Panda bears are on the verge of extinction, but encouraging them to reproduce in captivity has proved notoriously difficult. Most famously, researchers have taken to filming “panda porn” in an effort to stimulate arousal; other efforts have included the use of Viagra, communication studies to learn how pandas attract mates in the wild, attempts at panda “speed dating,” and even the contemplation of panda cloning.

Science’s best efforts have largely been frustrated by captive panda bears’ apparent lack of interest in reproduction. Because pandas in the wild gather in groups for breeding activity, it is nearly impossible to recreate normal breeding conditions in captivity.

On the bright side, progress has been made on increasing panda bear numbers, with a 2014 census suggesting that there are 1,800 pandas in the wild today when, in the 1970s, there were just over 1,000 pandas in the wild. Just over 500 pandas remain in captivity.

But concerns remain about the effects of human development on wild pandas’ natural habitats, which could still disperse populations in a manner that prevents reproduction. Consequently the long-term outlook for the panda bear remains grim.

Would the panda bear exist at all today without human intervention?

Consider the possibility that the panda is in fact a creature not of life, but of death. An undead creature, in the sense that they would passed away long ago if not for human intervention; or at least a creature between life and death.

After all, these technological efforts to stimulate panda bear reproduction seem rather monstrous.

What lies beneath the panda bear’s cute exterior, as it appears within a zoo? Foucault might have termed it biopolitics, the politics of life and over life. Or maybe we should be talking about the cyborg panda, the panda that would not exist but for technological aids to reproduction.

Perhaps because of the grotesqueness of humanity’s efforts to keep panda bears alive, there is no shortage of op-eds specifically calling for pandas to be allowed to go extinct. They argue that pandas are a needless drain on economic resources, ask why we specifically care about saving pandas versus other animals, and suggest that panda extinction is merely natural selection at work. Articles have even been written about how to argue against those who advocate for the extinction of panda bears.

But if it is anchored to life solely through human intervention, the survival of the panda bear is tethered even more specifically to state intervention, namely that of the modern Chinese state. The majority of the world’s surviving pandas are in China; the Chinese government often gives pandas to other countries as a diplomatic treat.

Pandas were given as gifts in imperial times; gifts of exotic animals to and from royalty were made at various points throughout imperial Chinese history. It’s possible that certain Chinese mythological creatures sprang from such real-life gifts; some believe that the legend of the “qilin” (麒麟) originated from giraffes brought to China during antiquity.

“Panda bear diplomacy” as we know it today was originally conducted between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and western nations, particularly the United States.

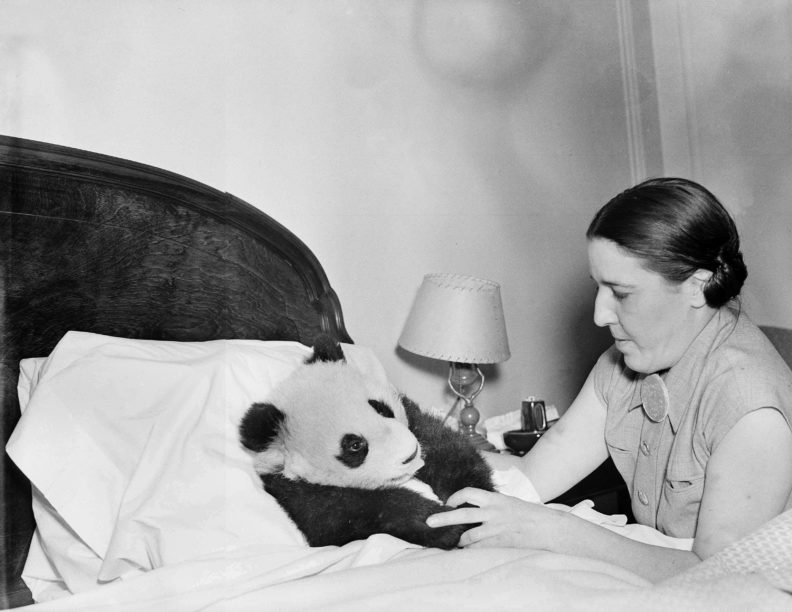

Though there is no shortage of contemporary examples—Kung Fu Panda comes to mind—the western craze for panda bears had set in by the early to mid-20th century, particularly in America and the UK. The sons of American president Theodore Roosevelt led an expedition to China to hunt a panda bear in the 1920s. American adventurer and socialite Ruth Harkness traveled to China in 1936, with the aim of smuggling a live panda bear back to America, the story of which became a popular sensation.

Capitalizing on this craze, Chiang Kai-shek, who was then still in control of the Chinese mainland, gave a pair of pandas to the United States in 1941. After Chiang Kai-Shek and the Kuomintang fled to Taiwan, their PRC successors also realized that pandas were a very useful tool for what we would refer today as “soft power,” sending their first pandas abroad as gifts in 1958.

But it would be a long while before the Chinese government would achieve an awareness of the need for environmental protections of any kind. 1958 marked the debut of the “Great Leap Forward,” which aimed to encourage the rapid industrialization and modernization of China. As the mass destruction of the environment caused by the Great Leap Forward amply demonstrates, the environmental costs of “progress” were not well understood in the early days of the PRC.

This was particularly true with respect to animal life. Mao’s “Four Pests Campaign,” which also began in 1958, called for the wholesale eradication of rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows from China (sparrows were replaced with bedbugs in 1960). After this campaign (and only then) it became evident that eradicating rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows would have a wide-ranging ecological impact in China.

Growing awareness of environmental damage and the possibility of extinction led China to stop giving panda bears as gifts in 1982. But the practice resumed just two years later, with China imposing fees on future panda loans, in line with what some saw as an increasing embrace of free-market principles during the Deng period. This has continued to the present.

Pandas are often given as gifts by China to other countries, including former enemies, as a gesture of peace and friendship.

For example, shortly after Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in February 1972, China gave two panda bears to America—Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, arguably the two most famous panda bears in history. Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing subsequently lived in the National Zoo in Washington DC for the next two decades; Ling-Ling died of heart failure in 1992, and Hsing-Hsing in 1999, after kidney failure. Most panda bears sent abroad have followed the naming pattern of Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, of having a name which consists of one character in their name repeated twice, as is sometimes done with Chinese nicknames.

At times panda bears have found themselves at the center of unusual political controversies.

In Taiwan, after the 2008 presidential victory of Ma Ying-jeou of the pro-unification Kuomintang in Taiwan, China gave two panda bears to Taiwan. The bears were named “Tuan Tuan” (團團) and “Yuan Yuan” (圓圓), derived from that “Tuanyuan” means “reunification” in Chinese (團圓).

After the presidential victory of Tsai Ing-wen of the historically pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party in 2016, rumors began circulating on the Internet that Tuan Tuan had spontaneously died in the Taipei Zoo—reminiscent of how, in ancient Chinese history, the sudden death of a mythical creature is seen as an ominous portent. These rumors were later proven to be false.

After the disappearance of flight MH370 in 2014, as a means of applying pressure to Malaysia to speed up its investigation of the plane’s disappearance, China delayed shipping two panda bears slated to be on loan to a zoo in Kuala Lumpur.

Japan—a country with longstanding antagonism toward China—has also hosted panda bears since 1972, after a visit to China by Japanese prime minister Tanaka Kakuei, sparking a panda craze in Japan.

It was in this context that Studio Ghibli founders Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki’s early work, Panda! Go, Panda! was released in Japan in 1972. Ueno Zoo resident panda Shin Shin has inspired such a devoted following that a man who has taken a photo of Shin Shin every day for seven years has become a viral phenomenon.

Tensions have been on the rise in recent years between an increasingly aggressive China and a Japan currently led by right-wing nationalists nostalgic for the era of the Japanese empire. Among the many issues contested between China and Japan are who owns the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands in the South China Sea: The dispute led then-Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara, a well-known right-wing nationalist and former avant-garde novelist, to suggest that a newborn panda bear born to Shin Shin be named “Sen Sen” or “Kaku Kaku.” But, perhaps too pure for this world, the panda cub died before it could be named.

Panda bears are much beloved even in countries with ambivalent political relationships with China, such as Taiwan and Japan. Remarkably, “panda bear diplomacy” really works to defuse political tensions for the Chinese government; the cuteness of the panda and public adulation creates a sort of “anti-politics,” perhaps, neutralizing the concerns that one might otherwise have about the politics of the Chinese party-state..

Indeed, I remember that after Tuan Tuan and Yuan Yuan gave birth to a cub, who was named “Yuanzai” (圓仔), meaning “round thing”, every screen in every MRT station in Taipei was showing how long the current line to see Yuanzai was. Undeniably the panda was cute, but I thought it absurd for a city of 2.7 million to be subjected to this in every metro station.

Pandas have also become quite a lucrative industry. They are loaned on ten-year terms, with the requirement that one million USD be paid to the Chinese government each year during the loan period. Afterward, the pandas must generally be returned to China, along with any cubs they may have had, even the cubs being considered the property of the Chinese government. Given the stiff fees, the Chinese government’s panda breeding programs have been accused of being mere “panda mills” aimed at the production of as many pandas for international loan as possible, rather than an attempt to ensure the long-term sustainability of the species.

The Chinese government has lashed out against suggestions that the panda should be downgraded from its current endangered status, which suggests that it may be more useful for their purposes if the panda bear remains endangered. Endangered status ensures that the panda bear will remain a sympathetic animal to the international world. Or maybe the Chinese government wants to make sure that pandas are considered a rare and thus valuable commodity.

Attempts to encourage panda reproduction are roughly comparable to the Chinese government’s attempts to persuade young people to have more children in an era in which China faces an increasingly aged and declining population. It’s a demographic time bomb common in East Asia—Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea are in a similar position—but China’s demographics are particularly skewed as a legacy of the One Child Policy.

Maybe all this goes back to the reasons why humans are so fixated on pandas to begin with. A popular theory goes that human is that humans find panda bears cute because they resemble human babies, with their large cheeks, noses, and big heads.

During a brief stint as a kindergarten teacher several years ago, it made a deep impression on me how excited my kids—who were basically babies themselves—became whenever they saw a picture of a panda bear. We may love panda bears all the more because of their reputation for gentleness, with the view that pandas are vegetarians who primarily eat bamboo and seem to spend much of their time eating or sleeping. Or perhaps we envy what we perceive to be their lifestyles.

A form of anthropomorphization, then. But panda bears are wild animals. They might not exactly be apex predators, or even as dangerous to humans as their other bear cousins, but humans have been hurt and even killed by panda bears. There have been attacks on zookeepers, as well as numerous incidents of humans thinking that real panda bears are soft and cuddly, climbing into closed zoo enclosures, then unexpectedly being attacked. Sometimes the results are painful amputations, usually of hands or feet, but also sometimes arms and legs.

Before the modern view of pandas as cute arose, in ancient times, Chinese thought of as pandas as terrifying “monsters” capable of tearing apart metal gates. We think of pandas as cute only because when we encounter them, they are inside of cages.

What we see precisely in panda bears may be ourselves, in a distorted, furry reflection—an object of projection for our fantasies. This is the source of our love for and fascination for panda bears, as well as explaining why the panda bear became a vehicle for petty human politics.