Taiwanese activists used to fear that any given visit to Hong Kong might be their last. That is, you might not be allowed in, the next time. Now it’s the case that if you visit Hong Kong, you might never be allowed to leave.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeStill, I went to Hong Kong to try and cover the Chinese National Day protests anyway, which commemorate the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Going there was irresponsible, it was reckless, and I know it. I was at some risk of being detained and shipped to China on trumped-up charges.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeTalk was that the People’s Liberation Army might use force in order to prevent the international spectacle of protests in Hong Kong with simultaneous celebrations in Beijing. This possibility looked increasingly unlikely as September dragged on, but the nagging sense endured that protests could potentially escalate to a new level of police violence.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeWhen I was in Hong Kong last June, during the start of the eighteen weeks of protest which have since raged on through the summer, I had just decided to drop everything and go, begging my friends to pick up the slack on New Bloom, the publication we had founded together after the Sunflower Movement in Taiwan.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeIt was a risk. But I guess that I would have felt like a hypocrite otherwise. My politics regarding leftism, Taiwanese independence, and all these other things would all seem rather meaningless to me if I’m not willing to put everything on the line for them. I would have just felt like a coward. Maybe I felt I had something to prove to myself. I would have never really been able to live with myself if I didn’t go; I would have always regretted it. So it was easy to make the decision.

There are at least three Taiwanese currently kidnapped by the Chinese government. Two of them, like me, are activists. One disappeared after entering Hong Kong and participating in the demonstrations there, though all three of them disappeared after entering China. All three are imprisoned on charges of “endangering state security.”

Well, I was not stupid enough to try and enter China. But it could be made to appear as though I had decided to enter China of my own free will. I’m not famous enough that it would protect me from being kidnapped, but I’m well-known enough that kidnapping me might scare the right people.

That fact that I’m also an American wouldn’t protect me either; it might even make me a target, as a pawn in the US-China trade war, or as a retaliatory move against the passing of the HKRDA. China might even come after me as a good way to pressure both the US and Taiwan at once. These days, whenever I have a flight that gets diverted, I’m terrified that it’ll be diverted through China.

But quite a few fellow Taiwanese activists have flown over to Hong Kong in recent weeks. Some have posted pictures of themselves fighting with police as “frontliners” in the protests. I thought it extremely reckless when I saw activists far more well known than I am, who have done this—yet I decided to do it, too.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeThe week before I went over, I tried to meet up with as many friends as possible. With the looming possibility of serving up to five years in a Chinese jail on trumped-up charges of endangering state security—the fate of Lee Ming-Che, the first Taiwanese activist that was kidnapped by China—it could be the last time I saw them.

Maybe I was overreacting. I joked to a close friend, a Hongkonger living in Taiwan, that I was behaving as though I were dying. I wouldn’t have tried to go if I didn’t think that it was highly unlikely for me to get kidnapped by China. But I also really didn’t want to spend five years in prison for no reason at all. I would be 33 when I got out of prison, if it were five years. There would go some of the best years of my life. Lee Ming-che’s father recently died, and Lee was not allowed to attend the funeral. God only knows what big events in my life I would miss if I were trapped in a Chinese jail for the next five years.

There are already Hongkongers the same age me facing up to ten years in jail. Some of them are already serving their sentences.

Some Hong Kong activists have already fled to Taiwan, since Taiwan has no extradition with Hong Kong due to its unusual legal status (a key factor, actually, in the murder case which sparked the current political crisis in Hong Kong). According to a report by the Apple Daily in July, there may be more than 60 such activists currently in Taiwan.

I learned before I went over that the Hong Kong police were searching travelers coming from Taiwan in the lead-up to Chinese National Day—particularly young Asian men in their 20s and 30s. With dwindling supplies of gas masks, safety helmets, and other protest gear in Hong Kong, Taiwan had been sending a lot of supplies over to aid demonstrators. Enormous solidarity rallies for Hong Kong have taken place in Taiwan. I covered one right before I flew over, with 100,000 participants, just one of six solidarity rallies that took place across Taiwan that day. There was a week in June with solidarity rallies for Hong Kong every single day in Taipei, each one organized by a different group.

So it’s not surprising that many Taiwanese would fly over for National Day. I imagined that a lot of them would be like me, having a history of protest in the Sunflower Movement or other Taiwanese social movements. I’ve wondered at times where all these faces I vaguely got to recognize from the Sunflower Movement had gone over the last five years. It was strange to think that we might meet again thousands of kilometers away, on a different battlefield but still fighting the same fight, basically.

As compelled as I was, from another perspective it all seemed a bit pointless. I would just be parachuting over from elsewhere to cover the protests, like so many “international” journalists do whenever something big happens in Hong Kong or Taiwan—showing up quite clueless and needing to rely on more informed locals. I knew my reasons for wanting to be there were primarily emotional, not logical.

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

Brian HioeBefore the day of my flight, I arranged with the other members of my publication, as well as the Hong Kong publication I joined recently, to put out an alert if I didn’t respond within a certain period of time.

I even set up a contingency plan of what to do if I was kidnapped. Like how some of the protesters in Hong Kong have taken to writing wills before heading out to a protest in case they die, I even wrote a sort of will in case I ended up in a Chinese prison for several years incommunicado. Who is to say that every prisoner lives through the entirety of their jail sentence, given what prison conditions are in many parts of the world?

The day of my flight, a typhoon that almost nobody seemed to have anticipated struck Taiwan. My first flight was canceled and I struggled to make a second before later discovering that it, too, had been canceled. I decided to bite the bullet and buy a new ticket with a different carrier, and then unexpectedly discovered that my second flight was still on when I got to the airport. Had I made a mistake? I hurriedly canceled the new flight I had bought. I’m still not sure whether I’ll be getting any refund back. My wallet, it cries tears of blood.

It felt like fate was trying to prevent me from going to Hong Kong by sending a typhoon at me. “I’m being deprived of my chance to be thrown in a Chinese jail for the next half-decade,” I complained to my Taiwan-based Hongkonger friend. A colleague joked that Mazu, the sea goddess, was trying to save me.

But nothing happened when I arrived. I got in without incident, clearing immigration significantly faster than any of the other times I’ve been to Hong Kong. On the plane over, I’d scanned the cabin for others my age who didn’t seem to be Cantonese speakers—who would likely be Taiwanese. I didn’t see any. The airport itself seemed strangely empty.

I posted a picture of myself on my publication’s social media presence once I arrived. I figured it was better if I publicized my being in Hong Kong. It’s harder to disappear when people are watching, after all.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeAs I walked among the people in Hong Kong’s streets that night, I kept wondering who among them might be a protestor—wearing black, identities concealed, and fighting with the police on the weekends. There’s a sort of anonymous kinship between Hongkongers who might not know one another’s true identities during the daytime, separate from the “parallel universe” of street clashes with the police.

I spent the day with friends on Hong Kong Island. We were in front of Government Headquarters when they started firing tear gas and deployed their water cannon truck. We were ducking around city blocks, trying to escape notice from police in Wan Chai when they began to fire tear gas everywhere. Most of the action there took place just a few blocks from our hotel.

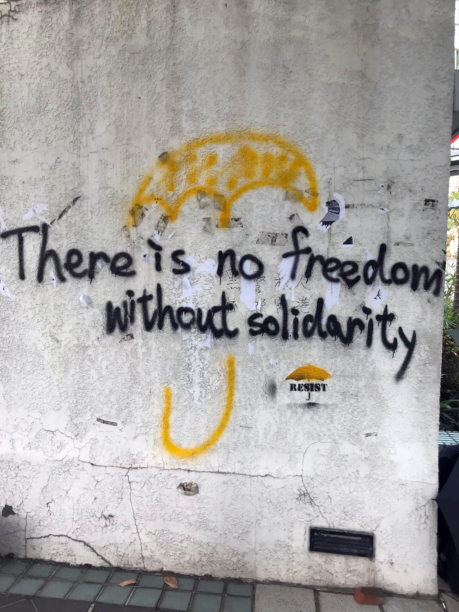

It was uncanny to see the city streets so transformed. Bricks uprooted from the ground were made into barriers against the police. Graffiti and posters everywhere on what would otherwise have just been drab urban landscape. Ghost money scattered everywhere, symbolically mourning for what many saw as a dying city. Protesters chanting, “Restore Hong Kong! Revolution of our times!” or “Five demands! Not one less!” in Cantonese, this sometimes beginning with a single person with no warning and echoed by a large crowd. Demonstrators singing “Glory to Hong Kong” and other protest anthems.

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

Brian HioeAs with the last time I was in Hong Kong, I was struck by how young many of the protesters seemed.

I’ve been on the streets protesting in some form since I was seventeen, so I’ve been there. And I have to say, social movements are not a very mentally healthy thing for a young person to go through—it destroys some people rather permanently. I still carry my own scars from all the past movements I’ve participated in.

Another striking feature: the number of protester couples there were. They would both be wearing black—black balaclavas, gas masks, helmets, and goggles. They would be holding hands as they walked during the marches. During the clashes, they would be watching out for each other in the thick of it. I hadn’t seen that in June.

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe“Man was born for love and revolution,” I like to tell myself, an Osamu Dazai quote. I think of it as my motto. It’s what I try to live for. Love and revolution. But it’s actually quite heartbreaking to see that in real life.

Since I was posting live updates the entire time, my eyes were glued on my cell phone screen as I was trying to compose Tweets and Facebook updates, even as tear gas went off around me.

There are a lot of expat bars in Wan Chai, and consequently there were a few odd white people drifting around the action the entire time, without masks. One of these expats said, passing by, “What are they going to do? Shoot me with a rubber bullet?”

One of us commented, “That might be the purest form of white privilege I ever heard.”

We also got a kick out of watching another pack of expats that drifted around the action looking for beer, since all the convenience stores were shut down. One of their group was also named Brian, we overheard from their conversation. During a point at which police seemed to be firing tear gas at a mostly empty section of Hennessy Road, I spotted him across the street with a beer can in hand.

“Brian finally found beer!” I exclaimed, and we all cheered.

Another friend ducked into a restaurant that took in any nearby protesters before closing the shutter, which unfortunately got jammed. They even handed out plates and utensils to all the demonstrators caught inside, so they could pretend to be customers, while the frontliners in full gear hid in a back alley. I have some recollection of walking by a restaurant that may have been this one and thinking, “People are still eating during a time like this?” So it may have worked.

Life goes on, I guess. You could see quite a lot of people trying to go on with their regular day as the protests went on around them.

As for me, nothing happened to me that day, aside from a close call when a tear gas canister exploded into flames five feet from me. I got away fine.

But on that same day, the police shot a kid, the first time a demonstrator was shot with a live round during all the months of demonstrations that have raged on since June. The bullet was reportedly 3 centimeters from his heart and he’s on artificial respiration, though his condition later stabilized. He is eighteen years old. The police later claimed this was justified. Shooting children. Despite his condition, police are still charging him with charges of “rioting,” which could mean a ten year jail sentence.

Far from being a celebration of the 70th anniversary of the glorious founding of the People’s Republic of China, it was just another day for Hong Kong, in a time in which the everyday has become dominated by tear gas and riot police. I really don’t know what will happen next.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeI flew back to Taipei the next night, again feeling tense that I could potentially be detained on the way out. Again, nothing. I thought I was in the clear once I passed through immigration, seeing as it was unlikely they would drag me off a plane, but I felt vaguely nervous until the moment the plane took off.

Once I arrived, I had to find somewhere to sit down in the airport and just text everyone I was home and safe. Well, it was a relief. But that’s the new normal. It won’t be so easy for me to go to Hong Kong anymore, knowing that any trip there could be one I don’t come back from.

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe