Western media’s focus on the war in Ukraine is like a giant fireball in comparison with the Bic lighter flame of interest in violent conflicts elsewhere in the world, and this contrast is often attributed to plain racism. “Blond-haired, blue-eyed” Ukrainians are far likelier to find sympathy among Westerners, it’s said, than are the brown-skinned victims of violence in Yemen, Syria, Palestine, India, Kashmir, or Ethiopia. But there is an additional, immediately actionable explanation for the stark difference in coverage: Western media audiences had a high and constant volume of direct exposure to real live Ukrainians for years before Russia attacked them. This is a signpost for journalists who wish to draw attention to events taking place far away from wherever they may be.

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy was widely admired, particularly in the US, beginning with his refusal in 2019 to bend the knee to Donald Trump’s flagrant corruption (“I need you to do us a favor, though.”) A less principled Zelenskyy could conceivably have agreed, at Trump’s behest, to tell all kinds of lies about Hunter Biden in order to get hold of the military aid that had been promised to his country. Instead, Zelenskyy’s repudiation of Trump and his Putin-allied henchmen created a well of sympathy for Ukraine so deep and abiding that no amount of old TV footage of the former comedian telling coarse jokes, or even dancing in lace-up stiletto boots, could diminish it.

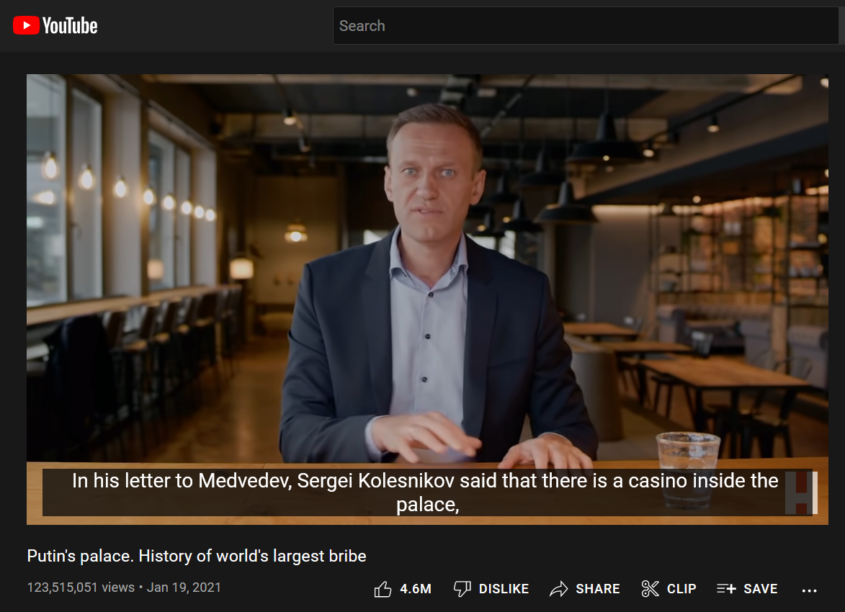

screenshot: YouTube

screenshot: YouTubeThe loud, witty, forthright and intelligent media of the Russian opposition has long given a substantial boost to Western interest in both Russia and Ukraine. The daring investigative exploits of Alexey Navalny, including his team’s exposé of Putin’s Palace, and his unforgettable interrogation of his own poisoner; Masha Gessen’s heartrending accounts of friends blown to the four corners of the earth, which appeared in the New Yorker; moment-by-moment military, cultural and philosophical translations, ruminations and updates from Kevin Rothrock of Meduza. All this, too, shows that journalism succeeds to the degree that it directs the spotlight on those most deeply and immediately affected.

When it becomes clear that the people in another nation are only people like oneself, their “foreignness” melts away, so that their situation can be judged fairly. But if viewers’ understanding is mediated by what Jake Tapper or Christiane Amanpour thinks of someone, or thinks of asking them, then that subject’s chances of evoking empathy and understanding can’t help but be lessened, watered down.

It’s increasingly obvious that every aspect of transnational media benefits from this perspective.

In his 1946 book How to Be an Alien, George Mikes described the peculiar condition of “foreignness” better than any other account I’ve seen.

I have been an alien all my life. Only during the first 26 years of my life I was not aware of this plain fact. I was living in my own country, a country full of aliens, and I noticed nothing particular or irregular about myself; then I came to England, and you can imagine my painful surprise…

I spent a lot of time with a young lady who was very proud and conscious of being English. Once she asked me—to my great surprise—whether I would marry her. “No,” I replied, “I will not. My mother would never agree to my marrying a foreigner.” She looked at me a little surprised and irritated, and retorted: “I, a foreigner? What a silly thing to say. I am English. You are the foreigner.”

War reporting is necessarily bedeviled by questions of “foreignness,” of “Us” and “Them.” But who is the “other”? There is only and ever an “Us,” there is no “Them.” There’s no such thing as a foreigner. Those who can get that obvious fact into our heads and hearts are more likely to produce fair and intelligent coverage.

Where are the people—not only state actors and politicians but satirists and poets, activists, doctors and nurses, teachers, restaurateurs and musicians, developers and sports figures—who will give us intimate and immediate portraits of ideas and values, of life lived day by day? Can Western journalism take the lesson of Ukraine and run with it?