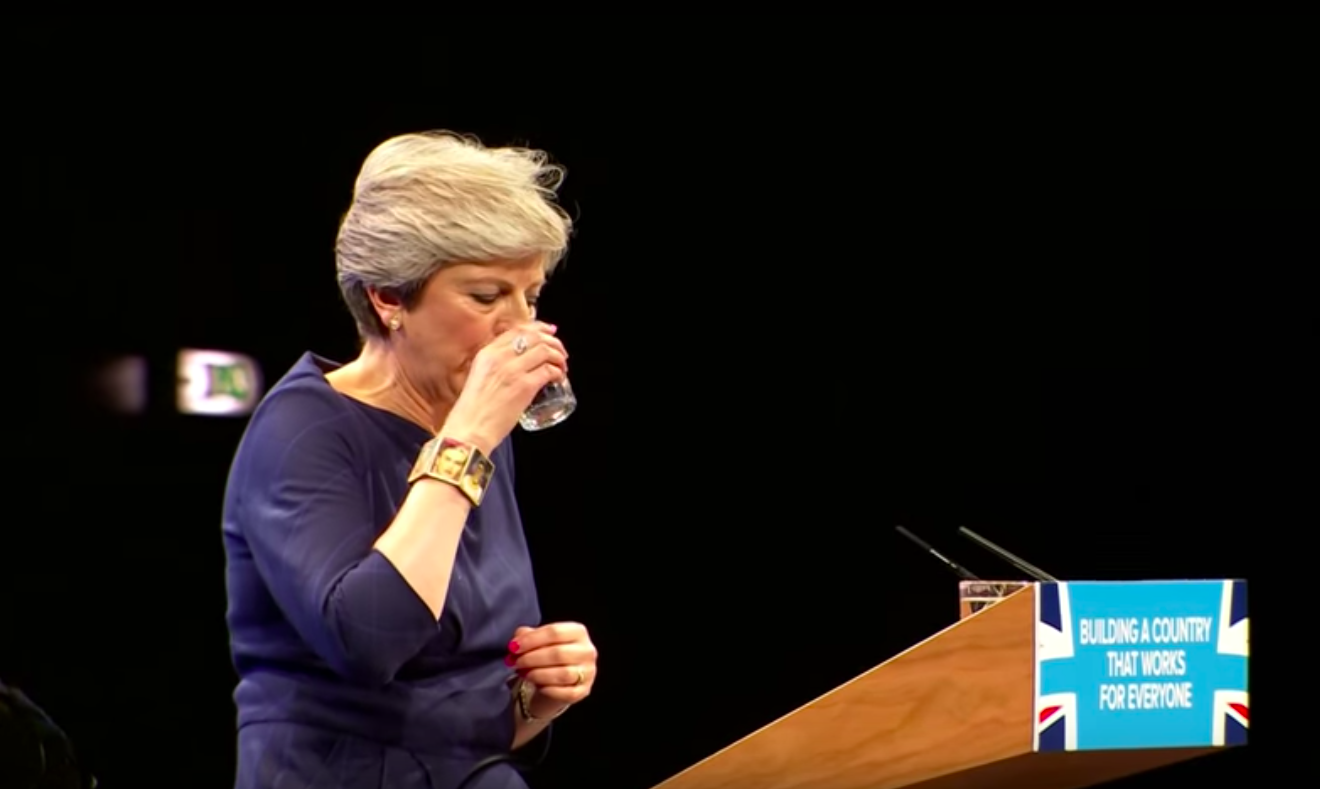

On the stage at the Conservative Party Conference in October 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May had a coughing fit. Probably no one would remember this, least of all me, had she not then paused to drink water, which meant that her sleeve slipped down her arm, revealing for a prolonged period of time a paneled bracelet composed of miniature portraits of Frida Kahlo’s face.

The British press had a minor field day at the time, trying to figure out what May was up to. Was it a total oversight that she decided to wear a bracelet depicting, as one journalist so deftly put it on Twitter, a communist “who LITERALLY DATED TROTSKY?” Was she trying to goad leftists somehow? Or was it some kind of coded message? “Was Theresa May’s Frida Kahlo bracelet a political statement?” a Guardian headline asked, hopefully—was May, for all her austerity politics, telegraphing that she was secretly a communist? Ever inane, under the banner of “Lifestyle/Women,” The Telegraph ran a listicle that posited “4 things Theresa May might have been trying to say with her Frida Kahlo bracelet,” including: “She won’t back down” and “She is a feminist.” This constitutes the #girlboss possibility; that like other conservative women, May was identifying not with Kahlo’s politics but with her gender, one “strong woman” to another. (There was also a half-hearted predictable “backlash” to the minor news cycle, which was basically a couple people online saying things like, “Why do we ALWAYS have to analyze powerful women’s outfits?” but that question is too boring to merit much discussion here). Additionally, people wanted to know, where could you get that bracelet?

Frida Kahlo is “having a moment,” The New York Times Style section proclaimed in 2015. She still is; it seems her moment knows no definite bounds. Having a moment means blockbuster exhibitions—last year, an exhibit of her personal artifacts and clothing at the Victoria & Albert Museum smashed attendance records. A version of the show opened in February at the Brooklyn Museum; meanwhile, an exhibition of her work is on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. But what would a moment be without merch? Frida’s moment has also meant refrigerator magnets and tote bags and dorm room posters and umbrellas and sneakers and nail polish tubes emblazoned with her face. Having a moment means she’s been transformed into a literal Barbie doll, a conspicuously skin-lightening Snapchat Filter, and not one, but multiple emoji.

Kahlo, a Mexican artist who died in 1954, used a unique style that blended folk art and fantasy with autobiography to explore identity, gender, class, pain, and the weirdness of the world. She is best-known for her self-portraits, or was, until she became a #Icon. The commodification of Kahlo even and especially by the museums who show her work, is widely noted with some discomfort and a kind of ennui. Shoulder-shrug-emoji. What can you do, after all? People like Kahlo, and they find something moving and relatable in her work, or perhaps in her biography, and brands—museums included—capitalize on this. Meanwhile, people come see her shows and she has achieved a global prominence unfathomable during her lifetime. Everyone ends up sort of happy, except for those of us who are cantankerous.

As for Kahlo, what would she have thought? People like to guess. Since she often played with identity and display in her work, and liked being photographed, some people think she might not have minded Fridamania. I tend to think that as an introvert and anti-capitalist, she would have disliked being a “global brand.” But this whole question—what would she have thought, anyway, about Theresa May wearing her face on a bracelet?—misses a crucial point about image-making. It doesn’t really matter, materially, what she would have thought. After her death, and even before it, she had almost no control over her images. Artists almost never do. They can talk about their work—the context and the content of it—and they can control, to a degree, its copyright, but now more than ever, images get swept away in the random tide of time and Twitter. They get repurposed and reinterpreted and misinterpreted; they can become a stand-in for something else entirely.

Which is sort of what happened to Theresa May at the Conservative Party Conference in October 2017: the images of her wearing her Frida Kahlo bracelet went “viral,” and people interpreted them however they wanted to—as a secret message, as a feminist move, as evidence of sexism against female politicians, as a kind of taunt to leftists. “Stuff means stuff!” claimed a glib Vanity Fair article about the bracelet, which argued, kind of, that the bracelet had to mean something even if we weren’t sure what.

With May is particular, this hermeneutics of minor details feels particularly essential because she doesn’t give the public a lot to work with, culturally speaking. Unlike, say, Obama, whose book choices, playlists, tan suits, college photographs, favorite sports teams, etc. were more than enough to allow us to sketch out a coherent “personality” for the president. With May, it’s more of a guessing game. That’s why I happen to be fascinated by the fact that she scrapes mold off her jam and eats it. That’s one reason why the video-turned-gif of her dancing (!) woodenly is so wonderful. An incongruity! A semblance of humanity! What are we to make of this?

May keeps wearing the Frida Kahlo bracelet. She wore it again the following year at the same conference. She wore it about two weeks ago, on March 14, the day when Parliament voted narrowly to postpone Brexit. “May always wears this bracelet on high pressure days,” a hardcore right-wing politician wrote accusingly on Twitter. “True colours.” Stuff means stuff, he was saying.

But what if…it doesn’t, really? The most likely explanation to me has always been that May likes the bracelet—that maybe she went to see the Frida Kahlo show at the Tate Modern in 2005 and visited the gift shop and picked up the bracelet. I think, too, that she continues to wear it because it’s a visual distraction, something that throws us off. It’s a literal shiny bauble for us to talk about, while we don’t talk about Brexit or austerity. It’s not a political statement so much as an anti-statement, a means of image-making that resists firm interpretation. She co-opts Kahlo’s images while repudiating anything resembling her politics, and the meaning of it all gets a little fuzzier, the closer we look, until it seems to mean nothing at all.