There’s nowhere more alone than in the middle of a social movement, sometimes, feeling like you’re up against the world, with nobody who supports you or understands you. Even so, for a long time, I didn’t really get the point of “solidarity.”

Political involvement of pretty much any kind is as frustrating as it is lonely. As a younger activist, I often saw attempts to share experiences or skills between struggles. But they seemed so insubstantial to me. I often felt people would come away with only a superficial, simplistic understanding of a social movement not their own. Or alternatively, that they were learning nothing of practical use from activists involved in a totally different situation, cause, or country. What’s the point of sharing nothing more than a vague sense of sympathy? It seemed like a waste of time.

My views have shifted on this point, though, over the years. Maybe sympathy is enough; solidarity from abroad, for example, can be very empowering.

I came to realize this when in 2017, I interviewed nearly a hundred Sunflower Movement activists to learn how they felt about linkages to international social movements. Many of them discussed the powerful moral support they’d felt from abroad, due to expressions of solidarity. I came to realize the importance of this feeling of connection, however imperfect, whether in Taiwan or elsewhere.

Recently I translated an English text for a museum exhibition on the history of the Taiwanese democracy movement. Part of the text compared the sense of solidarity from abroad to something like the Force in Star Wars—feeling like you’re part of a larger, more universal power, a maudlin idea that rendered poorly in English.

An easier reality to grasp is that in this fractured world it can be very hard to feel much of a connection with any “foreign” place. It’s far easier and more instinctive to impose your own frameworks on other places, other countries, other people.

The recent American presidential elections provide a stark and troubling example of that kind of natural human provincialism, of seeing the world through a too-narrow lens. For example, some well-known advocates of political freedoms in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China have taken to idealizing the outgoing American president Donald Trump for what they perceive to be his strong stance against the current Chinese government, though it’s quite obvious that Trump is no friend to freedom in his own country. He has indeed violently undermined American democracy, refused to accept the legitimate election results or to commit to a peaceful transition of power.

Even so, certain progressives in Taiwan or Hong Kong, and Chinese dissidents such as artist Ai Weiwei and former Tiananmen Square student leader Wang Dan expressed support for Trump’s reelection. Worse yet, some embraced conspiracy theories wildly speculating that the election was stolen from Trump through Chinese election interference; others have suggested, along with US Republican conservatives, that contemporary protests in the US such as the Black Lives Matter movement were engineered by China to undermine America.

Ironically, these accusations mirror the Chinese government’s denunciation of the recent Hong Kong protests against the deterioration of political freedoms in that unfortunate country. The Chinese government has steadfastly refused to confront the real and obvious domestic discontent in which the protests originated, falsely claiming instead that the unrest was incited by the shadowy manipulation of western powers from abroad.

This weird embrace of Trump, which truly confounded US progressives, reflects a particular kind of political short-sightedness; a failure to apply one’s own convictions and logic outside the narrow confines of one’s own polity. Leading Hong Kong protest figure Joshua Wong, for example (who was jailed some days ago), drew significant flak after speaking at an event discussing Black Lives Matter; in certain circles Wong was praised; in others, he was criticized for having betrayed the Republican allies of Hong Kong. Because US Republicans have repeatedly proved themselves inimical to the democratic ideas supported by Black Lives Matter, as they are by the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong such as one person: one vote through their decades-long campaigns of voter suppression, gerrymandering and disenfranchisement, the US left threw up its hands at even the idea of pro-democracy US Republicans concerned about the loss of freedoms in Hong Kong.

States, when they do back movements, usually do so for their own purposes, whereas solidarity happens for human reasons, and originates in egalitarianism and goodwill, however clumsily and ineffectually those convictions may be manifested. There is as yet very little that far-flung social movements can offer one another directly. But even so, a mutual desire for intellectual and political freedom can and should be shared, because that sharing gives heart to every struggle for equality and freedom.

Last year, for example, during the protests, Taiwanese sent gear such as safety helmets and gas masks to Hong Kong. Though the threat of authorities finding out what routes Taiwanese were using to send equipment to Hong Kong hung over those efforts, and though a limited amount of aid could be provided, the knowledge of this solidarity spread over the world to progressive activists in Europe, the US and Latin America as well as throughout Asia, planting a kind of flag in people’s minds.

One cannot define, exactly, what solidarity specifically does for a cause. That’s why many people are so dismissive of the idea. But there’s also a way in which these are the only ties that genuinely bind, since they are entirely free of self-interest. Solidarity is hard to come by, but seen through a certain lens, nothing can replace it.

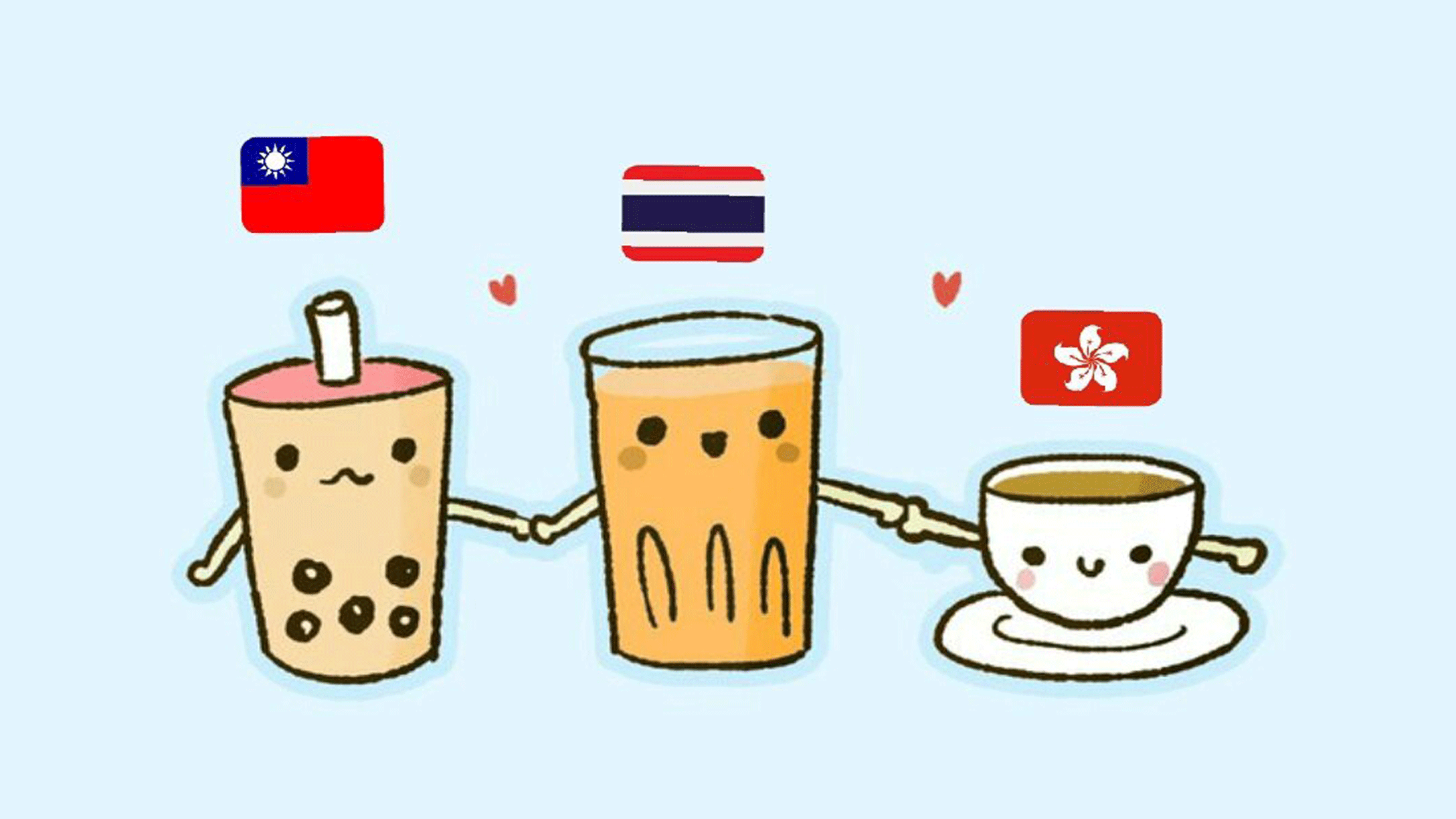

The Milk Tea Alliance provides an interesting example of this kind of disinterested solidarity. Netizens from Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong began to align after nationalistic Chinese Internet trolls attacked a Thai actor for his girlfriend’s alleged support for Taiwanese independence.

There’s no immediately identifiable source of the Milk Tea Alliance, though certainly there are transnational bonds between people with democratic values in Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong, against nationalistic netizens from China. Thailand doesn’t face the threat of China in the way that Taiwan and Hong Kong have long shared. Yet Thai netizens, who are suffering under an autocratic government, made common cause with people in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Afterward, Thailand saw historically unprecedented youth-led protests against the institution of the monarchy which, in some respects, followed the pattern laid down by Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Taiwan and Hong Kong have expressed solidarity with Thai protests. But the response of authorities in Thailand has been to try and claim that this sharing of tactics is evidence that the protests are not organic, that protesters are backed by mysterious outside forces, just as Hong Kong authorities claimed that Taiwan and the US had stirred up protests there. In Singapore, authorities targeted activist Jolovan Wham for hosting an event in which Joshua Wong Skyped in by video conference as a speaker. The rigid response of authoritarian regimes suggests that there is perhaps more to solidarity than meets the eye. There’s a transnationalism to authoritarian actors as well.

I don’t know how movements across disparate borders, facing different but parallel challenges, can draw from each other. The Milk Tea Alliance phenomenon, which began online, begins to show the way. The Brick House in itself a project in this vein, as well, with founding member publications ranging from Asia to Africa, and more to come as we grow. Even if it’s not immediately clear as to why these publications would align, there are more and more of these transnational networks forming among publications–not so surprising, perhaps, since media everywhere is facing similar threats from powerful corporate interests. And if something like the Brick House is to survive, it needs to grow, and to develop further, and for more people to add their ideas to it and see where it can take us.

In my view, as a translator, the biggest challenge to transnational solidarity is language; communicating across different contexts often requires translation into English, which is, for good or ill, the lingua franca of the world, and quality translation is painstaking and expensive; Google Translate is of no real use to a non-native speaker of English. It’s harder still to bridge different political and social contexts between languages. The infrastructure of the Internet doesn’t easily allow for transnational efforts; large gaps persist between local, native discourse, and discourse that takes place in English, in any given place.

But even knowing that is a start.

Perhaps what disparate movements are doing best is simply drawing legitimacy from each other, even as the authoritarian governments they are confronting seek to delegitimize each other. It reminds me of a Chinese idiom: a story about fish on dry land sharing their spit to help keep one another from drying out. Maybe it’s a bit like that.