Barbara Doyle opened her restaurant at 5am every day. For ten hours she’d cook for regulars living and working in Belfast, Maine, a small harbor town two hours up the serrated coast from Portland. She’d close the restaurant mid-afternoon, then open the attached cocktail lounge later in the evening.

On a March afternoon in 1981, Doyle had an uncommon visitor. As she cleaned her restaurant and prepped food for the next day’s service a lanky man with floppy hair and searching eyes walked in and introduced himself.

“I’d like to play for you,” Jonathan Richman said.

“Oh?” Doyle asked. She had no idea who he was.

Even today, Richman’s name isn’t familiar to everyone. To casual music listeners, he might be best known for his quirky ‘90s appearances on Late Night With Conan O’Brien (where he was the second-ever musical guest, after Radiohead). Others may recognize him as the guitar-toting troubadour in the film There’s Something About Mary. Yet many, like Doyle, have never heard of him at all.

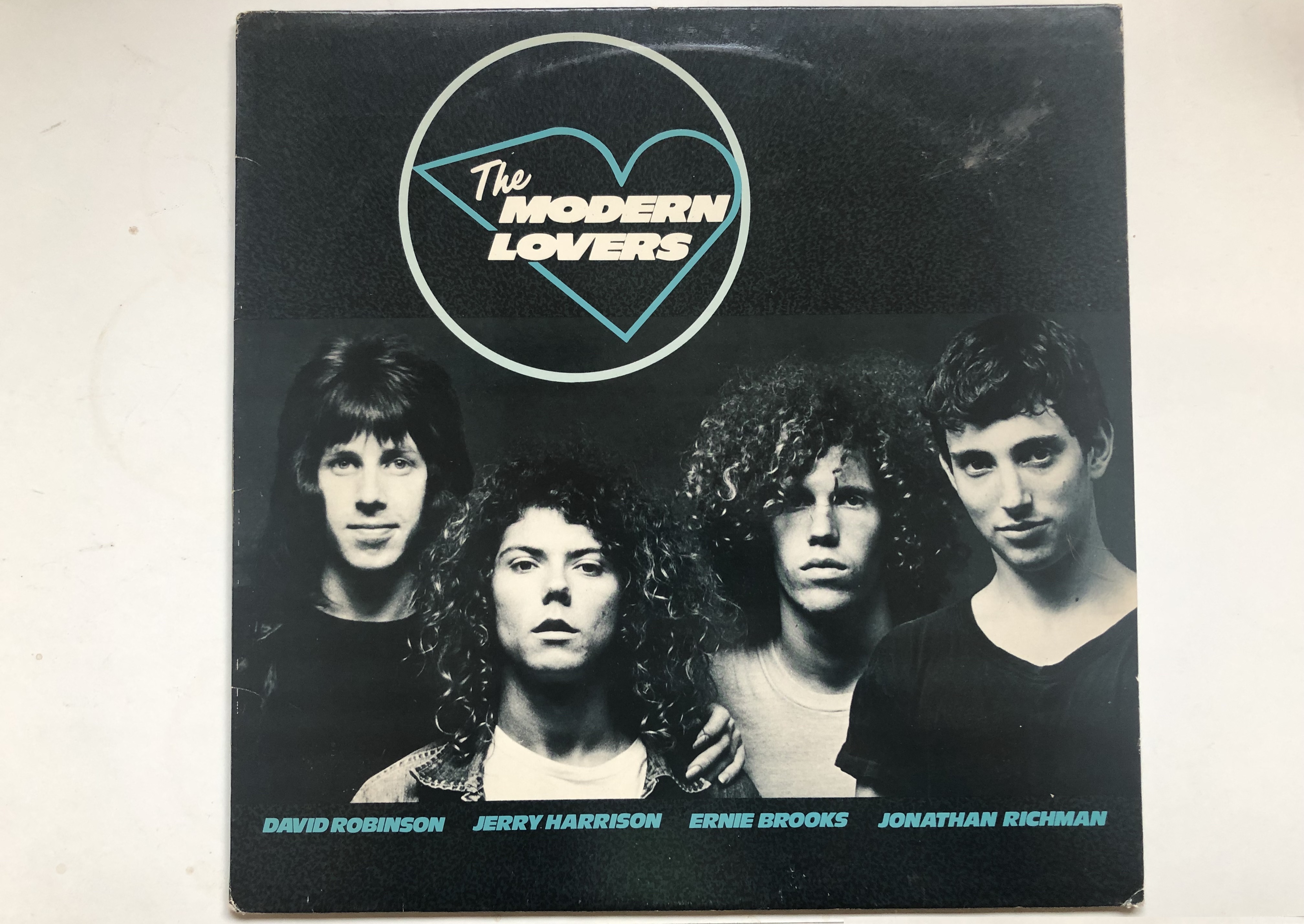

But as Scott Cohen wrote in Spin magazine in 1986, Richman’s band The Modern Lovers “were legends before anyone had heard of them.” They are the bridge between the late-Sixties fuzzed-out art-rock of the Velvet Underground and the stripped-down punk rock aesthetic that came a decade later. In Cohen’s words, “They were a new-wave band long before punk was a musical term.”

That afternoon, though, Doyle only had one question.

“How much would you charge me?” she asked Richman.

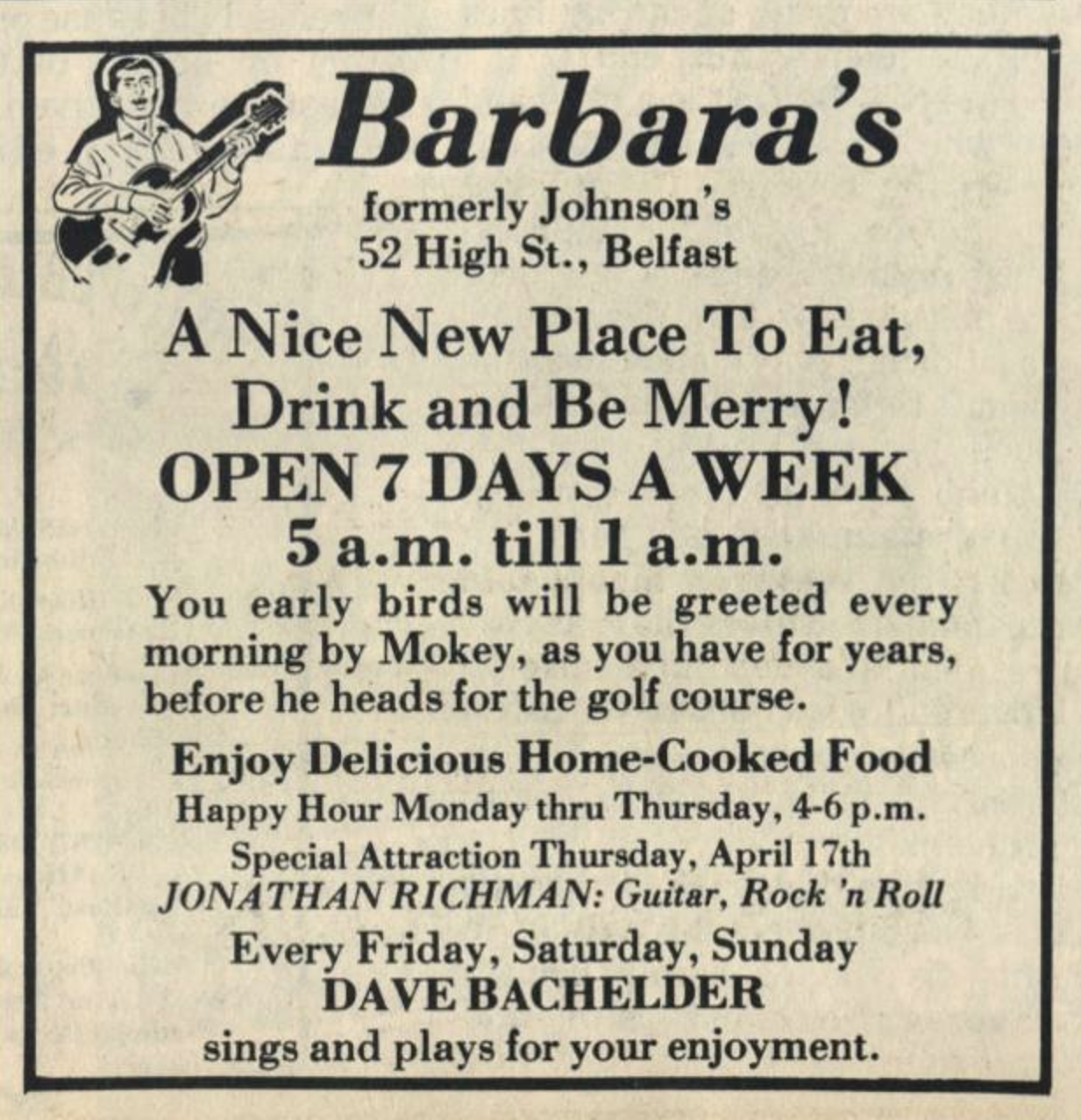

Without hearing him sing or play, she booked him to perform in her newly opened bar. She then took out an advertisement in the town’s weekly newspaper:

Special Attraction, Thursday, April 17: JONATHAN RICHMAN, Guitar, Rock ’n Roll.

At age 16, Jonathan Richman published the essay “New York Art and the Velvet Underground” in the Boston fanzine Vibrations. He’d been a fan ever since a friend brought the band’s first album, 1967’s The Velvet Underground and Nico, over to his suburban Boston home. Recounting the experience on Radio Valencia in 2014, he said: “When I first heard the opening parts of the song ‘Heroin,’ I went, ‘These people would understand me.’” Richman did not drink or do drugs, but something about the music resonated with him. He started going to their shows at the historic Boston Tea Party. The underage Richman designed show posters and traded them for access into the club.

“I’d say, ‘Here’s a poster I made. Can I get in free?’” he said.

Then, in the early spring of 1967, as Richman walked through Harvard Square he spotted a man wearing a brown corduroy sport coat, carrying a guitar case.

“Excuse me, are you Lou Reed?” he asked.

Richman confessed his love for their first record and the Velvet’s unique brand of percussive dissonance.

“Really?” Reed said.

“Yeah, for example, the way you use the guitars like they were drums,” Richman told him.

“Wait a minute, are you saying using the guitars, the rhythm guitar tracks, as percussion instruments?” a surprised Reed asked. Richman said that, yes, that was exactly what he was talking about.

Reed replied: “That’s what we do! And you heard that?”

From that point on Richman became the band’s self-professed mascot. “They knew I had to be there,” he said. “They knew, as obnoxious as I was, that it was life and death. They knew.” He saw the Velvets perform dozens of times in Boston before he moved to Manhattan in 1969—crashing, for a time, on their manager Steve Sesnick’s couch—to be even closer to the band.

Backstage before shows, the Velvets’ lead guitarist Sterling Morrison would give Richman impromptu lessons. Morrison taught him how to play more than the rudimentary chords he was accustomed to banging out on his $10 guitar, a leftover bingo prize his traveling salesman father had given him. Before he left Boston, Richman had performed free Sunday shows in Cambridge Commons. But in New York City he graduated to (an infamous) performance on the rooftop of the Hotel Albert in Greenwich Village, and then to actually opening for the Velvet Underground when the scheduled band didn’t show for a gig in western Massachusetts. He borrowed Reed’s Gibson Stereo guitar and played for 20 minutes. He remembered singing early versions of later hits “Roadrunner” and “Girlfriend.” Afterward his tutor, Morrison, said, “Well, Jonathan, that was quite remarkable.”

Richman returned to Boston in 1971 and formed The Modern Lovers. The band opened for other up-and-coming Boston acts like Aerosmith and The J. Geils Band. Famed music critic Lillian Roxon caught one performance, which she wrote up on March 20, 1972 in the New York Sunday News:

Their music is a kind of mixture of Velvet Underground, Kinks, and the late Buddy Holly. Listening to 19-year-old Jonathan Richman sing “Roadrunner” is as exciting as listening to the early Velvets. Powerful, danceable, sinister and funny all at the same time.

Soon after the review appeared, record companies from Columbia, A&M, Warner Bros., and David Geffen’s Asylum began a bidding war. Clive Davis, then head of Columbia Records, famously came to see the band in a gymnasium in North Cambridge.

Eventually, Richman and company signed with Warner Bros. and decamped to California, staying at Emmylou Harris’s house in Van Nuys. They’d arranged to record demos with John Cale, a founding member of the Velvet Underground, and cut eight tracks in Los Angeles. But Richman had grown increasingly uninterested in the band’s amplified garage-rock sound, refusing to play “Roadrunner” at shows. Frustrated, Warner Bros. dropped the band and shelved their record. The Modern Lovers broke up. Keyboardist Jerry Harrison joined The Talking Heads, while David Robinson helped form a new band called The Cars.

Jonathan Richman set out on his own. Wanting to pursue a quieter sound, he played retirement homes and day care centers. His songs were wide-eyed wonders that blended folk, rockabilly, and doo-wop. His voice, the sound of smiling. In spite of his unimpeachable proto-punk credentials, Richman had always shown a rare innocence.

In 1976, with new bandmates, the independent label Beserkley Records released an album of new songs called Jonathan Richman and The Modern Lovers. Label founder Matthew Kaufman approached Richman about also releasing the original demos from the 1972 recording session. Richman was reluctant.

“I said, ‘I guess if you want to. I’m not thrilled with the idea because I didn’t even consider it my first record,’” Richman recounted to an interviewer on his October 2003 concert DVD Take Me to the Plaza. “To me it was just a bunch of demo tapes. But I said, ‘Oh okay.’ And so he released all those things which to me was just old history.”

So it was that The Modern Lovers reached an audience, years after the band had already broken up. The album would become canonical, but Richman was already moving in a different direction. As Marc Hogan has recounted in Pitchfork:

Just as the Modern Lovers’ belated popularity was cresting on the punk wave, Richman formed a new version of the group and pushed it in a different direction, with prominent acoustic guitar and what seemed like songs for children.

Songs like “Abominable Snowman in the Market,” “Rockin’ Rockin’ Leprechauns,” and “Here Come the Martian Martians” confounded critics. Reviewing their 1977 record Rock ‘n’ Roll With the Modern Lovers in the Village Voice, Greil Marcus issued Richman a warning about following his muse too far: “Jonathan might find himself deserted by the fairy-tale audience that lives in his head, the audience to which his songs are ultimately addressed.”

Yet Marcus called the record one of his favorites of that year.

“By 1978, Richman and these Modern Lovers had parted ways, too,” Hogan wrote. “And here’s where some accounts of Richman’s decades-long career lose the thread.”

What happened?

Jonathan Richman moved to Maine.

In a 1993 interview with Tom Hibbert for Q Magazine, Richman said: “Boston’s got a kind of sad beauty to it. You know what it reminds me of? Belfast.”

He’s referring to Belfast, Ireland. But in 1980, while living near Belfast, Maine, Richman told the fanzine Boston Groupie News: “There’s something haunting in beautiful sadness.” That statement strikes me as quintessentially Maine, a state whose geographic beauty masks a stolid sorrow.

I wanted to ask Richman about that quote and about living in Maine. But, he famously doesn’t do interviews. Sort of. As far back as 1977, Ian Birch noted in Melody Maker that Richman “will never give interviews, though he does occasionally mail brief replies to written questions.”

Richman’s interview anxiety is evident in Take Me to the Plaza:

Everybody gets misquoted in this business. I get misquoted where, some of it gets repeated and I hear it over and over again. First, if you read it in print that I said it, there’s a 50 percent chance that I never said it. I think that’s probably true of most guys and girls in the business.

He then went on to list publications that had misquoted him.

Nonetheless, I emailed Debbie Gulyas, the publicist at Richman’s label Blue Arrow Records in Cleveland, to see if it was possible to arrange some sort of communication. She quickly wrote back and outlined parameters that I was familiar with from reading other Q&As online:

Hi Josh,

You may email your questions to me and I will FAX them over to Jonathan since he does not communicate via the internet. Just so you are aware, Jonathan will want the questions/answers published exactly as written and presented without any paraphrasing or commentary on his answers. He chooses to work this way so that he is not misquoted.

So I sent my Maine questions to Gulyas, who then faxed them to Richman. He was preparing for a short tour of California, where he now lives, but said he would respond once it was over.

In November of 1971, Mother Earth News published its twelfth issue. Inside was an advertisement—“Hardy Homesteader Needed”—printed in the Contact section. The letter explained:

A hardy homesteader is needed to develop 37 acres of partly cleared land in central Maine into a producing organic farm. This is a beautiful site with 2/3 mile frontage on a large but unpopulated river…the nearest neighbor is about a mile away and a rocky dirt road is the only improvement.

The letter also included a deliberate reference to Helen and Scott Nearing, the couple who famously branded homesteading in Maine as “the good life.” Mike Hurley responded, and the following spring he moved from Boston to Clinton, Maine with his brother Peter, soon-to-be first wife Kathleen, and their two dogs Coco and King.

They lasted one winter.

“It was bleak, but…it didn’t really feel that bleak. We had signed up for it,” Hurley said. “It’s really in retrospect that you realize how tough the times were. At the time, people in their right mind wouldn’t have moved there. But we weren’t in our right mind. We were homesteaders.”

Hurley returned to Maine in 1976, and two years later settled in Belfast, a town of 5,000 people in the state’s midcoast. Belfast sits on the mouth of the Passagassawakeag River, which empties into the Penobscot Bay. The Nearings lived across the bay, in Cape Rosier.

A year after moving to town, Hurley opened the Belfast Café at the corner of Main and High Streets. At the time, locals referred to Hurley’s place as a “fern bar.”

“What Belfast and most of Maine had were very rough-and-tumble working bars, and this was not,” Hurley remembered. “This was a folk musician’s bar, with food that you would recognize today as being completely normal, but back then it was sort of avant-garde. ‘My God, they have a turkey-bacon melt? What is that? They put tomatoes and lettuce on sandwiches!’ That’s what it was like back then.”

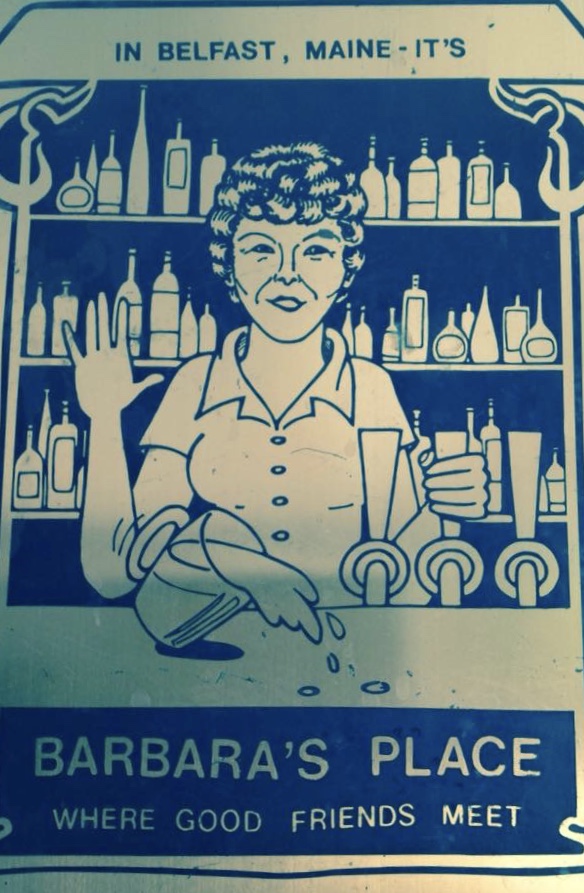

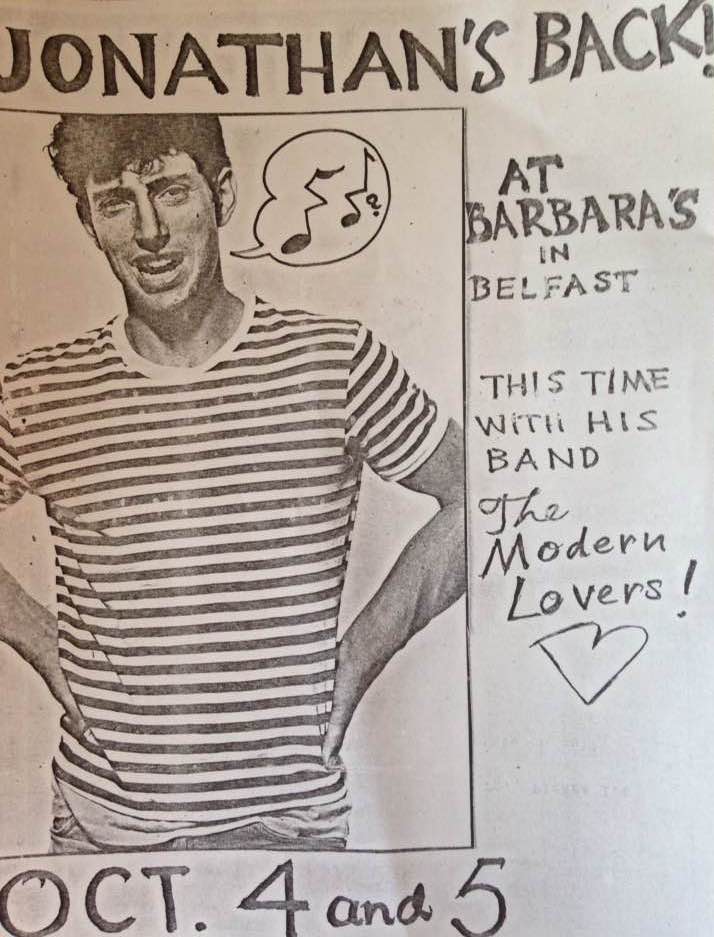

Eight months later, Barbara’s Place opened at 52 High St., a few dozen paces east of the Belfast Café. The two bars would be part of Belfast’s cultural transformation during the 1980s, each hosting the same local musician.

Hurley booked musical acts for Friday and Saturday nights, and a couple years after he opened, a shy man, whom he initially thought was “a little bit odd,” walked in.

“I’m interested in playing here,” Hurley, 67, recalled Jonathan Richman saying to him. “And I said, ‘Sure, what kind of music do you do?’

“And he goes, ‘Oh, I don’t know, kind of by myself guitar rock and roll. My own songs,’” Hurley said. “Then he said, ‘You want me to play you a few songs?’ And I go, ‘Sure.’”

The Belfast Café only seated 45 people. On that night regular customer Richard Norton stood with his back to the stage, drinking his beer at the tri-cornered bar that Hurley built. Hurley remembered Norton as “a real music hound.” The stage, a short platform only 10 inches higher than the main floor, was tucked behind Norton into the back-left corner of the room.

“Jonathan is getting out his guitar and he starts playing, and you can see Richard’s head kind of snap,” Hurley said. “And he goes, ‘Mike! That’s Jonathan Richman!’ And I’m like, ‘Uh, yeah, who’s that?’”

Richman lived, for a time, in the small town of Appleton, Maine. To call Appleton a “town” is to stretch the credulity of that word. Today, a little more than 1,300 people are spread out over 33 square miles. A neighborhood consists of any assembly of two or more houses. There is no downtown. A drive along Gurneytown Road puts one in contact with chickens and ducks and cows and a baby mule—the type of animals listeners encounter in Richman’s song “Party in the Woods Tonight” on his 1979 album Back in Your Life.

The drive north from Appleton to Belfast arcs across Route 131. The trip is unremarkable; a thin, two-lane road glossed on both sides by tall pines and old-growth birch. The 25-minute trek induces hypnotic, tunnel vision. Richman would sometimes stop into Barbara’s Place after the restaurant closed, but before the cocktail lounge opened, and the two would sit and chat.

“In fact, one time I took a pie out of the oven,” Doyle remembered. “And he said, ‘You just make that?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, you wanna piece?’”

It was during these off-hours chats that Doyle and Richman struck up a friendship that has lasted 40 years.

Despite a population boom of 13.2 percent throughout Waldo County in the 1970s, the number of people living in Belfast, its county seat, increased by only 286. During the next 10 years, however, many of those homesteaders traded their topsoil for town.

“We were all discovering, ‘Oh my god, I have to make a living,’” Hurley said. “Or, ‘Oh, my kid needs healthcare.’”

Not that Belfast was an economic salvation. At the time, almost two dozen businesses on Main Street were boarded up. The town’s main employers were a seasonal sardine plant, a shoe factory, and two chicken plants.

“I remember a chicken dropping out of the truck right outside my restaurant,” Doyle said. “I was just opening up, and a kid was out there grabbing it to take home.”

The Maplewood and Penobscot Poultry processing plants were located just above Belfast Harbor. Together, they butchered nearly one million chickens per week, and the town became known as “The Broiler Capital of the World.” With little regulation, much of the waste from these plants was discharged into the bay. Over time, a skein of chicken fat covered the water, earning the town a more dubious nickname: “Schmaltzport.”

The Maplewood Plant closed in 1980, and the Penobscot followed suit in 1988.

“These are all bottom-wage industries, week-to-week,” Hurley said. “And then they’re failing! So, we were poor to begin with, then they went bust.”

One result of that economic precarity was entrepreneurship.

“If you could find work it was really low pay,” Hurley said. “That’s why so many people started their own business.” Barbara Doyle was one of them. She took over her father’s restaurant—Johnson’s Lunch—in 1972, and then expanded.

“In 1980 I bought what was the old Dutch Chevrolet Building, which was across the street,” she said. “And I started a restaurant, and I started a cocktail lounge and then a taxi business. I had eight taxis there.”

Doyle created a brand, printing everything from t-shirts to pencils with her advertising slogan: “In Belfast it’s Barbara’s Place: Where Good Friends Meet.” Those good friends, however, could be insular. Maine is not an overly welcoming place. The native term for residents not born in-state is “from away.” Megan Pinette, now the curator of the Belfast Museum and president of the Belfast Historical Society, moved to Belfast with her husband Dennis in 1984. She remembered the locals being accepting, if not outwardly friendly.

“There was always a skepticism,” she said. “The question we got asked the most was: ‘Are you going to live here year-round? Or are you going to go away for the winter?’”

Despite the native standoffishness, there wasn’t a significant clash of cultures when the homesteaders moved to town. “Neither one of us was a threat to the other,” said local historian Jay Davis. “We weren’t going to take people’s jobs, and we didn’t feel they were going to lower our property values or anything.”

Davis himself had moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Monroe, Maine in 1971. He was disaffected by the failure of the anti-war movement to slow U.S. involvement in Vietnam, so he bought a 130-acre farm for $21,000. “I thought maybe we could come to Maine and become self-sufficient,” he said. “And try to start another movement.” He became editor of the weekly Republican Journal in 1980 and moved to Belfast a year later.

Slowly a new cultural ecosystem began to develop in Belfast. “You come here and you’ve got artists and young people, and people who have also bought old houses,” said Pinette.

Eventually, contemporary art galleries opened on Main St. “It was not lighthouses, sea gulls, and crashing waves,” Pinette said. “It was a little more conceptual.” After showings, folks would gather at the Belfast Café, then head to Barbara’s later for dancing.

“I used to just love going to Barbara’s. She’s such a character,” Davis said. “She said to me one time: ‘I can dance you under the table!’ And I said, ‘Oh, bullshit! Let’s go!’ She was great.”

Belfast’s transformation seemed to happen slowly, and then all at once. As Davis wrote in his 561-page History of Belfast in the 20th Century, co-authored with Tim Hughes:

A critical mass of artistic and creative people arrived. Other professional people were attracted, seeing in Belfast a rough, uncut diamond, with its functioning brick downtown, it’s working waterfront, and its abundance of well-preserved 19th century architecture, all overlaid by a grimy layer of chicken fat, shoe leather and elbow grease.

The natives and newcomers represented the old and modern worlds, and that push-pull tension gave Belfast a vibrancy that its residents felt was honest. “I didn’t see it as the pits. Belfast was real,” Davis quoted one resident as saying at a public meeting in 1998. “That’s why I didn’t go over to Camden. I wanted to just go someplace that was genuine, that was authentic.”

Both bars sat a quarter-mile up the hill from the chicken plants. It would take workers five minutes to make their way up the 133-foot incline from the harbor. The poultry workers preferred Barbara’s, while the homesteaders and hippies went to the more rococo Belfast Café.

“Barbara’s Place was definitely rough-and-tumble,” Hurley recalled. “I saw some amazing fights out here. You wouldn’t be attacked, but if you were looking for a fight, you could be accommodated.”

Davis remembered police officers gathering in a staging area across the street from Barbara’s. “Every Friday night, every cop in Waldo, state police, sheriff, Belfast police all went to that parking lot where there would just be endless fights,” he said. “They’d break ‘em up. ‘Go home! Get out of here!’ It was famous. Friday Night Fights in Belfast.”

But Doyle, who was born and raised in Belfast, saw her clientele differently. She had known the poultry and sardine workers all her life. “They were the common people,” she said. “The people of Belfast.”

Doyle was so fond of her customers that she invited many of the regulars to her wedding in late December 1981, which was held in her cocktail lounge. When she told Rick Doyle, the 23-year-old son of her fiancé Russell, that Jonathan Richman was going to perform at their wedding, Rick was skeptical.

“Not that Jonathan Richman?” he asked.

Despite their after-work chats and his performances at her bar, Doyle still didn’t know just how famous Richman was. When Rick questioned her, Barbara demurred, so he retreated to his boyhood bedroom in Orland, Maine and dug through a stack of magazines. He returned a few minutes later and confronted his dad and Barbara.

“Jonathan Richman is in my Rolling Stone!” he said.

“Oh no, it’s not that one,” Barbara remembered telling Rick. “Then the day of our wedding, he came over and said, that is Jonathan Richman. And I had no idea.”

For a wedding present, Richman painted the couple a landscape, which Doyle hung in her bar. The painting now rests on the wall of their winter home outside Port Charlotte, Florida. On the frame Richman wrote:

Dear Barbara: When I first met you, I knew you were young inside and that you were full of life. I got the feeling that you were just beginning as a person, that your life was just beginning. In other words, it was still springtime. So I’m glad to see you starting something new today, something like springtime, something that could make you get younger every year. I hope it does, and I know that I’ll know you for many years. Good luck to you and Russ. Your friend, Jonathan.

And on June 19, 1982, when Richman wed his first wife, Gail Clook, back in Appleton, Barb and Russ were in attendance. They watched Richman once again perform for everyone. “Sang all the way through it!” Doyle said. “I wasn’t sure he was married!”

The tenderness in Richman’s painting inscription was evident in his writing from the start. In 1973, Creem magazine ran a story mocking Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons for a lack of machismo. Annoyed, Richman mailed off a brief letter to the editor titled, “Masculine Arrogance Blows.” In two paragraphs he defended the group, and advocated for an unironic point of view that another American writer would later term “single entendre principles.” Richman concluded: “And by the way, what’s wrong with a man singing ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’? Can’t a man want to be friends for a long time instead of just for a night, too? Can’t you look at that song as at least partly meaning that?”

Often, however, critics mistook Richman’s vulnerability for naivete. They saddled his songs with the adjective “childlike.” Richman pushed back against that designation in a 1980 Q&A with Boston Groupie News: “My songs are written for everyone. Let’s put it this way: my songs aren’t just written for adults like other rock ‘n’ roll. I do like to include children.” Two decades later, Richman told his Take Me To the Plaza interviewer that he stopped playing the so-called children’s songs because people misinterpreted his intent. “It was actually supposed to move people,” he said. “It wasn’t supposed to be all cute.”

Some critics understood Richman’s approach. He wasn’t childlike; he was an empath, someone who could apprehend the emotional state of another person and bear their psychic weight. Lester Bangs saw that early on, writing: “only one in 20,000 has the nervy genius of Iggy or Jonathan and is willing to sing about his adolescent hangups in a manner so painfully honest as to embarrass the piss out of half the audience.”

Richman packed all those emotions into “Roadrunner” — the first track on that first Modern Lovers record. With its famous 1-2-3-4-5-6 count-off and Velvets-inspired two chord progression, “Roadrunner” remains Richman’s most famous song. A paean to suburban Massachusetts, he sings about driving along Route 128, late at night, as antidote to loneliness. Local landmarks like the Stop N Shop, the Mass turnpike, and the neon glinting off the factories and auto signs offer consoling comfort, as does the endless refrain: “radio on!”

The filmmaker Richard Linklater has called “Roadrunner” the first punk song. Johnny Rotten, the snotty Sex Pistols singer, once famously proclaimed it was the only song in the world that he didn’t hate. Twice in the last five years the Massachusetts House of Representatives tried to make “Roadrunner” the official rock song of the Commonwealth. Not everyone, however, was enamored with the idea. A 2013 bill proposing the legislation was countered with a rival bill advocating for Aerosmith’s “Dream On.”

The career trajectories of Richman and Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler are wildly divergent, but Tyler remembered watching Richman perform long before either of them were debated on Beacon Hill. In a 1997 interview with the Boston Phoenix, he said: “I mean, I fucking sat in 1969 in a coffeehouse in Cambridge and watched this guy and I remember looking at Joe Perry and saying, ‘This guy’s out of his fucking mind, what the hell is he doing?’ Because he’d go on for 20 minutes singing ‘And the radio’s on!’”

While “Roadrunner” remains the most well-known song on that first album, music writers often point to two other tracks as emblematic of the duality of Richman’s worldview. His song “Old World” is a tribute to the spirit that delivered him, with lyrics like: “But I still love my parents / And I still love the old world.” But the album closes with “Modern World,” a steadfast challenge to nostalgia. His ability to move along this astral plane made an impression on critics. Writing for New West in 1979, Greil Marcus said: “Like no one else currently making records, Jonathan Richman can write and perform in something like the style of a very old kind of rock ‘n’ roll, and yet never sound nostalgic, revivalist or even revisionist: He just sounds right, complete—accurate.”

But Mike Hurley couldn’t remember ever hearing “Roadrunner” at the Belfast Café. Likewise, Barbara Doyle could only recall one song of Richman’s, “I’m a Little Dinosaur.” A favorite at both bars, as well as at Doyle’s wedding reception, the song does not appear on any of Richman’s studio recordings.

The two-minute clap-along is a perfect example of a song that appears “childlike,” but actually bears significant weight. Singing in the first person, Richman becomes the nominal “little dinosaur” who is “real old, don’t you know? / born 10 billion years ago.” However, he feels like an outcast and decides to leave: “But they don’t love me here enough and so / I’m planning to go away.” Both children and the flies that used to buzz around their prehistoric friend realize they miss the little dinosaur, whom they never fully appreciated when he was around. They repeat the searching chorus: “Where’s the little dinosaur? / Where’s the little dinosaur? / Where’s the little dinosaur? / He must have gone away.”

When Richman performed this song, he’d set down his guitar, drop to all fours, and pantomime the reptile’s departure, often wiggling his butt as he crawled away from the audience. On cue, the next verse has the children lamenting the dinosaur’s exile, singing “Oh no, please don’t do / Oh no, please don’t go / Don’t go little dinosaur / Please don’t go away.” At this beseeching, Richman turns tail and returns to the modern world—“Okay, I’ll come back / You know I’m back to stay”—much to the delight of the audience.

The idea of performing “I’m a Little Dinosaur” at Barbara’s Place still impresses Hurley.

“You know, it wasn’t a big stretch for him to play in my bar because, if you started a fight in my bar we didn’t buy you a beer; we threw you out,” Hurley said. “But in Barbara’s Place…You had to have some real cojones to walk into that place and stand on the stage and do ‘I’m a Little Dinosaur.’ And he did it.”

And what did the chicken workers at Barb’s think?

“Oh, they loved him,” Doyle said.

At the end of summer, I received an email from Blue Arrow Records. It contained a PDF of a fax from Jonathan Richman, called “JOSH Q&A,” with his answers to my questions.

- In “New England,” you sing “I’ve seen old Israel’s arid plain. / It’s magnificent, but so’s Maine.” What was it about Maine that you found magnificent?

Night sky, the woods, coastline…the small town center when its 10 degrees.

- You wrote “New England” before you lived here. When and where did you first visit? What were your first impressions?

Born in Boston; grew up in Natick, Mass.

- You played “Up in Cold Maine Under the Stars” in Amsterdam in 1978 and in Apeldoorn, Holland in 1979, but seemingly nowhere else, and it doesn’t appear to be recorded anywhere. How does that song go and what inspired it?

I forget how it went and have long forgotten what the Dutch audiences thought.

- I’ve talked with the owners of bars you played at in Belfast, Maine. Both Mike Hurley of the Belfast Café and Barbara Doyle of Barb’s Place, whom I know you’re still friends with, immediately named “I’m a Little Dinosaur” as your most popular song. How do you remember the crowd’s response to it at the time?

I thought people liked most of the stuff I did for ‘em. I don’t remember any one song standing out.

ANSWER TO ALL OF THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS IN THE PARAGRAPHS BELOW:

- In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Belfast was beset by poverty. The town had two divergent communities: a hardscrabble working class employed mainly by the chicken processing plants and sardine factory and a growing number of back-to-the-land hippie agricultural and artist-types. Each tended to congregate at their own bar, Barb’s for the plant works and the Belfast Café for the back-to-the-landers. What was the difference playing at the two places (which, as you’ll recall, were only a couple dozen paces apart)?

- How did Belfast (and Appleton) strike you at the time?

- Both Barb and Mike described you and your shows with so much affection. What do you remember about them?

- In a 1980 interview with the punk zine Boston Groupie News you said, “Sadness, to me, when it’s beautiful leads to happiness. Sometimes I feel both at the same time. There’s something haunting in beautiful sadness.” Having lived in Maine for the past four years, that struck me as a very “Maine” statement, especially the last sentence. Did you ever feel that the state had a sort of beautiful sadness?

- Your first album after living in Maine was Jonathan Sings! How did your time here influence those songs?

- How did living in Maine affect the way you wrote, recorded, and performed music?

Barb was one of my favorites of all the people I met when I lived in Maine. Real sincere, you could tell right away, really good natured and a fabulous cook! One of the reason people went to Barb’s Place was the food was delicious!

Mike was nice to me too over at the Belfast Café. He had a good sense of humor too. The younger crowd hung out there, I recall, more than to Barb’s Place. The Belfast Café’ public seemed maybe more comfortable with material they hadn’t heard before than the public at Barb’s.

What I loved about Belfast was that it was so slow moving and straightforward compared to my home, the more quick and nervous metropolitan Boston area. Belfast on a ten degree day would be silent and rough. But also social! People had time to chat. It was, in that way, more like the way I was at eight years old: when everybody (good or bad) had time for ya.

The cold silence of Maine changed my music, sure: imparted more stillness to it, probably slowed the cadence of syllables some, too.

After the Maplewood poultry plant closed in 1980—laying off more than 1,000 workers—the city council convened a meeting at the high school gym to determine the town’s top priorities moving forward. “And the consensus was we wanted to clean up the town,” Jay Davis said. “And the second part of the consensus was we wanted to do something with the water.”

The city received a federal grant to build a breakwater in the harbor and revitalize Main Street with new sidewalks, street lamps, and trees. By the time the Penobscot plant closed in 1988, Davis said, “a direction had already been established.”

“It’s a Belfast that no longer smells,” Pinette said of that transformation. “There’s no longer chickens on the streets.”

Today Belfast is one of Maine’s most beloved towns, home to more than 7,000 people. In 1995, the arrival of Maryland-based credit card lender MBNA revitalized the local economy. The harbor has been cleaned up and now bustles with lobster boats, sailboats, and the occasional yacht.

Newcomers now flocking to the harbor town, many of whom are retiring Baby Boomers, face very different issues than when the homesteaders showed up 40 years ago. The word “gentrification” made everyone I spoke with uncomfortable, but the two main problems in Belfast today are affordable housing and rising property taxes. Despite becoming its own artsy enclave, Belfast residents are adamant that its working class history not only remains, but distinguishes the town from other coastal communities.

“If you go to Bar Harbor you really feel like you’re part of the crowd,” Hurley said. “You go to Boothbay, you go to Camden—to me they feel like superficial towns.”

“Belfast is not a tourist town,” he added. “We get tourists, yes. We welcome tourists. But we’re not a tourist town. You come here in February and we’re busy. We enforce parking in the middle of February.”

Hurley sold the Belfast Café in 1983. Today the building is home to Neal Parent’s art gallery, but the bar and raised stage remain. Hurley has since embarked on a number of other small business ventures including owning the town’s movie theater. He became Belfast’s mayor in 2000 and served for eight years. In 2010 he was elected to the city council, where he still serves. He has seen Jonathan Richman perform once since he left Maine. His reaction to seeing the singer play a 300-seat night club in New York City was similar to Richard Norton’s back in the Café decades earlier.

“He had sold out six or eight shows,” Hurley said. “And I was like, ‘Ohhh, my god, Jonathan Richman!’ He was really something.”

Richman’s second act parallels Belfast’s resurgence. He left Maine shortly after getting married and released a half dozen records over the next decade. His most acclaimed solo album I, Jonathan came out in 1992. The record includes the track “Velvet Underground”—an homage to the band that changed his life. The following year, at age 42, he made his U.S. network television debut on the fourth-ever episode of Late Night With Conan O’Brien, performing “Vampire Girl.”

After that September 16, 1993 performance, the Natick native joined O’Brien (from Brookline) and fellow-guest Ed McMahon (from Lowell) for some awkward end-of-show Massachusetts banter. He performed on Conan eight more times over the next seven years. Richman also acted in the Farrelly Brothers’ 1996 film Kingpin before stealing scenes as the wandering Greek Chorus in There’s Something About Mary.

Richman has released 10 more albums since that first appearance on Late Night. His most recent record, SA, came out in October. He continues to tour with longtime drummer Tommy Larkins. The duo performed in Ellsworth, Maine in November 2017, and again in Portland in March of this year.

Since he left Maine, Richman and Doyle, now 83, have remained dedicated pen pals.

“I’m about four letters behind,” she joked.

Despite their faithful correspondence, the two have seen each other just once in the past 35 years. After running Barbara’s Place for nine years, Doyle sold the cocktail lounge in 1989, and four years later she and Russ bought a winter home in El Jobean, Florida. In February of 1997, the Doyles were at their Florida home when Barbara saw a newspaper advertisement promoting a Richman show in Sarasota, an hour up the Gulf Coast.

“So I called to see if I could get in,” she remembered. “And they said, ‘Well, it’s first come, first-served.’

“Well, he used to play for me,” Doyle told the concert promoters. “And I’m not going to drive up if I can’t get in.”

The venue relented and told Doyle to come to the show.

“We’ll make sure you get in,” they said.

Richman was shocked when the couple came into the theater. “I walked in and walked up behind him and put my arms around him,” Doyle said. “And he couldn’t believe it.”

Barbara and Russell sat at the club’s head table. Richman joined them during the opening gig and through the intermissions.

“Everybody kept wondering how we knew him,” she said.

By then, Doyle knew just how famous Richman was. But it was a familiar scene: sitting together at a table before the gig or between sets, making time for a chat.

“It didn’t change a bit because I knew him as a person, and he was just one of the greatest guys I ever met,” she said. “And we really became good friends.”

A portion of of this story appeared in the June 2018 issue of DownEast magazine.

Josh Roiland