War broke out with Iraq just as we were on our way to a dinner with, of all people, Henry and Nancy Kissinger at the River House.

Tina Brown, The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992

In general it’s best to avoid anybody who’d have dinner with Henry Kissinger, but I still recommend this weird, sad book. Tina Brown took over at Vanity Fair four decades ago, age thirty, armed with an impishly mean sense of humor and a real genius for flattering rich, powerful, awful men. She arrived in New York fresh from a star turn at the Tatler, whose ho-hum gossip pages about London’s aristos and intellectuals she’d remade with pizzazz, cheek and intelligence. Then Si Newhouse—the culturally ambitious chairman of Condé Nast, who’d bought the Tatler in 1982—hired her to resuscitate the ailing Vanity Fair… and she did, so far as the business side went. With the “high-low” formula she developed (“We give intellectuals movie star treatment and movie stars an intellectual sheen”) Brown eventually took the magazine from a $30 million annual loss into the black, with profits of millions, and hundreds of thousands of new subscriptions.

But Mike Judge couldn’t have written a better parody of the big-haired and bejeweled, jet-set, fatcat, red carpet, Met Gala, death-squad-funding, AIDS-failing, planet-torching, greed-is-good Reagan years.

“These were years spent amid the moneyed elite of Manhattan and LA and the Hamptons, in the overheated bubble of the world’s glitziest, most glamour-focused magazine publishing company, Condé Nast, during the Reagan era,” she explains in the preface. “Please don’t expect ruminations on the sociological fallout of trickle-down economics.”

(I won’t!)

Brown has a lovable side, especially when she describes her struggle to balance the needs of her baby son with her insatiable professional drive. But make no mistake, she was a pampered poodle living the extravagantly futile Lifestyle of the Rich and Famous; a magnet for the kind of cultural power that can be bought and paid for by billionaires and luxury brands. Mainly, she was an entertainer. But Brown’s coziness with power weakened her as a journalist, and paved the way for today’s near-total corporate capture of media.

Page after page, obvious similarities to our own moment leap out—the bothsidesism, the faux-objectivity, the calls for “civility” and the benefit of the doubt invariably extended to wealth and power; the infinite distance between the editor and hoi polloi, her readers. Ad pages, fashion designers, marquee names, Hollywood, Wall Street, New York society galas, subscription numbers, fame, wealth, profit, seating charts—the glamour, clotted and cloying, globbed like a fungus over everything resembling a world you’d want to live in. A full forty years later, and so little has changed.

The roster of Brown’s gazillionaire sponsors is edifying on its own: after Si Newhouse came Barry Diller, Sidney Harman, Harvey Weinstein—men whom she could describe as “fascinating” while tugging on the leash now and then. When a reporter asked her to name a woman role model, she found herself “stumped”—“I know it’s the wrong feminist answer, but most of my role models have been men. They always had the lives I wanted.”

Media potentates were once paid a lot to provide the world’s crassest, most vicious creeps with a veneer of sophistication and charm (including Donald Trump, who in 1987 was described in Vanity Fair as “New York’s smartest real estate baron,” with an excerpt from The Art of the Deal). But is there a single modern conservative, or Republican, or Harper’s Letter signatory, even, whom the fabulosos of today’s New York would invite over to dinner? In the mid-eighties it was still possible for political conservatives to pass as “civilized,” and that may no longer be so.

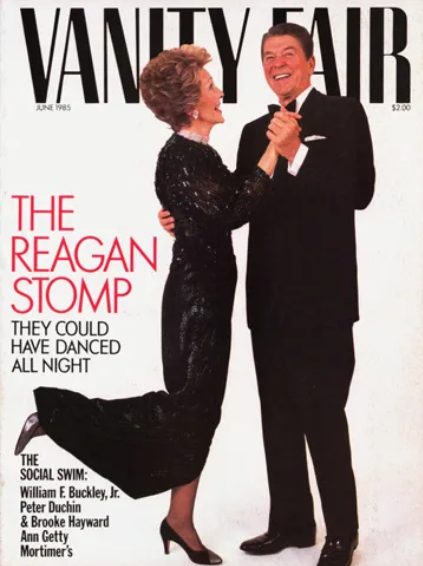

When the newly reelected Reagans were photographed by Harry Benson for the June 1985 cover of Vanity Fair, Brown had some trouble securing photo approval from the White House for the images; at one point Si Newhouse called her on the carpet to tell her, “the first lady is very concerned.”

(“Huh? Whatever happened to editorial independence?” she squeaks, describing the scene.)

“You don’t monkey with the White House,” her boss tells her (“grimly”).

That is how our intrepid editor went bravely to bat for press freedom, to provide the public with photos of Nancy Reagan “twirling around” with her husband—who, at the time, was sneakily funding Nicaraguan death squads, supporting the apartheid regime in South Africa, etc. Here is a portrait, drawn in the crudest lines, of the press we are still enabling, a psychotic system of bought-and-paid-for PR, political machinery and social horsetrading that put its allegiance to power first, and to readers way, way later.

(The text accompanying the Reagan photos in Vanity Fair, by the way, was written by the late William F. Buckley, Jr., and not by his son Chris, as Brown inexplicably reports in the book. It’s excruciating, even for Buckley Sr. He likens the Reagans—“the ruling couple”—to the old Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and compares Nancy’s face to the Pietà in St. Peter’s, and there’s also “the brummagem nature of it all” and “cockney billingsgate,” and I don’t even know. Elsewhere, Brown makes a freakish reference to Bill Buckley’s “pale, sexy, contact-lens stare,” an image that will haunt me until death’s merciful release.)

Rereading these old magazines is fantastically surreal now, a portrait of the world and everything in it as pure spectacle. Lloyd Grove’s July 1986 profile of Rosario Murillo, for example, can’t begin to anticipate the coming horrorshow of Nicaraguan politics, nor the fact that 2023 will find Murillo still First Lady of Nicaragua—and barred from entering the US, along with her husband, the erstwhile radical leftist turned capitalist and now openly autocratic President Daniel Ortega. But back then, Grove could blithely describe Murillo’s “lithe body,” and “the cherried lips of a fortune-teller.” He caught up with her at a PEN do, where she was clad in silk brocade and shooting the breeze with Norman Mailer, who told her, “The secret fear of every capitalist is: What if God is a Communist?”

Delicately superior, Brown found the model Jerry Hall “off-puttingly trashy,” but later warmed to her, in the company of Mick Jagger, at Malcolm Forbes’s birthday party. Reading this, knowing that Hall will eventually marry and divorce Rupert Murdoch, produces a peculiar kind of sadness, at the depiction of a world with no humanity or meaning beyond wealth and the trash it can buy.

“The desire to raise my intellectual sights is like a thirst,” Brown says, but no, because she had the hugest opportunity and blew it—the chance to write about, oh, I don’t know, the sociological fallout of trickle-down economics—in favor of things like a chapter called “Ten Thousand Nights in a Cocktail Dress,” her house in the Hamptons and her apartment in Sutton Place, and the whole bald transactionalism of her unshakeable loyalty to power and prestige in a pretty, blonde, civilized-looking, Milton-quoting package.

The means by which journalism is funded will always determine its ultimate integrity. Where the money comes from and why controls what we can read, and what we can understand. I can’t blame one social-climbing British wackadoodle for those ever-narrowing windows of information and insight, but there can be no question that her techniques are alive and well.