Clutched to my chest, slipped inside a blue plastic folder, were the papers that mattered most to me. They documented the broad strokes of my life—where I was born, where I live now, who I am married to—and I was sprinting across a parking lot with all of them as monsoon rain swamped everything around me. I had not thought to bring an umbrella, and the Foreigners Regional Registration Office where I needed to submit these papers was just past the bus terminal up ahead.

India’s equivalent of a green card would allow me to officially work in Bengaluru, where I live with my wife and small cat. I thought about how funny it would be if my shoe clipped a curb and my passport and birth certificate swirled into the air and landed splat in some huge puddle, the kind of funny that’s only funny in six months, when everything’s been resolved and none of it matters anymore. This was my third trip to the same office to apply for the same thing, and accidentally spilling my paperwork all over the rain-washed asphalt would just be another seemingly random obstacle in my quest.

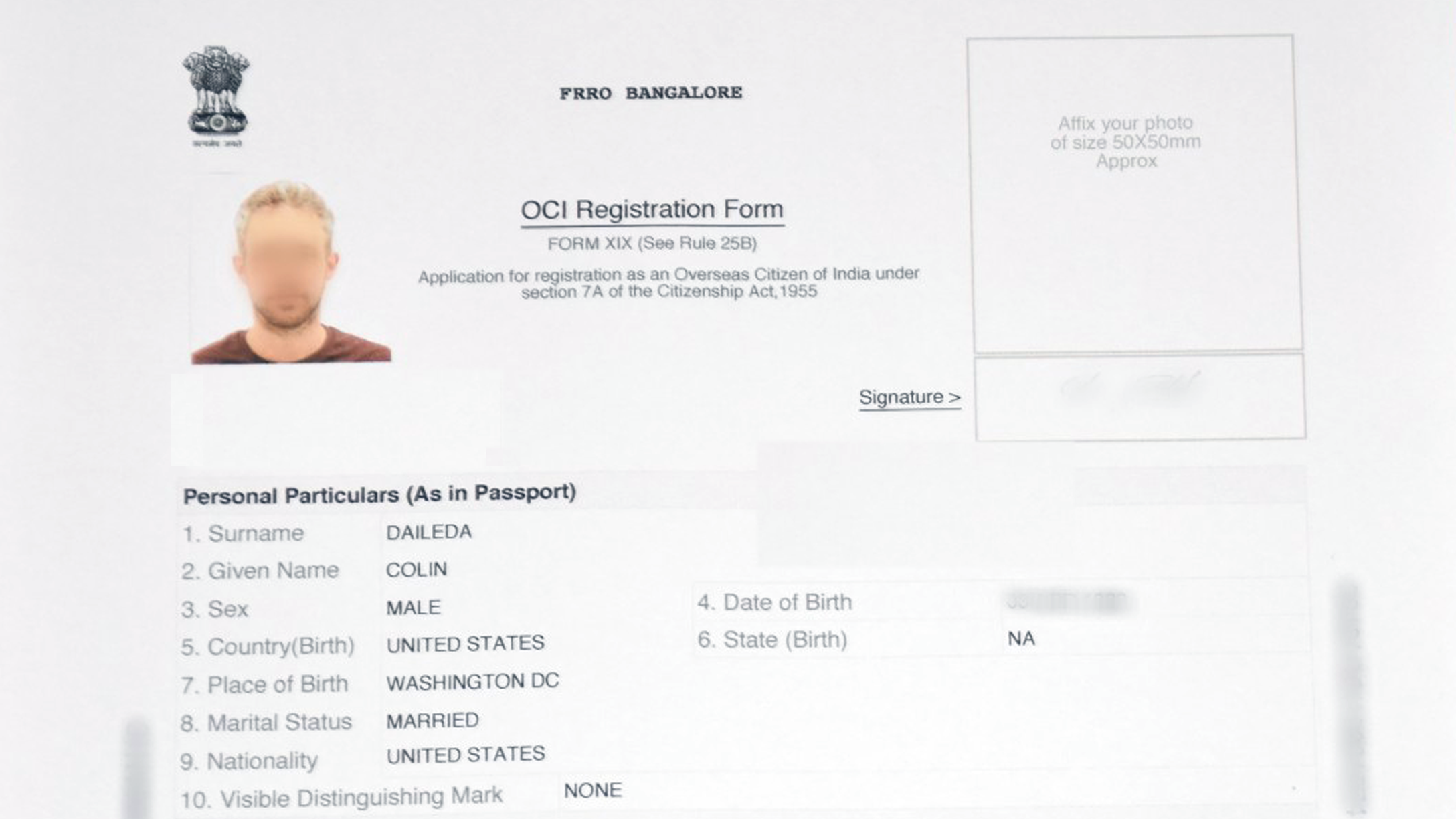

The Ministry of Home Affairs requests different sets of information depending on the page of rules you’re reading. Applicants for this Indian green card (it’s called an Overseas Citizen of India Card, or an OCI) have to submit copies of all these documents online before going to the office, but the submission page has more slots than required forms, and so I started the application over because I thought I’d misread something, which I had not. Then there were the photos, which were supposed to be the same size as a passport photo, but also, perhaps, a bit bigger.

On my first visit to the office I’d stood in the elevator with the operator, who sat in a chair looking understandably very bored, until the doors opened onto a wide room with chairs laid out before officials behind a long desk, just like any DMV. Very few people were there, and so I handed over my documents and was immediately told I had to bring more copies and could not submit this today. On the second trip, I was told my marriage certificate was not official enough, that this one stamp was not the correct stamp, and after some arguing I wound up back in New York, waiting my turn in another office, to get another copy of my marriage license. It was stamped in the same way, and it was fine on the third attempt. I don’t know.

Just before taking a seat, people with business at the office have to sign a booklet and list their nationality. My third visit was the busiest, and I glanced down the list of countries before signing in—a few people from Nigeria, a few from Oman, two from Pakistan, two from Yemen, and then much farther down was me, the only one from the United States.

I signed my name and looked for a seat. The people from Yemen and Pakistan had signed in something like an hour before, and so maybe they were already gone, out again somewhere in the city.

Two weeks before I got my OCI, The New York Times published an article that featured a photo of Amal Hussain, a Yemeni girl who was 7 at the time, just before she died. Her skin is withered, bunched at her elbows and pulled over her ribs, which look as though they’re about to rip up through her chest. She died of starvation, which is the intended effect of a strategy of blockades and other forms of economic terrorism employed by a Saudi Arabia-led coalition against northern Yemen. As the Times put it, the effect has been to put the country on the verge of a “famine of catastrophic proportions.”

A little more than three months after I got my OCI, the Indian air force blasted a patch of forest somewhere near the little town of Balakot, in Pakistan. Military aircraft from either country hadn’t crossed the “line of control” since the war in 1971, the “line of control” being the term used to define where India-controlled Kashmir meets Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, because no one can agree on an official boundary. Pakistan shot down an Indian fighter jet the next day, capturing its pilot, who was released two days later.

During those 48-ish hours, the possibility of war was all anyone talked about. All televisions were turned to the news; greetings were abandoned when walking into the homes of friends and family. Newcomers silently joined the group already staring at headlines, until someone broke the quiet by mentioning a rumor they’d heard, and then everyone was off on their own theories about what had happened and what was to come. Maybe Pakistan had really captured two pilots, and so where was the second one? Maybe the Indian air force, as the government wanted its nation to believe, had actually blasted a “very large number” of militants, and not just a thicket of trees. The sky north of Delhi was briefly declared a no-fly-zone, and my wife and I wondered whether her brother would be able to board his flight home in a couple days. The Indian air force’s planes were outdated and ill-equipped to handle Pakistani fighter jets, one heard. Others said that the nuclear weapons both countries possessed would turn even far-south Bengaluru into borderland.

I wondered how all this would have seemed for the two people from Yemen and the two from Pakistan, and if they too had been confused about what to submit on the Ministry of Home Affairs site. How would it have felt if they’d showed up at the office only to be told that they had to bring more copies of their passport, their visa, whatever. How to tell, in the moment, whether something will be quickly fixed or is the start of a life-altering blockage? The quaint inefficiencies of a bureaucracy are only trivial if their consequences don’t much matter or will surely be ironed out soon.

What if the official who hadn’t liked my marriage certificate stamp said the same to any of them? If an Indian official tells you to go back to your native country to get a new stamp, and your native country is Pakistan, what are the chances you ever see India again? Especially if you go back and, suddenly, the world is talking about nuclear war? What if you are told to go back to your native country for a stamp, and your native country is northern Yemen? What is it like to argue with an official over the veracity of a stamp, when his refusal to recognize it could send you to starvation?

For me, all these encounters with bureaucracy only amounted to sitting in more traffic, buying an ink cartridge for my printer, running through a downpour, and a trip back to New York City that had already mostly been planned. Just a funny story I told friends a few months later. But it’s not hard to imagine, say, the U.S. making an arms deal with Pakistan, and India officially or unofficially deciding it doesn’t want Americans wandering about its country with work permits and a license to stay as long as they like. The questioning of a stamp morphs from one man arbitrarily wielding a bit of power into the tacit support of a system that has suddenly realigned against the plans my wife and I have made for our lives. I could spend thousands of dollars on flights home for new documents or whatever only to walk up to the counter at the registration office and be told “no,” because saying “no” is easy.

The historically massive upheaval we are living through—in India and Iraq, in Iran and Pakistan, in Hong Kong and Bolivia, in Brazil and China, in Ecuador and Yemen, in Syria and Palestine—make it obvious that no one rests outside the power of government to upend our lives. That power can be concentrated into a small stamp on a piece of paper, but it can also corrode the meaning of the documents that undergird a sense of self, in the absence of any ink at all.

Until a few years ago, I was one of those U.S. citizens who had never considered the value of a passport that is a near-universal key to the world; was confused about having to ask India for permission to visit when I first applied for a visa. Entering another country, I would hand my passport to a stern-faced security person, he would stamp it, and it was easy to imagine that I was granted this access because all these nations respected at least the American facade of freedom. Now it’s impossible to convince myself of even that lie. A country both hugely rich and unconscionably violent, that rips children from parents at its southern border and watches while they die in cages makes clear that when its citizens lay down passports in front of immigration officials in other countries, this is not a request.

It doesn’t seem like a great leap from where we are now to a point at which the U.S.’s militant fondness for borders becomes an impetus for other countries to wall Americans off from their worlds. Every time I hand my passport over to an officer in Bengaluru, it feels a bit like a demand made from behind the barrel of a gun, my passport less a key than a hammer.