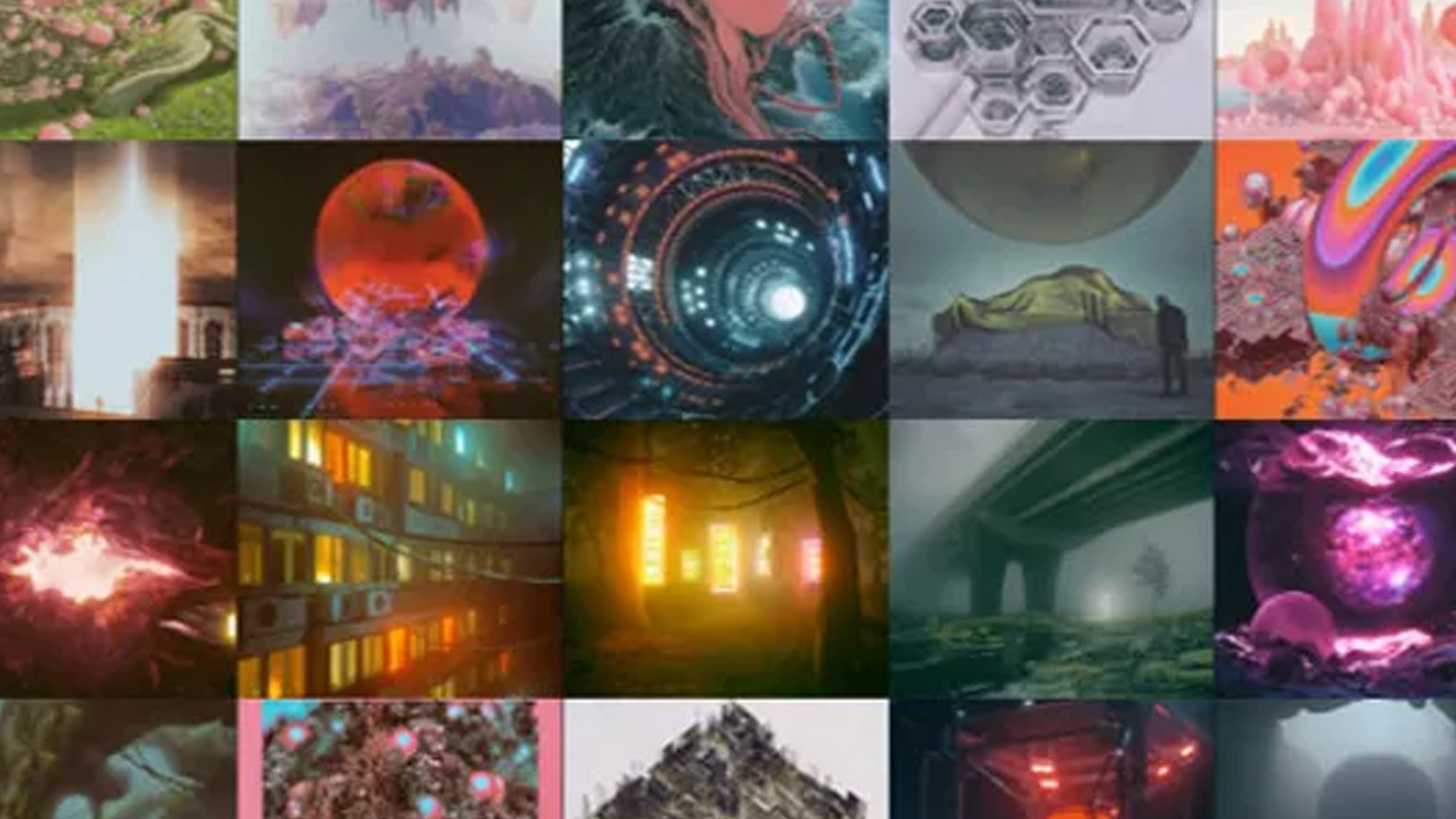

The tension between art and wealth underwent a peculiarly violent spasm on Wednesday when a tokenized digital collage by Mike Winkelmann, the artist and filmmaker known as Beeple, sold at Christie’s for $69.3 million. “Everydays — The First 5000 Days” is made up of 5,000 images, one produced each day by the artist over the last 13 years. The authenticity of the resulting digital mosaic, 21,069 x 21,069 pixels square, is guaranteed by a “non-fungible token” or NFT, a new method of verification made possible through blockchain technology; a kind of “signed limited edition” generated through the web.

On the “Today” show, NBC’s Kerry Sanders had a ball expressing amazement that anyone would pay a fortune for intangible artworks, or for something you can already see or experience for free. Well, you can read a translation of the Magna Carta for free at the National Archives, but if you want a copy seven centuries old for your very own, it will set you back about $25 million. There’s nothing new about the allure of rarity or uniqueness; why do certain Star Wars figurines or baseball trading cards or Sung Dynasty vases command outrageous prices?

Why do people want things, we might as well ask (I’ll wait).

Beeple was already a well-known name in commercial art circles, having collaborated with musicians and design firms such as Louis Vuitton, Justin Bieber, Katy Perry, Nicki Minaj, One Direction, Eminem and Flying Lotus; he wasn’t some rando in a basement whom nobody had ever heard of, and it isn’t surprising that his work would fetch high prices. What’s got critics in such a lather, seemingly, is the sheer gold-rush weirdness of crypto-denominated digital art, coupled with valid fears regarding the carbon footprint of the blockchain technology that enables it, though the operations of the broader internet—including Facebook and Instagram, Google, Amazon, Netflix et al., plus banking, credit card, forex and Wall Street transactions—dwarf the emissions of Bitcoin and Ethereum.

The furor over the Christie’s sale of Beeple’s NFT is focusing on the wrong aspect of the story. It makes far more sense to question how and why money has flooded into the art world at such a frantic pace over the last four decades, as global income inequality grew more and more acute.

The key benefit of NFTs is simple: public blockchains produce incorruptible records that anyone can see on the internet, so they’re ideal for marking collectibles. It’s literally impossible to forge or counterfeit the credentials conferred by an NFT, because they’re stored in public across thousands of computers around the world, all of them holding identical copies of the same records.

12 years after its founding in January of 2009, blockchain technology is taking shape as a global force for validating all kinds of transactions. Big banks are no longer skeptics. JP Morgan’s chief executive Jamie Dimon dismissed Bitcoin in 2017 (“a fraud,” “worse than tulip bulbs”); now his firm is playing a key role in installing Ethereum as a linchpin of interbank information sharing.

The two leading blockchains, Bitcoin and Ethereum, are burning through far too much electricity at the moment, it is true: the energy-intensive network competitions required to run the earliest blockchains, known as “proof of work,” require a computational arms race that essentially rewards the participants burning the most power. But already, today, energy-efficient alternative public blockchains based on a new technology known as “proof of stake” are available, including Polkadot, Cosmos and Avalanche, and Ethereum is not far behind.

“The energy consumption of a single transaction on Bitcoin or Ethereum is stratospheric at the moment,” Cornell computer science professor and Avalanche co-founder Emin Gün Sirer told me. “Proof of stake stands poised to change all this drastically… [it’s] somewhere between a million to a billion times more efficient than Proof of Work.”

(AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

In 2019 Jeff Koons’s 1986 Rabbit, a three-foot-tall stainless steel representation of an inflatable bunny holding a carrot, sold, also at Christie’s, for $91 million—about $22 million more than “Everydays.” If you want to hear some real art-world hokum, consider Koons’s explications of his stainless-steel rabbit.

“It is very seductive shiny material and the viewer looks at this and feels for the moment economically secure,” the former commodities broker babbled. “It’s most like the gold- and silver-leafing in church during the baroque and the rococo. The bunny is working the same way. And it has a lunar aspect, because it reflects. It is not interested in you, even though at the same moment it is.”

Vast and sudden fortunes had been minted throughout the 1980s, when Rabbit hopped onto the scene. In March of 1987 a Japanese collector bought one of Van Gogh’s “Sunflower” paintings for $39.9 million, nearly quadrupling the record price for a painting sold at public auction. The floodgates opened after that, with the ultrarich pouring more and more of their egregious surplus into art, and—in sharp contrast with the curators acquiring art for museums, in the interests of cultural preservation—these nouveaux riches favored artists expressing views and an ethos sympathetic and even flattering to their own.

Among the highest-priced artworks ever sold are several produced by Andy Warhol, an artist and celebrity whose affinity for wealth, like that of Jeff Koons, was more concretely discernible than any meaning that might be attached to his work. In the New York Review of Books in 1982, the art critic Robert Hughes, who saw what was coming, memorably compared Warhol to Reagan:

How can one doubt that Warhol was delivered by Fate to be the Rubens of this administration, to play Bernini to Reagan’s Urban VIII? On the one hand, the shrewd old movie actor, void of ideas but expert at manipulation, projected into high office by the insuperable power of mass imagery and secondhand perception. On the other, the shallow painter who understood more about the mechanisms of celebrity than any of his colleagues, whose entire sense of reality was shaped, like Reagan’s sense of power, by the television tube. Each, in his way, coming on like Huck Finn; both obsessed with serving the interests of privilege. Together, they signify a new moment: the age of supply-side aesthetics.

In comparison with the flat, affectless works of Koons or Warhol, Beeple’s supercollage is brimming with cultural and political resonances and references which, whether you care for his style or not, at least provide a lively, colorful record of the last thirteen years, including a lot of darkly salacious commentary on the Trump administration. He is modern, accessible, associated with young musicians, and sympathetic to crypto. Small wonder that the recent explosion of crypto wealth found its way to him.

David Bowie once explained exactly how new forms are appropriated by the institutions of “high art” in a 1996 discussion of graffiti artists Kenny Scharf, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat on Charlie Rose. Why should these three have been plucked from the “sea of signers” then working in New York, and anointed as geniuses?

“It behoves the art establishment to elevate them to a higher plateau as fast as possible, to make them unavailable, aesthetically, to a low art market,” Bowie observed mildly. “[The art establishment] extends its parameters to capture the new thing and elevate it from low art to high art—successfully enough to increase the commerce proposition that goes along with it—and to consign the idea of art to a particular world.”

The real takeaway from the current tempest regarding art-world NFTs is that the pas de deux between art and money will persist, streaming through whatever forms evolve to serve its purposes: stainless-steel rabbits or ancient Greek pottery, oils on canvas or digital mosaics. Considered from this perspective, NFTs are nothing more than a new cup in which to collect the flow.