For those of us committed to a transnational approach to defending human rights, The Brick House offers a new dimension in cooperative publishing: We’re forming partnerships between artists and writers around the globe to create uniquely valuable new perspectives for our readers. As founding editors of The Brick House, we’re very excited to bring you the first of these efforts, to show you what we mean.

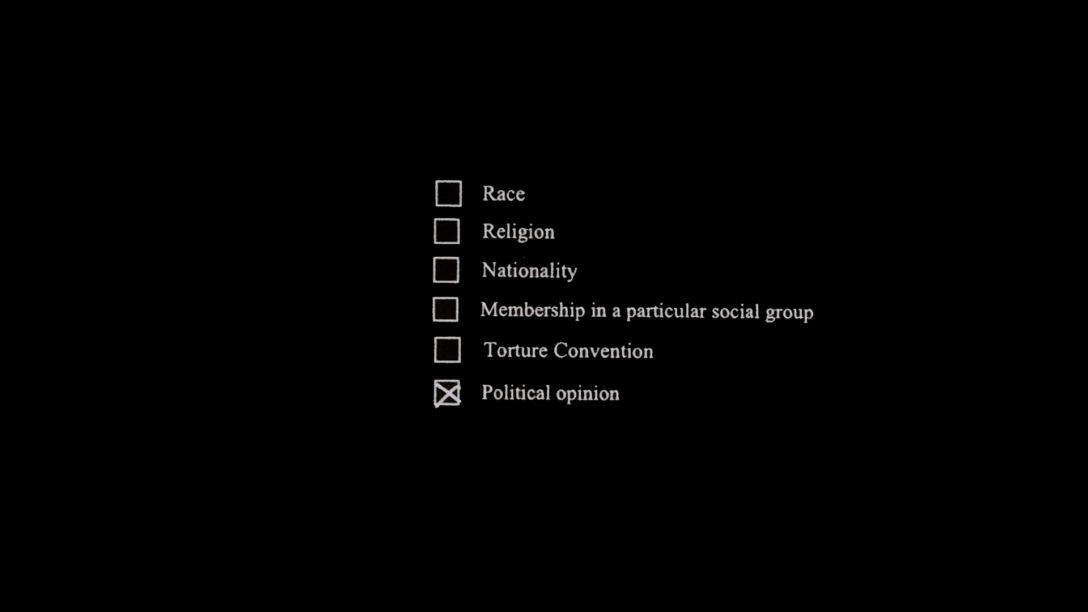

Two Prisons is the first in a forthcoming series of film screenings from The Brick House. Directors Casey Carter and Colleen Cassingham bring us the story of Beijing activist and dissident Wang Zhongxia, who was abducted by police in 2009 on the grounds of “Suspected Subversion of State Power.” He’d printed t-shirts bearing the phrase “free all political prisoners.” He eventually escaped the mainland and applied for political asylum in the US; he currently lives in New York, where he works as a paramedic.

Please join Brick House founding editor Brian Hioe of No Man is an Island in a Q&A with the Two Prisons directors and Wang Zhongxia. This extraordinary short film, just 18 minutes long, is the most compactly moving expression of humanity grieving under the suppression of speech and thought I’ve ever seen, and I hope you will watch it with us.

—Maria Bustillos

It’s not easy to uproot oneself, to have to cut ties with friends and family as a consequence of one’s political convictions. But that’s the fate of political asylum seekers, whether in the US or elsewhere, a process that consigns them to the mercies of one state in fleeing from another.

Two Prisons is a powerful, highly creative reenactment of the experience of Chinese dissident Wang Zhongxia, who fled from China after the death of Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. It’s a highly compelling look into the experiences of a Chinese political dissident who took a stand and paid a price for it, but who is not one of the internationally known names that appear in the headlines of major newspapers. Along with Maria, it was my pleasure to have the opportunity to talk with Zhongxia, as well as Casey and Colleen, who made the film, by video conferencing software.

—Brian Hioe

Q&A Highlights

(full Q&A video appears below the text)

Brian Chee-Shing Hioe: Where did you meet Wang Zhongxia and where did the idea for the film come from?

Casey Carter: I spent a summer in Beijing several years back, while Zhongxia was still living there. He was working at Ai Wei Wei’s studio at the time, and fortunately I met him in passing. But then several years later when he flew here to seek asylum, we reconnected.

And we had a couple of drinks and went out for dinner, hanging out in New York in these first few days of his arrival. And he was very forthcoming in telling me everything that he had been through. And then one night, he basically just described the whole sequence of everything that led him to where he was.

I remember sitting across the dinner table and him kind of looking over through his glasses, staring me in the eyes as he’s telling me all of this shit that he went through. And so it was a really powerful experience for me, and I felt like I wanted to make a film that could have that same sense of intimacy and direct storytelling, while also finding a way to create a more immersive experience of the events within the story. So that was the initial encounter, and the impulse that led to the way that we decided to construct the film.

Brian: Why did you decide to superimpose New York City and Beijing in the film, in reenacting the events that happened to Zhongxia during the arrest?

Casey: We made this film in the first few months that Zhongxia was in New York. He had filed his application for asylum but was unable to work. Essentially all he could do was wait until further notice, so it’s very much this limbo moment. And we were thinking about how to hint at this way of being caught between two different places in two different times, as well as this process inherent in the asylum application—having to explain one’s life in excruciating detail and make a case for political asylum.

So we sought out locations around the city that had some sort of resemblance or could stand in for something iconic about the places in which these major moments occurred in his saga in Beijing. There’s the t-shirt shop that we found in Queens. We went to two separate hotels. One was a “fancy” hotel, and one was like a shitty hotel.

Colleen Cassingham: We spent five or six hours in this grimy, shitty hotel room that’s the setting of the last scene. And we would really just try a whole bunch of different things. Casey would suggest a few things we could film. Maybe Zhongxia will say, “Oh, I remember I used to spend hours every day pacing around this tiny room.” Because he was detained there for 20-odd days. And so then we’d film a whole bunch of coverage of pacing around this tiny room.

I think it brings up the question of performance a bit. What does it mean to reenact, or perhaps, re-narrate the traumas of your past?

Wang Zhongxia: I have considered myself a transparent person for a long time. Since day one, I was doing internet blogging in China using my real name. I consider my experience not only a personal experience, but something that should be made public, to be accessible to everyone. And I don’t mind making it very intimate, inviting people into my head. I think it is even necessary, because this is something already beyond your personal experience. It is about the regime to control a person in the backdrop of political persecution.

Colleen: The title of the film, “Two Prisons,” can be interpreted in a number of ways. On the most literal level, you have the two different hotel rooms that Zhongxia was detained in. Or maybe it’s the physical prison and the mental one, the mental prison of fear that Zhongxia references at the end of the film.

But the interpretation I find most meaningful is the idea that Zhongxia is suspended between China’s security apparatus and USCIS (US Citizen and Immigration Services). He’s at the mercy of both. And one of the things that we hope the film does is to invite audiences to think about authoritarianism and authoritarian politics, not just in China, but also globally in this particular moment.

Brian: Zhongxia, can you talk about the role of Twitter for you, previously as an activist in China, and now as a paramedic in the US? You’ve been posting updates about COVID-19 in Chinese, for a Chinese-speaking audience.

Zhongxia: Twitter is a very important part of my life, I should say that. And I believe my fellow Chinese activists also will say the same thing. Actually, it’s a very profound thing to say because when I was in China, I was under the complete control of the Beijing policemen; not only physically, but also mentally controlled by them.

When I was released from the black jail, I still felt very scared, very terrified. I couldn’t really use Twitter. I was even thinking maybe I would be unable to use Twitter at all, for the rest of my life, because the terrifying effects created by the policemen were so strong.

When I came to the US to seek asylum, I initially still didn’t know what would happen to my Twitter account because just moving from China to the US was a very drastic change. And you feel like you want to just curse China every day, every second on Twitter, because you were suffocated for so long, but you also know it’s not a very healthy way of using Twitter. During the time we were making the film, I was still trying to adjust in terms of using Twitter. I just used it as a personal platform to document my life in the US. And still I used it as a tool, as a Chinese dissident in exile.

But later on, I was advancing my career as a young EMT and then became a paramedic. I’d been documenting my life using Twitter, and when COVID happened, it became pretty significant, political in nature. Right now I feel like I’m comfortable on Twitter. I don’t need to vent politically against China to feel good, but still, if I see something I can criticize, I will say something about China. But right now I’m more focusing on American politics, criticizing the current administration, because I’m paying taxes here.

Brian: Next I wanted to ask about the role of [activist and writer] Liu Xiaobo in the film. He was imprisoned by China and locked away even as he won the Nobel Peace Prize. And he came up quite often in Zhongxia’s story. Right now, during this livestream, we even see that on Zhongxia’s wall there’s a picture of Liu Xiaobo in the background.

Casey: One of the most interesting facts that didn’t make it into the final version of the film is that as a result of Zhongxia’s support for Liu Xiaobo—as well as his action of signing Charter 08, which was co-authored by Liu Xiaobo—as a result of that support, Liu Xiaobo’s wife wrote an open letter in advance of the Nobel ceremony inviting numerous friends and family to accept the Nobel prize on behalf of Liu Xiaobo, since he was in prison at the time. And Zhongxia’s name was included on that list. And the people on that list were more or less rounded up and detained, so as to keep them from having access to this political gesture of accepting the prize on behalf of Liu Xiaobo.

Zhongxia: Yeah, I was one of the 144 guests invited by her to go to Oslo to accept the Nobel Peace Prize for Liu Xiaobo. But of course, this is only a political statement. No one will really go there because the moment she released this letter, everybody on that letter will be put on the blacklist, no fly list.

Even two years later, in 2012, I was trying to get on board a flight to Myanmar for a personal visit. I found out I was unable to leave. I had to fight with the Beijing police department who put me on that blacklist for international flights. It was two years before I finally was allowed again to go abroad, to fly out outside of China for a personal trip.

Casey: The one other thing I would add about the significance of Liu Xiaobo in the film specifically is, from our point of view, trying to create some idea of this relationship between the big public figures, and the slightly more anonymous – I think Zhongxia described himself at some point in our conversation as, “I’m just a little guy.”

Colleen: Baby activist.

Casey: Just someone who has the courage and determination to put themselves forward, but does not have the audience or the impact as someone like Liu Xiaobo, whose very name is part of a series of diplomatic gestures surrounding the Nobel prize and so on. So it’s like this relationship between what’s happening at the highest levels of diplomacy and what’s happening at a very personal level, and a “baby activist’s” personal experience.

Brian: Zhongxia, how did it feel reenacting these painful experiences for an audience?

Zhongxia: I wouldn’t say I enjoyed it, because to relive your painful experience is not a very pleasant thing. But I feel like I agree with their way of making the movie. Honestly speaking, initially I was just thinking, “Oh, I need someone to do something with me because I just arrived in this new country.” I was prepared to live here for a very long time, even forever. So I have no job, no social connection, nothing. So I was very glad I can do something with someone, and especially this—this is something that’s pretty meaningful… I saw it as some very special psychotherapy. It was difficult for me, especially in a language that is not my first language. But the more we did it, the more I felt like: I just need to do this. I need to finish this project.

Brian: Can you talk a bit about how you became a political dissident, for lack of a better word? And then your experience of fleeing to the US in terms of the substantive process of that?

Zhongxia: I was just a regular student. I got into Renmin University, and during university, I had a lot of time to go online. So I found out that there’s a firewall, the Great Firewall, basically. This is a very expensive, very sophisticated system the Chinese government built to filter the information coming inside China. So I found out I was living in a designed environment, in terms of getting information.

I think it is a very natural thing to be angry. You should be furious. But apparently my Chinese classmates, my friends, they didn’t care about this. I told them the truth, that there’s a thing called the Great Firewall that controls the information, in terms of what we can see, what we can read. And they just feel: yeah, that’s okay.

So I started blogging. I started moving around information, whatever the Chinese government didn’t want us to see, I just moved it into my personal blog. So it was a very naive action, but that was my initial political activism. I didn’t even express my own original opinions. But this very simple action already put me in a very dangerous situation. So I was approached by the Chinese state security agents after my trip to the US in the 2007, visiting New York City for Model UN, which was the first time I went outside China.

A soon as I got back to China, they approached me and they scared me. They interrogated me in an office in our economics department in the university. And they monitored me for closely for one year, my final year in the university.

They asked me to write a kind of confession letter, one letter every month. They came to visit me on the university campus to collect it, and in each letter I would have to say what I did during this month, what I thought about, and what I learned.

Of course, they don’t care about what mathematics or economic theories I learned. They want to hear political correctness, which in China means how I love my country, how I love my government, how I shouldn’t meet certain people, how I should avoid certain, bad websites, those kinds of things.

At the end of that year, the Charter 08 manifesto was published on the internet. This document was collectively written by 203 Chinese intellectuals and scholars, including Liu Xiaobo.

Even though I had just had one year of close monitoring from the state security agents, I saw that letter and I couldn’t agree more. And I saw the names on it – people like Liu Xiaobo, names I’ve known for a long time. I admired those people as a young student.

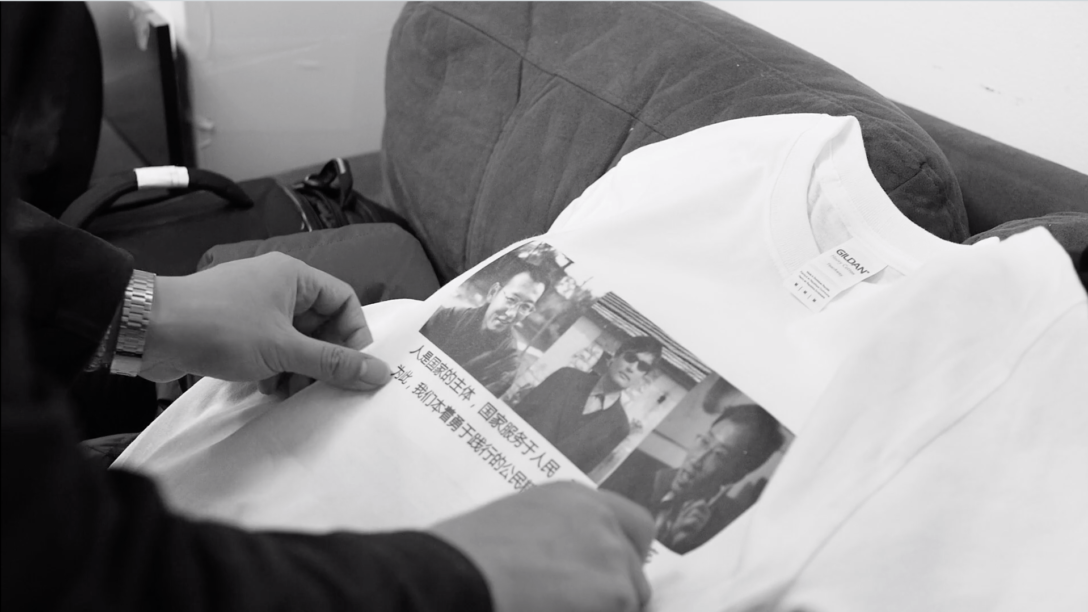

So I still put my name on that document. I also decided to make some t-shirts with Liu Xiaobo’s photo and photos of two other famous Chinese political prisoners.

Zhongxia: But the biggest thing is, I made the t-shirt public. If you only make them and put them under your bed, no one knows about it. It doesn’t exist. That’s why these things are important.

I published the photo of the t-shirts on my social media, and I was very conflicted. Part of me was very proud of my action, and also part of me got really scared, because I knew this was going to invite even more persecution. And then those persecutions happened.

They detained me in that same t-shirt shop. They told the shop owner to lure me back to the shop to give me a receipt. And when I went back they captured me in that shop and interrogated me for seven hours, including a home search. They took my laptop away… [to this day], they never returned it.

And after that I was on their monitoring list. I was constantly harassed. And every year during the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, I would be pulled into some kind of restriction, either house arrest or hotel arrests , so they could control me, isolate me, make sure I don’t get on the internet and don’t meet the other fellow dissidents or activists.

So when they announced Liu Xiaobo was the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, they just rounded up all the people who are related in this matter to put them in house arrest from October, when the winner of the Nobel prize in announced, until December, when they hold the ceremony.

And I was, of course, one of them, but I escaped my home, so they didn’t trap me into house arrest. I was just moving around the city, going to a friend’s house to avoid detention.

But during that time I was still writing articles to praise Liu Xiaobo, using Twitter as a political tool for activism. And I was even interviewed by major US news outlets right before the Nobel ceremony. And after that interview I was captured by the Beijing policemen. They intercepted my taxi, and that’s when the 23 days of detention in the hotel began.

Brian: Could you talk a bit about the process of fleeing China, since that’s not touched on directly in the film?

Zhongxia: After the 23 days detention in 2010 I felt very tired, very damaged. So I retreated from political activism. I gradually tried to find some so-called normal life pattern in China, to find a job, to have a career. I never thought of fleeing China or seeking asylum in a foreign country.

But in June 2017, suddenly the news came from a friend that Liu Xiaobo is in the final stage of liver cancer, while in prison. And we all held out hope for some kind of miracle, but finally he died on July 13th, 2017.

So I started thinking about, what should I do with my life? Because Liu Xiaobo is basically the major reason why I wanted to stay in Chinese political activism. Because of his personal history, his bravery, and his charisma. We considered him the leader of the Chinese dissent. If he was alive, he would be a free man in China. We were hoping when he got out of prison at the end of his term, which would have been this year, in 2020, that he would put pressure on the Chinese government to help the democratic transition. Sort of like a Dalai Lama type person, since he has the Nobel Prize. We were holding onto that—that was a support to me in my life in China. I was leaning on that. When he died, I found this whole thing became meaningless for me.

So I started to file a visa application to the US embassy. I was thinking of getting out, and also I can see the Chinese government already doing more societal control. So the situation in China would be getting worse and worse, and the reality proved my theory. I got lucky. I got a tourist visa. But I was still uncertain and worried about if I can get out of China.

So I didn’t book a flight from Beijing to New York City. I traveled to Shenzhen, which is a Chinese city in the very south bordering Hong Kong. And I didn’t book any international flights because I thought the moment that I book a flight, then the Chinese government, the police will know it and they will put me on a blacklist, assuming I was off it already.

And then I planned to travel from Shenzhen to Hong Kong by boat, but unfortunately the boat agents didn’t allow me because of my visa. So I hired a minivan to take me from Shenzhen to Hong Kong by land. And luckily the Chinese policeman at the Shenzhen checkpoint allowed me to go out. So apparently I was not on the blacklist.

When I arrived at Hong Kong international airport, my flight was already boarding. I almost missed my flight because I had wanted to delay buying the tickets as long as possible. So I almost missed my flight, but I made it. And then, a layover in Manila, and then another layover in Vancouver and then, I arrived in New York City.

Brian: What sort of responses have you gotten to the film? I’m particularly curious about responses from Chinese people. I know the film was screened in Hong Kong last summer.

Zhongxia: A lot of my friends are from the internet, and I have quite a few followers. And the Chinese people are the ones that are most interested in the movie, and they keep asking me: when can we see the movie? When is it going to be available on the internet?

Casey: So far, the film has screened at a few festivals this year, which have all been digital because of the pandemic. But the two most compelling screenings that have occurred are the only two that have occurred physically.

The first was a screening of an early cut at the UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art in Brooklyn, which was actually the home for the production of the film. Colleen and I were in a fellowship program there when we made this project. And that was a very powerful screening: the first time anyone had seen it, and Zhongxia invited Zhou Fengsuo.

Zhongxia: Zhou Fengsuo is a very famous Chinese. He was among the most wanted student criminals back in 1989 as one of the student leaders in the Tiananmen protesting movement. And then he sought asylum in America and became a political refugee in America. And until today he is still doing democracy activism.

He knew me even before I came to the US, of course, through Twitter. So he knows me as a person, and when I arrived in America, he was very supportive. He told people like, “Hey, we have a new guy who arrived here. Please take him to dinner, treat him at a restaurant.”

When I told him that there’s a film about my experience, he was very supportive. I was very honored to have him at the first screening because he is like a person walking from history. Because he was a person at the massacre that happened in 1989 in Tiananmen Square. And all my experience, all my actions are based on that moment.

Casey: The second screening was in Hong Kong last summer, when Hong Kong was completely overtaken by protests, following the proposed extradition law.

The majority of the audience members were friends of Zhongxia’s from China. They had traveled to Hong Kong and were all wearing this t-shirt [holds up t-shirt with young Zhongxia’s face on it], which is an old picture when Zhongxia’s hair was much longer, looking very handsome. And they had not seen him in a couple of years and they hadn’t seen the film, and Zhongxia was of course unable to be there. So it was a very powerful moment of connection between the life and the friends that he had left behind.

Zhongxia: Those friends are real friends, because traveling to Hong Kong from Chinese cities is an expensive thing to do. And also they are not political activists at all. They support me, but they don’t do it themselves – they are regular Chinese young professionals. But this screening happened and they still were willing to do this just to support me. So I feel like, yeah, it’s very moving.

Brian: What’s next for the film?

Colleen: Now that it will be publicly available, it’s the best case scenario for us. Had COVID not happened, we might have played more festivals, but because the in-person experience isn’t possible anymore that’s less of a priority for us and it feels more urgent to instead just bring it to as many people as possible. Especially as the crackdown in Hong Kong continues, and even in the context of the upcoming US election. And I can’t think of a better partner than the Brick House, whose values of protecting free speech and a free press align so perfectly with our film.