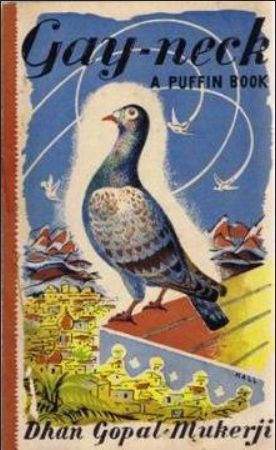

Dhan Gopal Mukerji won the Newberry Medal in 1928 for a slim children’s novel titled Gay-Neck: The Story of a Pigeon (unfortunately not a novel about a gay pigeon). It tells the story of a Chitragriva, a carrier pigeon with a colourful neck (hence the name) and his friendship with Ghond, a boy from Calcutta. Gay-Neck and his friend eventually go to war together and come back to India disillusioned with humanity. Despite being a book for children, the story illustrates the horrors of the first world war, and the Indian efforts therein. The novel’s broader message is that humans and animals have a fondness for each other that makes them kin. “Animals have young souls,” Mukerji wrote.

Gay-Neck is one among many of the books Mukerji wrote for children, all following similar patterns: They’re intended to transport children to the jungles and cities of Bengal, introducing them to talking animals and colourful trees. Based on Bengali folklore and fairytales such as Dakhinranjan Rai Majumder’s Thakurmar Jhuli, these stories were meant to introduce the very idea of a Bengali childhood to American children. These books exposed a broader world, and also provided an accurate account of India and Indian life (as opposed to e.g. the colonial works of Rudyard Kipling). In my view, Mukerji’s focus on children’s literature is far more interesting than his adult writing, because the former made Indians and Indianness real for future generations of Anglophone readers.

In the foreword to his 1917 Sandhya: Songs of Twilight, Mukerji wrote that this poetry collection was “a slender rill that has drawn its music from my Bengali which has told upon its English structure. This and many other faults of these poems are due to their unyielding adherence to spontaneity.” The ethical compulsion to contain Bengali rhythmicity, imagery, and metaphors within the structure of English poetry, explaining the disarray of the poems as a deliberate reflection of the poet’s refusal to “translate,” is a theme representative of Mukerji’s literary career.

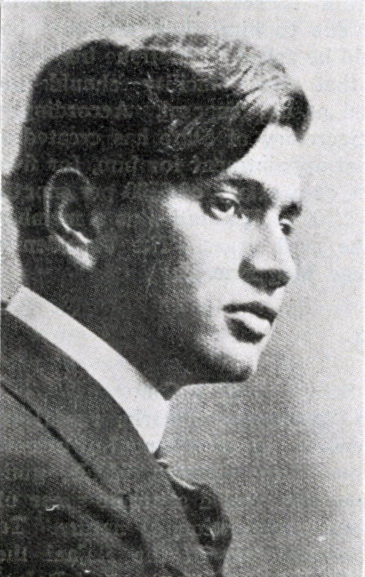

As the youngest child born to a Brahmin family in a small village outside Calcutta, Mukerji’s fate—to join the priesthood, and live a life of austerity—had already been written out for him. At the age of fourteen he was taken out of school to embark on a two-year journey as a travelling beggar, as per tradition, to learn of human nature and seek the righteous path. Thirsty for a knowledge that this religious life couldn’t provide, he renounced his priesthood and enrolled in the University of Calcutta. He spent a year in Japan and then traveled to the University of California, eventually graduating from Stanford University in 1914.

The details of his life are hazy, but we know that Mukerji’s exposure to the ideals of Marxism and the Bengal Renaissance during his time at the University of Calcutta followed him to California, where he found friends among likeminded anarchists and revolutionaries. According to his memoir, Caste and Outcast, he was immediately sympathetic to the struggles of the working class and African Americans in the US. His efforts to connect the plight of oppressed classes worldwide is evident in his friendships. With W.E.B. DuBois he wrote an editorial, ‘What is Civilization?’; he also befriended the noted Bengali Marxist M.N. Roy, who founded the Mexican Communist Party in 1917. Looking back on these friendships, we can begin to form an idea of what transnational solidarity might look like, and how it might foster dialogues once again, across borders and struggles.

By 1927 Mukerji had already made a name for himself as a writer, but that didn’t save him from being exotified by American society. In a 1927 biographical sketch written by Harriet Bond Skidmore, several orientalist tropes are woven together into an account of Mukerji’s life. “Vivid as the threads of a Cashmere shawl is the story of Dhan Gopal Mukerji’s boyhood”; “It is strange to our western minds to realize”; descriptions of his mother as a “a woman of the East”; “the jungle was his next-door neighbour”, and so forth. Predictably, too, the piece describes the deep reverence that cultured American society held for Mukerji. Skidmore closes by describing him as “a young man, vital, keenly intelligent and filled with a great love for all mankind.”

Knowing all this, however, Dhan took it upon himself to produce a different image of a ‘Man from the East’ that Americans would not expect. “There has been so much misconception about India, especially with regard to our education and social customs, that I am tempted to let the narrative go to the wall in favor of what a western friend of mine calls ‘the Oriental’s fondness for vague philosophizing.’”

Being one of the first Indian students to come to America, Mukerji took it as his responsibility to ensure that his fellow Americans would respect his fellow Indians. In his response to Katherine Mayo’s Mother India, A Son of Mother India Responds Mukerji repudidated Mayo’s attack on Indian decolonization. Mayo had cited the treatment of women and ‘backwards’ nature of the Indian religion as reasons to continue the “civilizing mission” of colonization: Mukerji unequivocally declared his support for independence. As “a son” of India, his authority to speak on Indian issues to an American audience was unassailable.

After almost twelve years of living abroad, he wrote a travel memoir of a visit to India, My Brother’s Face, comparing ‘modern’ problems facing India with those facing Americans—not to show that Indians are just like Americans or vice versa, but that, despite their vast differences, there was room for dialogue. To counter American prejudices against Hinduism, he wrote an investigative book on the Hindu thinker Ramkrishna. Mukerji was acutely aware of his position as an ‘Oriental’ in America. Descriptions such as “a mystery-detective story told by an Oriental with all the subtlety of the East” appeared frequently on the covers of his books. But instead of rejecting this category entirely, Mukerji played with the intricacies of Orientalism, and illustrated through his works that India was in certain ways not very different from America, thus redefining what it meant to be an Indian in American society altogether.

Today Bengali American writers such as Jhumpa Lahiri, Bharati Mukherjee, Dilruba Ahmed and Durga Chew-Bose have become popular in American bookstores, classrooms, and literary circles, and Dhan Gopal Mukerji—though his reputation among academics is high as ever—has practically disappeared from the popular imagination. Almost a hundred years have passed since he won the Newberry Medal; in that time Bengali American writing has become its own unstable category full of hope and anguish, constructed within the contours of a larger tradition of South Asian American identity.

Much like Dhan Gopal Mukerji, writers like Jhumpa Lahiri often deal with issues of Bengali politics, identity, or history. Trying to decide where this literary tradition ‘fits’ or what it ‘means’ raises the question: What, exactly, is the Bengali literary tradition? In our age of diasporic writing, the boundaries of literary ‘tradition’ are constantly being pushed, extended, or deconstructed entirely, all over the world. Dhan Gopal Mukerji did not define the literary landscape of Bengali America; in examining his works in comparison with Bengali writers a century later, we can see that the issue of representing an authentic Bengal to an American audience is still a vital one.

Perhaps also, the century of literary regionalism inaugurated by Mukerji shows us that the universality of human experience has always been at the heart of the Bengali literary tradition.