At the September primary debates, Democratic presidential contender Andrew Yang related a folksy bit of family lore. ‘My father grew up on a peanut farm in Asia with no floor’, he declared, ‘and now his son is running for president’. Yang’s extremely vague geography drew laughter in some corners of the Asian-American community. The Korean-American writer Jay Caspian Kang joked in a since-deleted Tweet, “‘Yang’s dad grew up in one of those restaurants that serve pad Thai, sushi, bibimbap and boba. Love it.”

Perhaps the reason Yang was not more specific is that his parents hail from the geopolitical flashpoint of Taiwan, a democratic, de facto independent state of 24 million people.

In many circles, inside the US and out of it, Taiwan’s separate existence from the PRC is treated as radioactive for reasons old and new. Home to indigenous peoples for millennia, Taiwan was successively colonized beginning in the 1600s by the Spanish, Dutch, Ming rebels, Qing, and Japanese. In 1949, the Kuomintang, the defeated party in the Chinese Civil War, made Taiwan the home base of the Republic of China in the deluded hope that they would one day be able to defeat the PRC. Who represents the ‘real’ China has thus been framed as a competition since the 1970s, resulting in the systematic exclusion of Taiwanese from international organizations ranging from Interpol to the World Health Organization—even as Taiwan matured into a thriving democracy after nearly four decades of KMT dictatorship, moving away from authoritarianism and allowing its people to speak and travel as they wish. As the PRC has risen in might, it has consistently tried to erase the island nation’s unique political and cultural identity, making it clear that any attempt to shed the ROC framework, or otherwise formalize its independence under the name of Taiwan, might be met with invasion.

This makes the silence around Andrew Yang’s Taiwanese-American heritage that much more striking. In December 2016, then president-elect Donald Trump was lambasted for taking a phone call from Tsai Ing-wen, the moderate, wonkish president of the ROC, by liberal American commentators demonstrating little knowledge of the relevant geopolitics. In September 2018, Peter Beinart penned an article in the Atlantic proposing that the US secure peace in East Asia by allowing the PRC to take over Taiwan, an argument that has aged poorly in the wake of the Hong Kong protests and the continuing revelations of the internment camps in Xinjiang. As part of a coordinated campaign of intimidation, the PRC recently pressured dozens of multinational corporations to describe Taiwan as ‘Taiwan, China’ or ‘Taiwan, Province of China’ on their websites.

Given the obvious tensions, it’s worth asking why there’s been so little discussion about what it might mean for international relations to nominate a Taiwanese-American as the Democratic presidential candidate.

Requests for clarification of Yang’s Taiwan policy for this article went unanswered by his press office. Perhaps his lengthiest public comments on Taiwan so far came in October, when he told CBS reporter Nicole Sganga that ‘the Taiwan issue has been with us for decades’ and that a ‘positive continuation of the status quo should be one of our top priorities’, including ‘a relationship that works for both Taiwan and China’. Yang stated incorrectly that the US has a ‘mutual defense treaty with Taiwan’. (The Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty was abrogated in 1979, the year that the US established formal diplomatic relations with the PRC. In its place, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act, which governs arms sales to Taiwan and allows for the maintenance of an unofficial embassy on the island, the American Institute of Taiwan.) Yang also failed to clarify that under the ‘status quo’ Taiwan is already independent from the PRC.

A significant element of the reason for the US media’s silence on Yang’s Taiwanese-American heritage is attributable to the very Asian-American writers, academics, and activists who have kept him in the news. By analyzing Yang primarily in terms of how much he leans in to classic ‘model minority’ stereotypes, they have flattened and homogenized his background while sidestepping the most pressing questions on foreign policy and identity formation raised by his candidacy. For example, in response to Yang’s awkward October debate quip that he knew ‘a lot of doctors’ because he was Asian, Frank Shyong remarked in the Los Angeles Times on the irony of a ‘powerful man on a powerful stage, powerless to be himself’, without elaborating on why a Taiwanese-American, in particular, might feel this way.

The sociologist Nancy Wang Yuen recently described Andrew Yang on Twitter as the ‘first Chinese American presidential candidate’ and responded to evidence of his (sometime) identification as a Taiwanese-American by arguing that the ‘difference between [Chinese and Taiwanese] is much more nuanced’ than her critics seemed to think and that ‘there are Taiwan-born [and] -raised folks who identify as Chinese, not Taiwanese’. Her statements, however, overlook trends in present-day Taiwan, where 73% of people ages 20 to 29 identify as Taiwanese only. Polls now consistently show that fewer than 5% of people living in Taiwan identify as Chinese only.

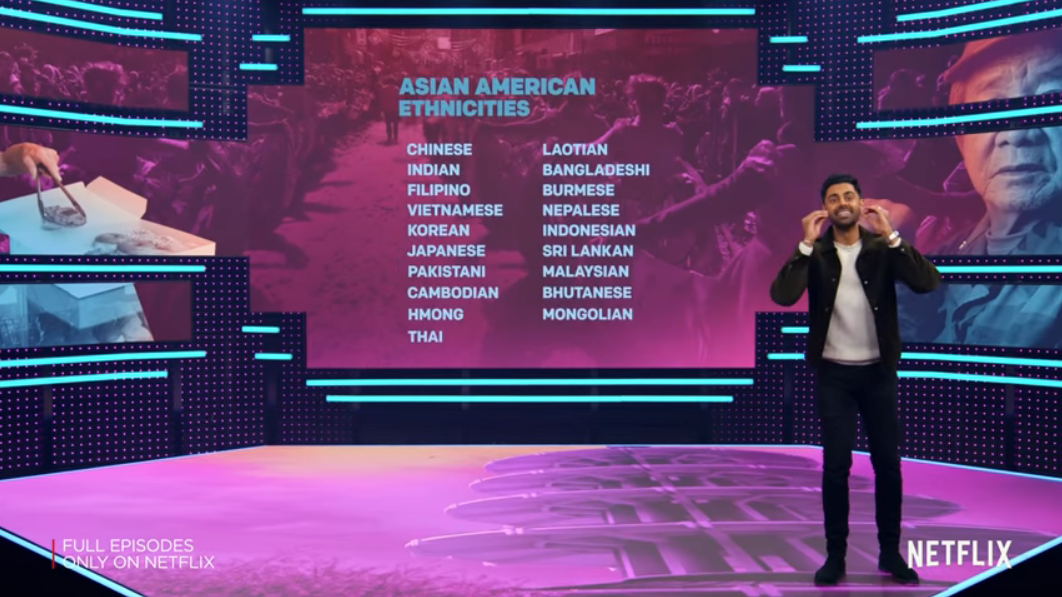

In ignoring the possible reasons why Yang code-switches between identifying himself as Taiwanese- and Chinese-American, many observers and analysts have neglected the persistent pressure on Taiwanese-Americans to soften our identities and avoid confrontation, both in Asian-American spaces and majority white-American ones. In some cases, our fellow Asian-Americans erase us from the conversation altogether. In a December episode of his show ‘Patriot Act’ on turning out the Asian-American vote, the comedian Hasan Minhaj poked fun at the way MSNBC failed to include Andrew Yang on relevant infographics and then promptly left ‘Taiwanese’ off his own list of ‘Asian-American ethnicities’ [clip above at about 10:20].

These dynamics help to explain why the most prominent members of the Taiwanese-American diaspora, such as Jeremy Lin and Constance Wu, aren’t vocal advocates for the country’s continued freedom. By the time a person with immigrant parents from Taiwan achieves fame, he or she is also liable to have formed alliances that might be endangered by openly championing Taiwanese independence and decolonization.

Thus the phenomenon that is Andrew Yang: a Taiwanese-American candidate who has so far not said much about Taiwan. A candidate whose parents returned to Taiwan but who, like his fellow Democratic contenders, has no discernible platform addressing the 1300 missiles the PRC has pointed towards the island. A candidate for a political party that, at the executive level, has long shirked the responsibility of forward-thinking policy about Taiwan, ensuring that the island nation continues to be treated by stalwart Republican champions in largely Cold War terms, as an anti-Communist, open-market alternative to China.

As a cohort, the Democratic candidates for the 2020 elections have been lauded for their racial, gender, and religious diversity. The promise of someone other than a straight white male as a potential president is that new voices and ideas, born out of lived experience, might emerge from the Oval Office. But this outward appearance of diversity will serve no purpose if a Taiwanese-American candidate’s campaign will not do more than others to make Taiwan comprehensible in politics and policy. What Yang represents to fellow Taiwanese-Americans is thus the limits of representation, and how little the situation of Taiwan and its people might change on the remote chance that one of them is elevated to the highest office in the United States.