Me

On the afternoon of Tuesday, May 15, I was kneeling in a thick bed of star-moss alongside my house in upstate New York, plucking blades of grass and feeling unreasonably optimistic. The air felt a little hot and claustrophobic for spring, but under a canopy of soaring white pine trees – a hundred years old and a hundred feet high – I barely noticed. The moss under the trees was my favorite place, and weeding it was my favorite waste of time.

For the past month, I had been alone and bitter. My boyfriend Brett was traveling for work for weeks at a time, beaming to the masses on his social media, with his twinky little colleague stuck to his side, a better-preserved Siamese Twin. Friends from New York City came up to their weekend places and I speed-drank through dinners.

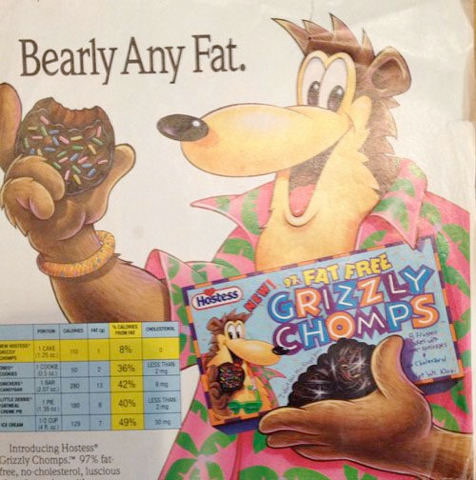

My professional flailing was particularly acute. For reasons unknown, I’d invested too much in the fate of a breezy little article I’d written for a travel website about (I am not making this up) the Museum of Failure, a cutesy traveling showcase of humiliating faceplants in the history of engineering, product development and technology: a Swedish warship so heavy it sank; LaserDisc; Tidal. My editors had accepted the piece, then “played with it” and forgotten about it, until the exhibition left the U.S., killing it for good. The Museum of Failure could now add to its collection an exhibit of me, a 50 year-old writer, agonizing over clever captions for Hostess Grizzly Chomps, for a fee of $300 that I had to bargain for and would see only after four full months of begging.

But the morning previous, I had sold a blind pitch to an editor I’d never met about a real-life vegetarian college football team in 1907. One witty email volley with him was all it took to restore my desire to reconnect with the outside world.

And reconnect I did. I made a phone-date with one friend in Tennessee for Wednesday, planned a writer’s retreat with another in Massachusetts, and left messages for my father, my sister and A.K., an old friend from college. I fell asleep that night feeling, if not fantastic, light-hearted and human. Not just willing to go on, but maybe even eager.

On Tuesday afternoon, I got the contract for the vegetarian story and instead of reading it right away and feeling swindled, as most writers do at that stage, I went outside to weed the moss and float on this mild sense of well-being just a little while longer. The sky grew suddenly dark and green, so I washed my hands in the lake and went inside, leaving the porch door open to better enjoy the coming storm. But in just a few seconds, rain was pelting the lake’s surface into a violent froth and the wind went insane. By the time I made it over to close the door, the whole lake seemed to be getting swept up into a wave. On the far shore, two huge white pine trees fell effortlessly into the water. I struggled to close the door and backed away, into the house.

I don’t remember what I did next. I may have been standing frozen or racing back and forth or huddling on the couch with my hands to my face, or maybe I performed a montage of all three. A noise like thunder boomed on every side of me, louder and louder and louder. I heard wood cracking, glass breaking. I felt the whole house being throttled and my ribcage coming undone. The windows were covered with limbs and pine needles, and everything was dark.

And twenty seconds later it stopped, and there was only soft rain. I knew what had happened. For years, during heavy storms, I had lain awake at night expecting this to happen. The only question now was how bad it had been.

On the lake side of the house, at least two giant pines had toppled over into our maple tree, across our stone dock, into the water, taking electric, phone and cable lines down with them. Another pine had split the roof of our shed and shattered the window of Brett’s studio. I scrambled upstairs where, impossibly, the ceiling appeared intact. Back downstairs, through the living room window, I saw a jungle of fallen pines crisscrossing the expanse of moss. A web of roots had yanked up our gas line from a foot underground, and the tank itself was buried in branches. When I opened the front door, I ran into the sheared-off remains of our entire front porch, pinned under yet another enormous fallen tree. Our car had been crunched to half its original height.

It is only luck that my cell phone was charged. I had one bar of service. I tried to call and text Brett, who was, ironically, test-driving a car out in the Redwoods; he didn’t answer. Then I texted Jared, who had started out as our handsome young mechanic, and now become our ideal friend. “Trees on house please come help not a joke. I am alone.” Jared, who’d been through the same storm at work just a few miles away, texted right back, further diagnosing the extent of my crisis, trying to keep me calm and away from windows, and assuring me that even though the roads were blocked, he was on his way.

Trapped, all I could do was dart from window to window, wanting it not to have happened, then facing the proof that it had. Beyond the enormity of what had changed in the physical world outside of myself, I feared what would soon change inside: the precarious dawning of hope and purpose and connection would roll backwards into despair. I thought of Brett, watching winter return for the second time in a month to kill the buds on our maple tree, and his murmuring, “I hope they come back.”

I would do more than hope. I stuffed the essentials into a bag – underwear, socks, computer, bourbon – and ventured out into the apocalypse. Out the back door, I was hit with the smell of propane. I wormed through a screen of limbs, then around the side of the house, clambered over two full tree trunks, and when I got to our road, it wasn’t a road at all, just an endless heap of fucked up trees.

Tal McThenia

Tal McTheniaTen minutes and fifty feet later, sopping wet and sticky with sap, I stopped to breathe. In the hole left behind by the twelve-foot-wide wide root ball of a fallen tree, a seasonal stream was swirling itself into a deep clear pool. I was mesmerized and euphoric. The world has been altered, I thought, and it is so fucking beautiful.

Ron

When the fallen trees became an impenetrable wall, I veered into the neighbor’s field, relishing a delirious, obstacle-free sprint up to the two-lane highway, where I thought I would probably run into Jared. But as I crested the hill, the first thing I saw was a Jeep Cherokee inside a tangle of branches and electric wires, the silhouette of an old man inside, shrieking – when I got close enough to hear – “Get me out of here! Get me the fuck out of here!”

But a half-second later, a contradictory bark: “Stop! Stop!!! Don’t get any closer!” The wires, he yelled, would electrocute me, just as they would electrocute him if he tried to get out of the car, which is what 911 had apparently told him on his cell phone, which is – I realize now – who he’d been yelling at to get him the fuck out of there.

All the guy could do was sit in there, wait for help and rant, and all I could do was stand a safe distance away and keep him company while he shouted, “I hate this fucking county! As soon as I get out of here, I’m going to move as far away from here as I can! Fuck! Sullivan! County!” And then, suddenly: “I’m Ron, by the way.”

This went on for a few minutes. As much as I felt for Ron, he was kind of a handful, and a real downer. So when flashing lights appeared down the hill, I made my escape, promising to return with help. “Is it the EMTs?” he cried after me as I rounded the bend.

It wasn’t the EMTs. It was a local road-crew truck, one of many in a long line of stopped traffic. I squealed the news of Ron to the crew. They all rolled their eyes. “I’ve already been up there to talk to him,” the supervisor groaned. “And the only thing he can do is wait until NYSEG gets here to clear those lines.” I decided if he wasn’t getting too worked up about Ron, I wouldn’t either. For the next fifteen minutes, I made idle chatter with a flag-man, who had heard that the storm was a tornado or a micro-something, that all the roads were blocked, nobody had power, and parents were flipping out because none of the school buses, which had been hauling kids home when the whatever-it-was hit, had been heard from. I was in the middle of telling him about our house, when a persistent honking finally got my attention: Ron!

Ashamed, I hurried back up the road, and when Ron spotted me through the trees and wires across his windshield, he laid on the horn, scolding me for abandoning him. When I told him it hadn’t been the EMTs after all, he shouted, “If they don’t get me out of here right now, I’m gonna open the door and get out myself!” I tried to tell him that wasn’t a good idea, considering the whole electrocution issue, but he drowned me out with more honking. I ran back down to the crew to report that the situation had now escalated. Begrudgingly, the supervisor and another crewman followed me back up to Ron.

“I told you to wait, Ron!” the supervisor groused. Ron countered with more suicidal threats and honking until the supervisor understood that a change in plans was in order. Stepping as close to the driver’s side window as he could, he looked Ron in the eye and said in a firm voice that if he wanted to get out alive, the only thing he could do was to put it in reverse and floor it.

It was a bold, dangerous plan and I was both horrified and impressed.

Ron bawled that it would never work because there were trees behind the Jeep too, at which point I chimed in to reassure him that I’d seen the trees myself and they really weren’t that big. I wasn’t so sure I was telling the truth, but I very much wanted to help the supervisor with his plan. Ron, who by now had no reason to believe a word I said, kept resisting until the supervisor raised his voice to a command: “Put it in reverse!”

Ron went silent and did as he was told.

“Now stomp it.”

Ron stomped it. The wheels spun and the Jeep went sideways, trees and live wires bouncing wildly on the roof. Terrified, Ron eased up on the gas, and both road guys began violently shoving the air with open palms, the universal sign for “Keep backing up, you dumbass.” After a lot more spinning and bouncing, and no small amount of body damage to the Jeep, Ron was free.

He leapt from the car and began circling it, which first looked like textbook shock behavior, except then I noticed he was snapping pictures of the whole scene with a disposable camera: the Jeep’s damage, the skid marks behind it, the wires and trees now lying on the pavement. There were so many things I didn’t want to know about Ron, the least of which was where he had gotten his hands on a disposable camera.

Heading back down the hill, the heretofore silent crewman smirked at the supervisor and said, “You have an excellent bedside manner.”

Jared and Gabby

The highway was still clogged with cars, trees and panicking parents, and I began to doubt if Jared would actually make it through to rescue me. So when a random stranger offered me a ride in the general direction that Jared would be coming from, I agreed without thinking.

“Sorry, this is the car I take to the dump,” she warned, opening the back door. At least three other people were crammed in back there. As we chugged up the road and they all talked around me, two things became clear: first, I had no real idea where they would be stopping or where I would be getting out, and also, my fellow passengers were the people who lived in the blue house with the huge Confederate flag. I had spent years scowling at them in their yard, and now our thighs were touching. Spotting a car that didn’t look at all like Jared’s passing in the other direction, I slapped at the window and cried: “There’s my friend! Can you pull over?!”

They wished me a bewildered good luck as I shut the door behind me. And right then, Jared’s car actually did zip by. I waved after him but he didn’t see me, so I flagged down another car.

The driver was a decent-looking middle-aged man. He gave off a cruisey vibe as soon as I got in. To comfort me for the loss of my porch, car and fragile sense of hope, he told the story of seeing a tornado flatten his entire hometown in Kansas, and then introduced himself as Ted. If the drive had been longer, things definitely could have gotten sexual.

But then, back at the road blockage where I had begun, there was Jared, work gloves on, chainsaw revved, stepping in to cut up the trees that had pinned Ron’s Jeep. The road supervisor was warning him off because of the wires, and it may have come to a chest-bumping power struggle, had I not come flailing at Jared howling his name. He set the chainsaw down and as soon as his arms were around me, I was sobbing. The supervisor turned away. Still snapping pictures, Ron didn’t even notice. Ted lingered by his car, watching our embrace, looking, I thought, as if he would like to masturbate.

I led Jared back down through the field and over the trees to check out our house. He had cigarettes. Now that I was not alone, my strange elation returned. We smoked and marveled at a dense congregation of pines, their tops all snapped at the same height. We mourned the old post office, its roof caved in under branches. And we tracked a domino-cascade – “this one fell into that one which fell into that one” – all the way to the tree that had crushed our car and porch. When Jared shook his head in horror at the wreckage, I felt proud.

On the circuitous drive back to his house, I picked off ticks and the adrenaline faded. As he swerved around limbs and live wires, I nodded off. He poured me a drink and went out to start his generator, then I tried again to call Brett and fell asleep again in a chair. When I woke up, Jared was darting around the house in a bathrobe, all wet and clean. We were going out to dinner, he announced, with his new girlfriend. He gave me detailed instructions on how to bathe in the bathroom sink, since there was no hot water, and when I emerged, the girlfriend had arrived and they were making out. I poured myself another drink.

Jared had talked Gabby up to me and Brett, but words like “chill”, “fucking funny as shit”, “grown-up” and “gets people” are no substitute for direct experience. Minutes into our ride, Gabby told me about getting pulled over for speeding a bunch of times way too close together, and how shitty it made her feel about herself, like this illusion she’d had of respectability and stability had been shattered and she was hurtling into total chaos. I knew that feeling, but had been too ashamed to spell it out to myself, much less to a total stranger sitting in the back seat.

In the half of Sullivan County that still had power, we found dinner and yammered until they kicked us out. By candlelight back at home, Jared and Gabby told stories about her three-year old son, whose gentle temperament Jared insisted was Gabby’s doing, but she, more humbly, attributed to luck. Commiserating over humiliating jobs and fraying marriages, it felt just like I was with my older sister, never mind that Gabby was twenty years younger. She had been through some shit in life, but it looked like she was going to be okay. Both of those things made me feel safe.

In the morning, after she had gone to work, Jared cooked me breakfast and I went on about how great she was. I knew that he’d told me this before, but I felt like he didn’t quite get it as fully as I did. There was no way anyone else could like Gabby as deeply as I did, not even her boyfriend.

George

To cancel all those just-made plans and phone dates, I pasted Jared’s best worst picture of the house and car into a series of tone-deaf emails and re-forgot my loved ones. Gabby had warned me that it was better to empty a powerless fridge sooner rather than later (as she’d learned the hard way during February’s blizzard), so I borrowed Jared’s boss’ wife’s Range Rover and re-entered Storm-World eagerly.

I bumped through swampy ditches and swerved around falling branches and inched under low-dangling wires. But all I could do was circle our house from a distance. There was no clear route. I drove for hours, pumped up on the thrill of chaos. The more I drove, the less I really wanted to get anywhere.

At the end of our very long road, my last possible point of ingress, I spotted our neighbor George, out for a stroll to survey the damage. George’s house looks more like an ancient barn, and it’s never been clear what basic services and amenities he has inside. He must be in his eighties; he’s tan and squat, with twinkling eyes and one or two teeth. He sported a jaunty get-up: flip-flops, baggy shorts, collared shirt under a cardigan, colorful umbrella. George has always had a tender and unguarded intimacy with me and Brett, and for a while we thought we were special, but then our other neighbor told us he’s like that with everybody.

When he heard I was heading home to deal with the fridge, he lit up. It seemed George had a refrigeration problem himself: our direct neighbors the Hulls had been letting him keep a freezer full of frozen dinners in their basement, in exchange for keeping an eye on the place while they aren’t home. A day in, George imagined, all the dinners were melting. And since he only had a crappy little hatchback that couldn’t possibly make it, could he ride down there with me, gather up the dinners and take them over to his cousin’s in Lake Huntington, where the power was back on? I tingled with delight: now my adventure had an altruistic purpose, and I had a companion.

George thrilled at the Range Rover’s power. When the route seemed blocked, he egged me on to cut through a yard. “What choice do we have?! It’ll grow back!” A bit later, he grew somber. He worried that the planet had entered a cycle of unending extreme weather, and then he said this: “The two things left in my life that I enjoy, the storm has ruined them both.”

The first thing was his “little water system” that I had never heard about before: a homemade spring/pump contraption that carried creek water to his garden and/or house. He took great pride in having invented it and savored long afternoons perfecting its operation. But now, the whole thing was buried and likely crushed under trees. And the farmers with chainsaws up the road were going to be too busy for weeks to come help. I almost volunteered Jared and his chainsaw, or maybe, even better, George and I should just drive over to Home Depot in Pennsylvania and buy a pair of chainsaws for ourselves.

What was the second thing, I asked. “My old car graveyard,” he replied and when it hit me what he was talking about, I gasped. Up the road from George’s house, on a plateau above a hillside long ago gouged out for sand-mining, was a collection of vintage autos rusting beneath a canopy of white pines. Brett and I had ridden our bikes by there hundreds of times and, while the proscenium-like arrangement of the cars had always amused us, we’d assumed it was accidental: just a junkyard above an old mine. But now, George was telling me: the arrangement was his design. He’d driven the cars into those resting places himself. And not only that, he regularly mowed and weed-whacked the grass up there, so he could more easily stroll around and “visit” his vehicles.

How could we not have known this incredible and essential fact about our neighbor? How could we not have visited the old car graveyard ourselves? How could we not have picnicked up there with George and listened to his stories of all these cars’ lives?

He wasn’t interested in my attempts at comfort, and when we finally made it to the Hulls’ house, he peered down the hill at our house, moaned cursorily at the damage and scuttled inside to gather his Hungry Mans. I took in the scene from this elevated vantage point. Our property looked like a smashed diorama. And I could now clearly see that there were no trees left to shade my star-moss, which confirmed a quiet worry I’d been squelching since the day before: the storm had ruined something very precious in my life, too.

Franklin

When Brett came home and first saw the house, he broke into jagged weeping and I held him briefly. As he wandered around and took pictures, I hung back, wondering what he was writing for captions. I felt sour, juvenile and proprietary: this was my catastrophe, not his. I couldn’t expect him to know what I was feeling – the sharpened emotional awareness, the sensory delirium, the trauma-joy – and I barely tried to explain it. I was scared he would kill it. When he left again, for Germany with the twink, I felt relief.

But two weeks into post-storm life, my senses were dulling on their own. Insurance adjusters, tree-removers and utility companies were in high demand across the region, so our house remained frozen in its wrecked state, and my moss was browning out fast. Crashing at the brand-new glassy weekend home of our friends Colin and Peter got less glamorous by the minute. On Meatloaf Movie Monday at a local restaurant, I sat alone at a table for five in a vast empty room, realizing shamefully before my salad even arrived that the original Freaky Friday would never take me where I wanted to go.

Just before my 51st birthday, my friend A.K. announced that she and her 14 year-old son Franklin were driving down from Rhode Island for a weekend college-friend get-together at someone’s farmhouse – just a few miles away, in the part of Sullivan County the storm hadn’t hit. Did I want to come over one night for dinner? I hadn’t seen some of these people in forever, and now they all had kids – multiple teenage kids. I felt like a raggedy eccentric, a nut-job failure. How would I form sentences? It took a week for me to get it together to say yes.

When I pulled up, there at the center of a porch-full of adolescents, was a boy whose body and hair had grown so much in the past year that it took me a second to accept that it was Franklin: a bean-pole with a loose dark brown ponytail running halfway down his back, a billowy t-shirt, classic Wranglers and some gorgeous old motorcycle boots that were obviously his pride and joy. He handed me a slingshot with an arrow half-loaded into it and pointed out into a field of tall grass: “How far can you shoot?”

This wasn’t the challenge I’d been preparing for. With all the kids’ eyes on me, I tucked the arrow in place between two fingers and pulled the sling back as far as I could. It would all go horribly wrong, I thought, as soon as I let go. But instead, the arrow arced high in the air and soared hundreds of yards out into the grass, almost to the road. Franklin approved. Before I could worry that the arrow was lost, little Sadie sprinted out to retrieve it, a task she’d obviously performed many times before.

Emboldened, I headed inside. Later, as I chopped cabbage, Franklin sidled up next to me with a notebook of his art, which he knew I had always enjoyed. Every page was a pencil-drawn fantasy-D&D warrior-type character that he’d dreamed up, their costumes, weaponry and special powers rendered skillfully and in elaborate detail. He narrated each page and recited each power in a deep, confident voice, politely pausing for me to bat away some adult’s admonishment that my cabbage was coming out too thick.

After dinner over a bonfire, I told the story of the storm – in too much detail and probably too loudly. The kids, stuffed on marshmallows, had returned inside to their vaping devices. But Franklin lingered, on the periphery of the light. At some point he inched closer, right up behind me, put his hands on my shoulders, and began to rub them. It was an unexpected kindness. Whether intended or not, his hands and his presence relaxed the way I was talking, and gave me comfort that I was not crazy, or at least that in my craziness, I was not alone.

“So weird the way Ron and Ted both introduced themselves so formally,” he said. I realized that no adult had caught this detail, and so from then on, I narrated only to Franklin. With each chapter, he kept asking if I’d finally been able to reach Brett. Franklin has known us since birth; to him, we are beloved boyfriends, plain and simple, inseparable halves of a single unit. It worried him that we weren’t in this disaster together.

When the adults started falling asleep on couches, I realized it was time to go. Franklin emerged from the teenagers’ lair and gave me a big, long hug. On the drive home, I saw a rangy young bear loping down the road, and wished I had Franklin’s phone number so I could tell him.

Instead, when I got back to Colin and Peter’s house, there was Brett, jet-lagged but waiting up. Nothing delights Brett more than a bear sighting, I remembered. He was the one I needed to tell. And when I did, I savored the thrill in his eyes.

Tal McThenia