Google announced in 2007 that it intended to photograph every street in the world. By 2017, 10 million miles had been captured and meshed into the strange sphere of Google Street View, a panoramic display of stitched images that allows you to virtually trawl through Cincinnati or Christmas Island. You can go inside some businesses; in select locations, you can go underwater. You can zoom in on your childhood home, and you might even see a familiar car parked outside.

Street View is uncanny. The detail and precision with which Google has compiled billions of records and stitched them together is startling, especially when we look at familiar places. It can function as a lo-fi time machine, allowing you to view the same street in San Francisco over the course of 10 years. You can slowly slide a bar and watch as scaffolding goes up and comes down; a tree grows taller and then disappears; a parked truck leaves and never comes back; the light changes slowly.

Street View isn’t a seamless experience. It jumps through the images a bit too quickly and swivels around in a dizzying way. Something about the perspective is always slightly off,so you feel like you’re looking at a warped and manipulated world, which of course you are.

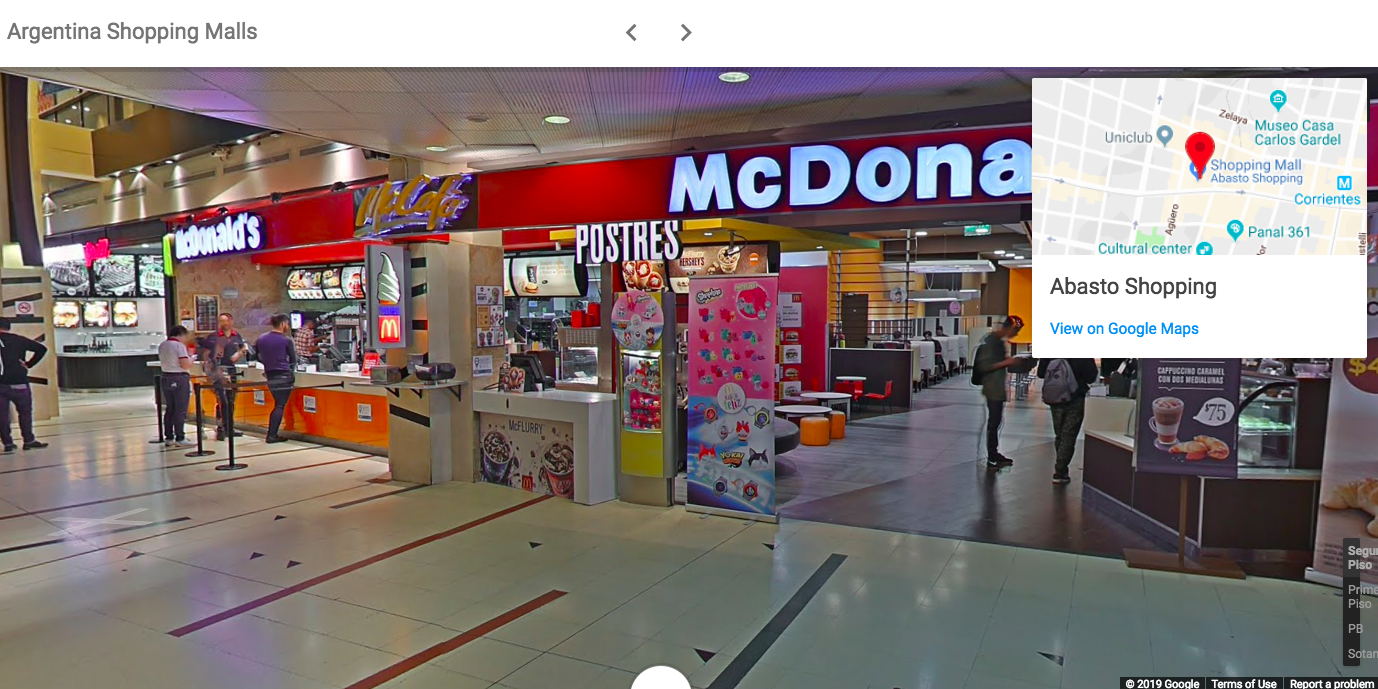

The manipulation is most obvious when people appear in Street View, which they often do, because city streets have people on them. Google uses an algorithm to blur faces, which adds a surreal quality. The blur isn’t perfect, either, so a person’s arm will be truncated, or two people will kind of smear together. From behind, bodies are left whole; you can scrutinize the line at a McCafé in a mall in Buenos Aires and perhaps recognize the back of someone’s head.

The blur is an attempt to preserve people’s privacy, or at least a way for people to continue to feel like they can walk down the street without ending up stuck like a fly in the amber of a public database. (In parts of the world, this is not true to begin with.) The imperfections of the blur expose how faux this privacy actually is. Faces of pedestrians might be hazy, but the sheer volume of information packed into a single street is overwhelming: addresses, homes, cars, slices of lives. As a reporter, I’ve used Street View as a tool for tracking people down in neighborhoods where crimes happened. If you have one address, you can use Street View to find the addresses of homes on the same block, and then run those addresses for names and phone numbers. “Hello,” I remember saying, to a startled older man who picked up his landline. “Were you at home at nine p.m. last night? Did you hear gunshots?” Indeed, he had.

Which is to say that although people are blurred, omitted, and chopped up in Street View, they are a constant and strange undercurrent to its manufactured world. After all, we look at Street View because we are interested in where other people are, or where other people are not. Looking at remote places is awe-inspiring: How did Google even get there?

The answer is that most of the time, people went there. Though Street View incorporates satellite pictures, more often than not, the photos were taken by people driving cars through cities. In recent years, Google has also employed trekkers, sailors, bikers, and snowmobilers in the quasi-insane quest to get the whole world on camera. But still, most often, it’s drivers.

The cars of Google Street View drivers are highly visible because of the mounted camera equipment and Google branding on the outsides; one Google Street View driver described their car as “a moving billboard” in an anonymous interview, and said they were harassed by people trying to get on camera. (Contrary perhaps to Google’s expectations, many Americans would love to be unblurred in Google’s record of the world.)

Like the majority of laborers employed by technopolies, the drivers are usually invisible. It’s hard to even find out much about the driving jobs; they aren’t always advertised directly and tend to come through temp agencies. Salary estimates online range from $14–$17 dollars per hour in the United States for short-term contracts. The drivers’ job is to drive around; meanwhile, Google’s 360-degree cameras take photos at an unbelievable rate. The photos are later assembled and processed and stitched, and people’s faces are blurred algorithmically.

Something interesting sometimes happens, though, a kind of rupture in the fabric of the Street View universe: the drivers’ faces appear, warped but not blurred, accidentally photographed as they adjust their cameras. Artist and researcher Emilio Vavarella searched Street View for these instances, and it became part of his work “Google Trilogy.” The series, “The Driver and The Cameras,” is currently on view in the Photographers’ Gallery in London.

Emilio Vavarella, THE GOOGLE TRILOGY – 3.The Driver and the Cameras (2012). Courtesy the artist.

Emilio Vavarella, THE GOOGLE TRILOGY – 3.The Driver and the Cameras (2012). Courtesy the artist.The effect of the photos Vavarella compiled is totally bizarre; the drivers’ faces are often cut in half, fading out into the familiar stereoscopic view of the world. In one, you can clearly see the driver’s face next to the blurred faces of sunbathers. It’s like watching the fantasy of Street View being peeled back. A revelation: it’s not actually you that’s walking on the street in Camden, Maine, or Zagreb. It’s someone else.

Vavarella’s photographs are effective because—to borrow the tech buzzword—they disrupt our understanding. Similarly, artist Benjamin Shaykin compiled a series of photos of hands that accidentally made it into the pages of Google Books during the scanning process. It’s almost evidentiary: look at these human bodies, involved in digitizing things. It pulls back the veil.

Emilio Vavarella, THE GOOGLE TRILOGY – 3.The Driver and the Cameras (2012). Courtesy the artist.

Emilio Vavarella, THE GOOGLE TRILOGY – 3.The Driver and the Cameras (2012). Courtesy the artist.I’ve spent a few hours on Street View, wondering if I’d see any drivers’ faces, but I didn’t. The virtual world remained both whole and unreal. The faces in San Francisco and Boston and Buenos Aires and Cincinnati were gently, imperfectly blurred.

Vavarella’s work leaves you wondering about the drivers. In the anonymous interview, the driver said that the job is basically like all jobs, “Anything you do every day eventually gets boring. Traffic sucks of course,” he said. “And breaks and rest stops are whenever. As long as the data gets collected, that’s all that matters.”