You’d never guess from reading last week’s issue of How To Spend It that human civilization is teetering on the brink of collapse. By chance it was published March 27th, the very day it was announced that UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson had tested positive for COVID-19. He was admitted to the ICU at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London a few days later.

[Update 4/12/20: Johnson has been sprung from the hospital and is recovering at Chequers.]

How To Spend It, the glossy weekend supplement of a great newspaper, the Financial Times, is stuffed with ads and reviews of luxury goods—jewelry, watches, “high-end” travel. Massive diamond rings from Harry Winston give way to an overwrought Blancpain watch the size of your head (“Villeret Carrousel Moonphase,” $120,800), followed by a dead-eyed model in an unfortunate sequinned getup from Louis Vuitton.

What on earth does any of this mean, can it mean, right now? What is the cultural significance of a $120,800 watch as millions of unemployed, uninsured Americans struggle to get $600/week relief from the government? What perverse conception of “taste” is implied by it? This thing is like the magazine version of The Garden of the Finzi-Continis on acid.

“The coronavirus has thrown so many things in the air,” writes newly appointed How To Spend It editor Jo Ellison, lamenting the “major watch fairs cancelled”—and not only that!—“a dozen events designed to capture the immersive quality of the new luxury experience are in the balance.” Bummer! But what about barns, Jo? “Barns inspire in me a kind of pioneer-style excitement.”

“The Aesthete” column features motor-racing champion and super non-aesthete Jamie Chadwick (“I feel like I’ve got a lot of stamps on my passport”); there’s a piece about whisky stones, and another in which “ankle boots take you from desk to dinner.” Dude you cannot GO to dinner now unless you mean like the distance between your office and your dining room. To be fair, all this was written before the UK’s feckless prime minister landed himself in the hospital, but any halfway sane observer of the burgeoning catastrophe could have told you exactly where Johnson’s breezy schoolboy nonchalance was headed. (And did.) The luxury machine rolled on, anyhow.

Here’s an “off-the-radar Costa Rican eco-lodge” that costs nearly a thousand USD a night, for people who want to holiday “somewhere elegant and soulful.” Its owner “is openly questioning how much we really need, and why.”

I’ve been mocking this worthless rag forever, but even in mid-mockery I admit, I was also admiring the sumptuous photographs of the beaches at Phuket and the markets in Penang.

How To Spend It reminds the rich that they wouldn’t have a clue as to How unless they were told, as the Guardian’s Andy Beckett observed: “With striking bluntness, the magazine’s name says as much.” But it also flatters the would-be cognoscenti who once visited all those museums and theaters and restaurants we can no longer get anywhere near, people who loved beautiful things and wanted to see the world, in photographs at least. Those with not much to Spend, but who fancied they knew How, were on the same demented ride.

My first grownup jobs were all working for rich people in Los Angeles, in between going to school. I was a private secretary for a screenwriter and her director husband, in their cozy old Spanish house tucked up in the hills near the Hollywood Bowl, and later I worked for a “celebrity gynecologist” at Cedars; I was a PA for a short-lived nighttime soap, and a secretary at a law firm downtown. Most of my friends worked for rich people, too—cutting their hair, typing their scripts, parking their cars, serving their food. Some made amazing money waiting tables at fancy restaurants; the better-looking they were, the more money they made.

At night there was dancing at e.g. the Veil, Circus or, after hours, The Odyssey, an appealingly trashy all-ages club (no booze, but drugs galore) where huge neon-lit cylindrical poles would descend from the ceiling at intervals, lights pulsating, as Prince or the Human League played in a popper-scented haze. We were all high as hell, wearing diaphanous silk chiffon and giant platforms and gobs of eyeshadow, and what was there to question or regret? Youth is for recklessness and pleasure seeking, this was understood. It would be years before the Odyssey burned in a suspected arson fire in 1985.

Screenshot: YouTube

Screenshot: YouTubeBosses might indicate their approval of your work or celebrate your birthday by treating you to sushi in Malibu, or a fancy lunch at Le Dôme (caviar in tiny glass bowls with sieved egg yolk on the side, and duck salad to follow). Already we were in their pockets, drinking their wine. I regret to say that I slid instinctively into the warm sybaritic soup of luxury living and paid no meaningful attention to the truth of the world into which I’d been indoctrinated. The senseless costs, environmental, political, human, of sending caviar halfway across the planet for the delectation of a witless young dope like me went unreckoned. In one’s twenties beauty itself is enough to drive you half crazy, but the lush pleasures of the late 20th century created generation after generation of middle-class strivers with fantasies of discernment (the best Japanese dance music, the best butter) and a lifetime aptitude for building castles in the air.

The Hollywood crowd’s politics in the 1980s was largely ornamental, just as it is now, consisting back then of an antipathy to Reagan, a polite concern for the struggles of gay and otherwise marginalized people, and general regret for the plight of “those less fortunate.” It included writing checks to charities and boundless admiration for singers flying in on the Concorde to perform on “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” and it did not include or even consider anything, philosophical or material, that might diminish the pleasure of your next vacation to Tuscany or your new Alaïa skirt. I wasn’t twenty before I’d thoughtlessly absorbed all these notions. The world was so full of promise, ease and plenty—not for everyone just yet, sure, but bit by bit every problem would doubtless be solved, a better world was coming, unquestionably, inevitably.

Thus the commercial pattern of culture was as it still is established. Our bosses flew first class and stayed at the Danieli, we flew coach and stayed in a beautiful pension with giant wooden shutters but still, we were dreaming their same dream.

Eventually a pitch-perfect account of what was happening would emerge, I recommend it, it holds up immaculately.

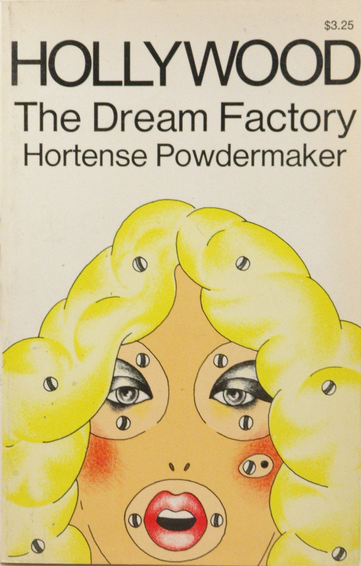

That Hollywood in particular invites and stokes these fantasies on a massive scale has been clear since at least 1950, when the cultural anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker published Hollywood, The Dream Factory—her coinage, and one that has stuck quite as stubbornly as “Tinseltown.” That the author’s name has not likewise stuck is to be regretted. Powdermaker was an original and nimble writer with stone-cold insights regarding “the domination of the business executive over the artist,” and the danger of failing to appreciate that Hollywood has always been more factory than dream.

Powdermaker’s account of job insecurity in the film industry (in 1946) is especially sobering. The real driver of Hollywood culture in the postwar period, she wrote, the most important thing, was “the big salaries and enormous profits.” Only the money ever really counted, so much so that each new project must bring either money, or ruin.

From top to bottom, no one is sure that his job or reputation will continue… there is no security in employment for anyone.

The relationships are highly personalized on the verbal plane, but impersonal on the deeper exploitive and manipulative level.

Seventy years on, nothing has changed. The same air-kissing hypocrisy performed by people terrified of losing their “status”—so clearly documented in Powdermaker’s postwar Hollywood, and so viciously skewered in The Player and Succession—has spread through all of society, down into its deepest tissues.

Long before COVID-19 American politics, art, business, science and the academy, the bedrock of culture itself had already been cracked from end to end with deep professional and ethical fissures based in that same insecurity, the result of putting money first.

Powdermaker thought we could do better.

To say someone is “arty” is a term of opprobrium, while to say he is businesslike is a compliment. Art and artists belong to the extravagances and to the periphery of society. Business and businessmen are the essentials which make the wheels go round […]

This order of importance has no God-given sanctity… It is possible at least to conceive that the artist, who enriches our imagination, deepens our understanding of our fellow men, broadens our experiences and sharpens our sense of moral values, is as important as the businessman.

The cheap, desperate antics of the rich and powerful, hidden away now in their luxury bunkers, or actively endangering the voters of Wisconsin, or singing to the little people about “no possessions”—all these soul-crushingly dreary attempts to assert influence or control, or force an impossible restoration of the status quo ante, are themselves like the magic phrase that jolts you out of a trance.

$120K watches and $10,000 dresses that used to seem harmless or irrelevant are revealed in this harsh new light as irrational, thoughtless, greedy. Against the background of global calamity, conspicuous consumption is not “success,” it is something gross and unwantable.

Ordinary people have only limited influence on politics or finance in the current emergency, with authoritarianism on the rise and corporate power more massively consolidated than ever. But culture itself is instinctively shearing away from money and the power it represents; as the sirens scream through all the world’s cities, the hypnotic power of the dream factory is broken, maybe forever—leaving us with the freshly urgent question of how, and why, to spend it.