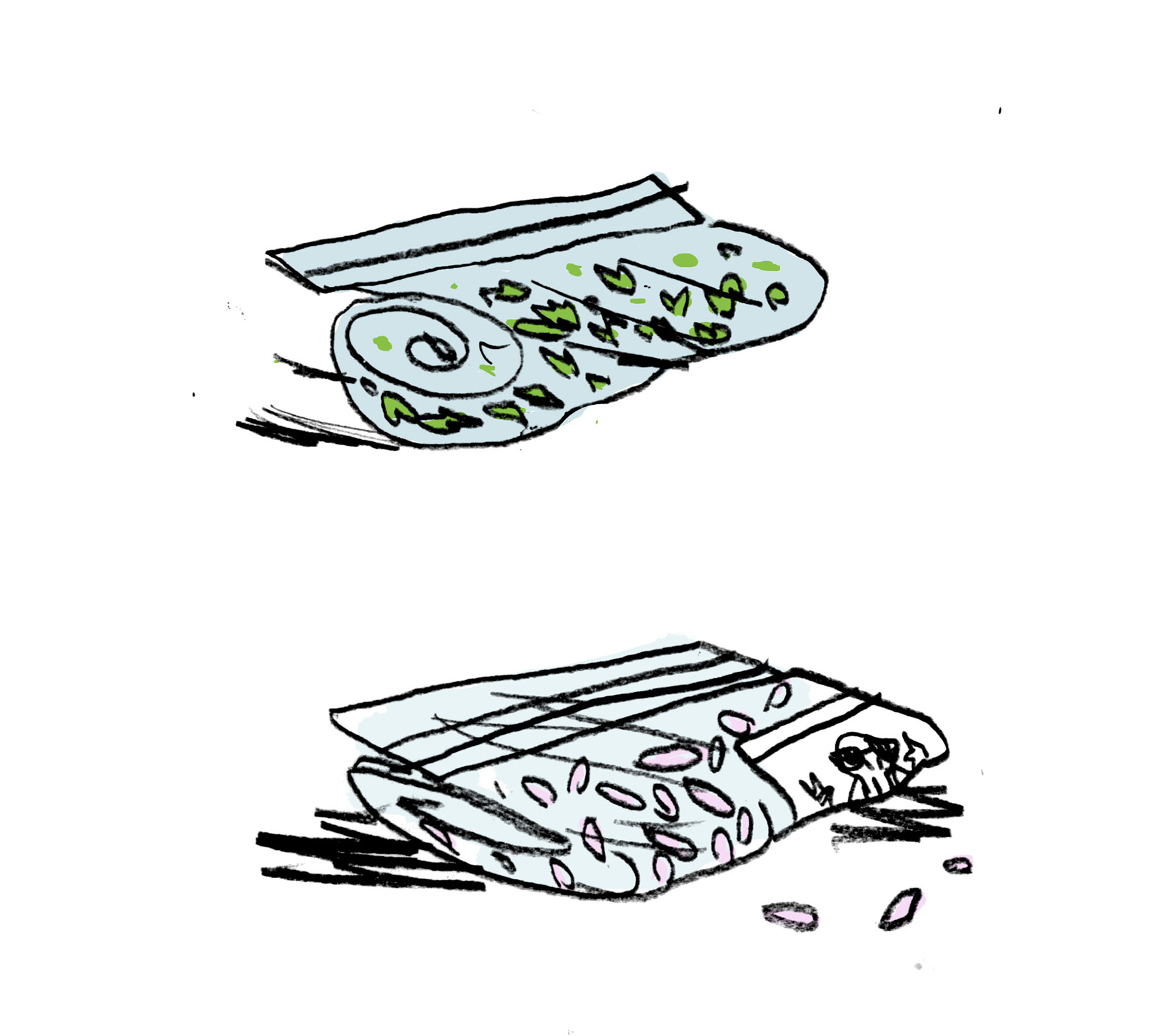

Illustrated essay, gender, anger, Judaism, identity, Deenah Vollmer, Sara Lautman