Look around you. You’ll see that ambient white light which is the sound of each soul whispering to the souls around it. That’s where we begin. These voices you hear around you are the sound of pain and strength and hope: hope for a new beginning, for a sweeping away of the darkness and the injustice of the years of embers, for an unfurling of stars in the sky once again, for a sowing of seeds from which love will grow, for a new sunrise that will shine light into every dark corner so every soul will yield, and every heart become calm.

Here I was, then. With the red chairs, and the walls covered in clean engraved mirrors. On the other side, the wall was white and two paintings had been hung on it. One of them caught my eye: a woman wearing the traditional garment called a safsari.

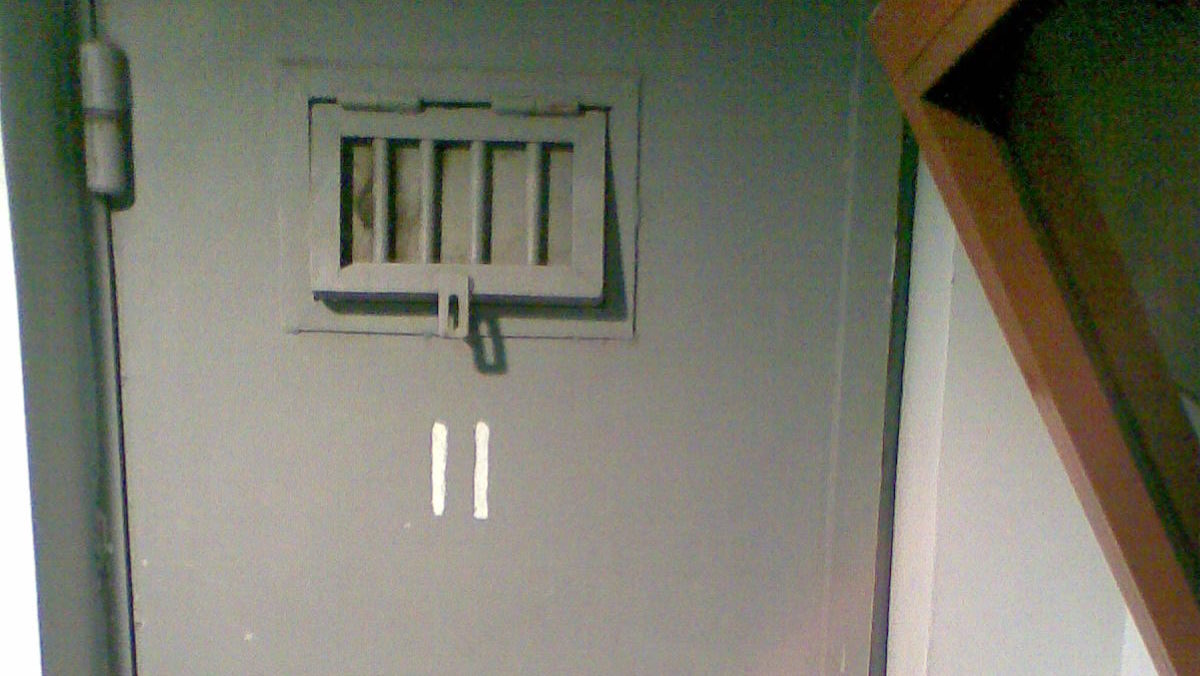

The picture reminded me of the women who fought. They were a refuge, a source of support, prophets even, in the lessons they taught us about how to be patient and steadfast and loving. They were our only link to the outside world when we were in prison.

When we fight for what we dream of, what we believe in, what we want, it’s that we that matters. The we that accompanies our actions and words, our thoughts and principles, everything we’ve done, past and present. The we contains the I, and cannot be achieved unless all the many Is band together into a single we.

When my mother used to visit me in prison, I used to eagerly snatch her handkerchief before I took the quffa—the basket of food and supplies she’d brought—or even said anything to her. Mom was so tolerant of my strange ideas and requests! I used to make her tuck a handkerchief inside her clothes and not take it out until the next visit. That handkerchief kept me company, kept my spirits up, kept my homesickness in check. Through it I could smell everything that had happened at home while I was away. The scent of the henna that covered her palms never left me—even though I’d always hated it when I was young. The smell made the nine months of prison easier, wrapped me in the womb of its protection. Even after I left prison I was adamant that my mom keep her hands dyed with henna so I’d always be safe.

From the white leaves of paper where I released my sadness by writing, and defending the rights of the oppressed, to the green leaves of henna furled in the center of my heart—how is it that leaves can represent a country for someone?

My thoughts were interrupted by a female voice enquiring, “Excuse me, Madame Baya?”

“That’s me,” I replied. “I guess you must be the journalist that called me last week?”

The younger woman nodded, smiling and trying to keep a handle on her emotions. She’d been waiting a long time for this meeting, to talk to Madame Baya and to look at her; to memorise what details she could of her features, the sound of her voice. But she had to be professional in this interview: she wanted to earn Madame Baya’s trust, to befriend her, and maybe be lucky enough to get another meeting. She’d turned up two hours before their appointment just to watch, from a distance, this woman, so renowned for her wisdom even though she was so young. What was the secret of her strength and pride, and the smile that never left her face, despite that piercing gaze?

She’d known about Madame Baya since she was young. Whenever her name was mentioned, it would be in a hushed voice, she’d noticed, accompanied by a careful glance around to check that nobody had heard. That’s what had first made her curious, that’s why she was so excited to meet her now. She’d spent nights trying to visualise her, trying to picture her face. Would she have pale honey-colored eyes and long black hair? Or would she look like the women in the neighborhood, pale and heavy? She’d once seen a picture of Madame Baya in a foreign magazine, though, wearing her lawyer’s uniform and raising her right fist as she marched with other lawyers against the regime. In real life, her features were both strong and gentle at the same time, and she was slim, and not as tall as it seemed in the picture. Most eye-catching was the set of her face, which was plump, with a dimple in her left cheek and large eyes filled with a dreamy gaze. In the photo she had been shouting so hard the veins on her neck stood out. The protest attracted a lot of international attention at the time, especially what with the persecution the protestors had faced in the aftermath. She spent nights talking to the photo.

And so she grew up dreaming of meeting Madame Baya and getting to know her. She used to peek through the keyhole when Uncle Azhar visited them in his long brown coat and black hat. Uncle Azhar worked secretly with her father in the party of which Madame Baya, too, was a member, and he might say something about her. Then her mom found her spying and told her off. The telling-off didn’t stop her thinking about the brave and noble lawyer. And now here she was.

How can a single year bring so many events and people and experiences? Especially those moments that snatch you out of the light, where you were so happy, and shut you in a cellar of darkness where there’s nothing for company but your own fear and weakness and everything you’ve run away from, and you know, then, that you’re weak and you have no-one to turn to and nowhere to go. At these times all I have is my imagination and the recollections that are strewn around the corners of my memory.

I remember then the sound of her voice; it comes back in the darkness. That tone brings her back to life every time, the hoarseness that sends my blood racing through her veins when I hear it, even in memory. That embrace that shelters me and sings to me of every nation in the world as if they’d been created for me alone. The limitless ability to love and give and sacrifice, that makes me embarrassed to admit to the weakness or fear in front of me, because what I’ve been through can’t possibly compare with what happened to her, not even in the simplest details.

It was she who held my hand and led me out of the darkness and into the light, where I gathered up what was left of myself and used my soul’s resources to sculpt it into shape. She, whom despair and fear could not touch; our coming together that year was one of the most momentous things that ever happened to me. Her door had been closed all those years, but she opened it to me, and through her experience I learned, through everything she witnessed in all the places life took her.

We cannot be reduced to a single time or place, but only to the burdens we carry in our wounds, and what wanders in our thoughts, and what our souls dictate to us. That is how we shape and outline. That is how we watch, with the eyes of our hearts. Borders collapse; differences in age and experience and appearance no longer mean a thing. That is how our bonds are dissolved.

This original Arabic short story & English translation come from an anthology of writings by Tunisian women, all of them former political prisoners or witnesses of state repression in some other way, edited by Haifa Zangana (already published in Arabic, forthcoming in 2020 in English) produced by the Voices of Memory project with the support of the International Center for Transitional Justice and the University of Birmingham.

Houneida Jrad is a civil society activist and psychology student. “I wasn’t directly affected by the dictatorship but I used to see things that happened, threats, which I couldn’t find a satisfactory explanation for at the time. It became clear to me that there was a certain way of dressing and certain kinds of activities that weren’t allowed, though I didn’t understand why. Until the revolution—then I understood everything that was previously hidden from sight.”

Katharine Halls is an Arabic-to-English translator. Her translation, with Adam Talib, of Raja Alem’s novel The Dove’s Necklace, received the 2017 Sheikh Hamad Award for Translation and International Understanding and was shortlisted for the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize. Her stage translations have been performed at the Royal Court, the Edinburgh Festival, and across Europe and the Middle East.