Studying with the writer George Saunders is like reading his fiction; you can’t get away with your usual dodges (whatever deficiencies you may be trying to conceal, whether of craft, ethics, scholarship, or general human awareness and compassion). His scalpel is so light and so sharp, and so deftly wielded, that your psyche comes out all dissected and arranged into neat pieces in front of you before you even realize what has happened. The trick of it is that he somehow very gently causes you to bring your own self to account.

This is by way of saying that Story Club, the Substack newsletter that George recently launched, is good. It’s like taking a class from him (literally, and I know this, because I took one once). The paywall goes up soon, subscriptions are $50, and there’s a lively comments section on the associated website. It’s meant to be for writers, but anyone will like it, I think.

In yesterday’s newsletter, “Influences“, George invited readers to do an exercise (“a bonus, parenthetical exercise, just for fun, designed to push you into a wonderfully nostalgic holiday frame of mind.”) I’m writing to urge you to try it, because my results were kind of astounding. After nearly two whole years of nonstop emotional distress—like this constant psychic tinnitus—the exercise is one of the only things that has successfully guided my mind out of the asteroid field of the pandemic and related disasters, so that I could more or less hear my own thoughts again.

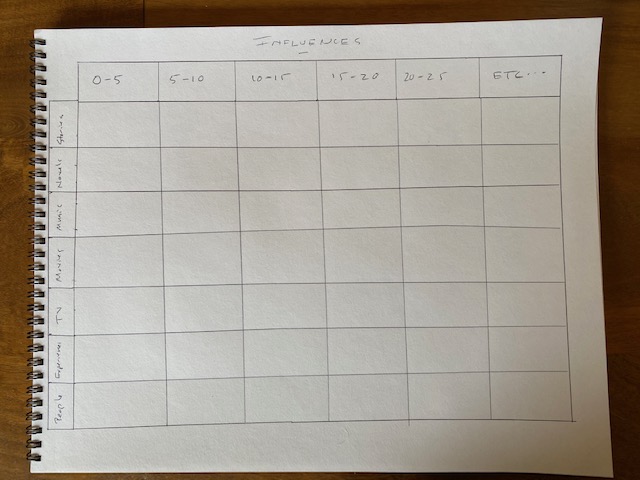

It’s the simplest thing, really!! Deceptively so. All you have to do is fill out a grid on a piece of paper.

Get a big sheet of paper (or set up a spreadsheet) and construct a table. The column headings should mark the years of your life – the first column should be labeled “Birth to 5 years old,” and every column after that should span five years. (“5 – 10 years old,” “10 – 15 years old,” and so on, all the way up to your current age, there across the top of the page.)

The six rows of the table should be labeled as follows: “Stories/Novels/Music/Movies/TV/Experiences/People.”

[n.b. That’s seven!!]

George says you should fill out the grid square by square, in order, to jog you gradually and expand your access to the evolution of your mind. I’m writing a novel, and this sounded cool, and useful. But far from being a “writing exercise,” an incredible thing happened a few minutes after I began filling out the form: a long-dammed place in my mind burst open, and memories began pouring out in uncontrollable cascades.

I hadn’t realized how the isolation and sadness and loss of the pandemic had made me hole up, even on the inside. How I’d lost touch with my own life, just in the daily process of “keeping things together,” navigating the constant state of emergency that has overwhelmed most everyone I know, month after month. One stopped telling people about one’s day because what had it been but panic and the avoidance thereof, plus mourning, laundry, and baking bread in a pot?

The grid brought me a pair of red leather sandals, in which I once posed at the age of four or so, and Merrie Melodies before the movie, and falling asleep in my pajamas in the back seat at the drive-in theater, the soundtrack crackling from lunchbox-sized metal speakers clipped to the car windows. My dear Michael playing the piano in his plaid short-sleeved shirt; The Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo taking the stage in their gorilla costumes at the Golden Bear. Fred Astaire dancing (and the Cuban accents of my mother, once a dancer herself, reverently pronouncing his name); the soft matte texture of the dark blue paper covers of a Spanish textbook for children at my grandparents’ house. Romance, dimly apprehended via The Witch of Blackbird Pond, a library book with a paper slip affixed to the inside cover and stamped with the appointed date of return. The delight of being given the task of shelving books at the library myself. A hot, crisp chicken croquette at a fancy French restaurant in Caracas nearly half a century ago, and the rose corsages my mom and I were given when we arrived there. My late brother, describing a weekend in EST training, and how he’d surprised himself by remarking that something was “silly”—a word he’d never used before, he said, and that was true and I never heard him say it again.

Batman and Davy Jones, George Jetson and Elizabeth Montgomery, don’t touch that dial, it was a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow. Bodysurfing at San Elijo. Glamorous Pan Am “stewardesses” wearing helmets. A small carton of chocolate milk. The contours of my life swelled out and expanded like a Japanese paper flower dropped in a bowl of water.

George isn’t much of a food guy I would say. I on the other hand always loved not only food and cooking, but beautiful glassware, candles and silver, plus furniture, clothes and interiors, though I deeply regret my love of luxury now. I added a line for food experiences to the grid. The coldest, most velvety coconut gelato, also in Caracas. In Rome, a ruinously expensive ice-filled glass of coke on a roasting summer evening in 1977, and worth every lira. Falling in love with food through literature, too. What was a sack posset, what did truffles taste like, what was this wonderful meal, “high tea”?

A line for clothes. Like I said I am ashamed of this now but the prompt asks you, what once filled you with delight? A dove-grey Japanese pinwale corduroy shirt with thick padded shoulders, it snapped up tight as a corset. A red and white polkadot Moschino dress with a black ruffle underneath. A black silk velvet opera coat with an ice-blue satin lining. The iridescent midnight-blue-and-amethyst trousers my boyfriend kept stealing in the 1980s, though admittedly they looked a lot better on him. One for textures; the nubbly brown fabric of the sofa in my parents’ apartment when I was just a baby.

A line for plays. Most recently Leopoldstadt at the Garrick Theatre (during the lull in the pandemic) which was crowded with eager theatergoers not all of whom were wearing masks, aside from which those of us who thought we’d be enjoying an evening of drollery and fizzing wit were in for a fucking surprise, let me tell you. (It’s a fantastic play and everyone should see it, though.)

Everything we’ve loved is a literary influence, George says.

The point is really this: to write a good story takes everything we have and everything we are. We tend to think, “I am in control here, and will honor that in which I have come to love and believe, about writing and art and life.” But, in my experience, that is a too-controlled and too-controlling mindset, saying, as it does, that you, the writer, will decide what is needed when, in fact, it’s the story that is going to decide how much is needed. And what will be needed, if the story is going to be good, is: everything, all that you are, even those parts you don’t like or usually exclude.)

So… please fill out the grid. This exercise brought me back to the examined life I guess I could say, and it was very healing. Thank you, George.