We decided to ride out Hurricane Ida last August in our New Orleans home. This isn’t a choice everyone gets to make: Evacuation can be stressful, expensive, and dangerous, and being in the grip of a pandemic only makes things harder.

I’m not sure my partner and I would have been any better off if we’d left, stuck in evacuation traffic on some stretch of scorched highway, aiming toward Texas with four angry cats in the backseat. Or maybe we would have headed straight north to relatives in Wisconsin, safe from the storm but a thousand miles from home. We also could have visited friends in New York, where we would have inevitably encountered the same storm we were fleeing. But in the end we stayed.

I slept little the night before, full of nervous energy. I woke before sunrise, looked at my phone, and cried. Since I last checked the forecast, the storm had rapidly intensified, spurred by abnormally warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. At this moment some questions arose: What was about to happen? Had I made a mistake? What do I do if the roof blows off?

Gearing up for a storm involves an array of activities, some of which would prove futile. We drilled in thick plastic storm shutters to cover our front window, but the wind ripped them off. We set our fridge and freezer to the coldest settings, but still had to pitch most of the contents a few days later. Our kitchen table became an ad hoc prepper station crowded with disposable batteries, first-aid supplies, non-perishable food, bottled water, flashlights, bug spray, sunscreen, motorcycle helmets, and a hatchet.

Eventually the weather got bad and the power went out, as we’d known it would. The storm was so powerful that it caused the Mississippi River to flow backward. Winds gusted at 150 miles per hour and coastal areas flooded. Throughout the region, buildings fell in and homes were destroyed, upending lives in yet another climate disaster.

We spent hours in the bathroom—the safest spot, farthest from the windows—and listened as the storm hovered over the city, rattling our old wood-framed house. There was ample time during this confinement to worry about the possibility of freak accidents, like tornadoes tearing through the neighborhood, or the large tree in our backyard crashing into our bedroom. By the end a bit of our ceiling had fallen in and we were exhausted, but all told we were OK.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

The days that followed were strange and disorienting. Large-scale destruction and the collapse of a transmission tower had wiped out the city’s electric grid. The streets were covered in debris. Some parishes outside New Orleans had suffered catastrophic damage, according to our battery-powered radio, and would have to be rebuilt. Gasoline was in short supply, and hospitals filled with COVID patients were running low on oxygen. The mayor, the police chief, and the media went on about looting, but that was bullshit. With no clear idea of when the power would be back on, many who hadn’t left before the storm decided to leave afterward. The city felt roughed up and emptied out, its precarity writ large.

Local officials lost no time in putting anti-looting measures into place, but waited days before checking on some of the city’s most vulnerable residents. Nearly a million people went without electricity for a week or more; at least ten elderly residents died in the heatwave that came on the heels of the storm. That these tragedies had been preventable made them even more appalling. More than 800 seniors were evacuated to a former pesticide plant converted into a makeshift shelter, resulting in more deaths.

A few weeks after these events, state officials made an announcement: For the first time, Louisiana would feature prominently in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York, represented by a 60-foot long “Celebration Gator” float, which would be accompanied by “participants dressed in lavish baby gator costumes.” The float cost $1.4 million and was paid for by the state of Louisiana, which has a minimum hourly wage of $7.25 and one of the country’s highest rates of poverty.

“We hope people from all over the country, and the world, will take part in visiting our lively state where every day is a celebration of life,” Lieutenant Governor Billy Nungesser said in the Office of Tourism’s press release.

The same week saw the publication of a report on the state of the American South during the pandemic. It found that Louisiana had the country’s highest number of disaster declarations as well as the country’s highest rates of anxiety and depression, noting that “climate disasters are likely compounding the crisis.”

These irreconcilable versions of Louisiana weighed on me. I sat on my porch in the days after the storm in the strange quiet of grounded flights and sparse traffic. Sunsets were mesmerizing, as industrial plants spewed toxic gases while the air quality monitoring systems were down; evenings displayed a profusion of stars and the ambient hum of generators. These are moments I’d draw on to define where I live, a place far removed from the “celebration of life” sold in press releases.

We put things back in order around our house and gradually restocked the fridge. People returned and life went on, although the devastation to the hardest hit areas remains. Catching up with friends involved sharing stories, all of which ultimately led to discussing what lies ahead: How are you feeling? Are you thinking of leaving? Where would you go?

I kept thinking about the Celebration Gator.

Andrea Westmoreland [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Andrea Westmoreland [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia CommonsIn 1513, Spanish conquistadors arrived on the shores of what is now commonly referred to as Florida. Led by Juan Ponce de León, legend says they were in search of a fountain of youth, but it’s more likely they were after gold; they found neither. But they did discover an impressive reptile they called el lagarto (“the lizard”), a name later anglicized as “alligator.”

By the 1950s only 100,000 alligators were thought to be left in the US, scattered throughout ten Southern states, the victims of habitat loss and overhunting. They were officially classified as endangered in 1967, and through careful management, the population recovered to about two million today. Untamable, saline intolerant, and flat, they’re good representatives of the Gulf Coast.

Louisiana named the alligator as the official state reptile in 1983. Until then, only three US states had chosen official reptiles; one small lizard and two turtles. The elevation of the American alligator—an apex predator that devours its young whole—was a notable shift.

The following year, the alligator was prominently featured in the Louisiana World Exposition. Neptune, the Roman god of the sea, wrestled the reptile in a promotional poster for the event, which was held in New Orleans and is generally remembered as a financial catastrophe. President Ronald Reagan declined an invitation to the opening ceremony, and Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards called the fair “a disaster,” telling the Press Club of New Orleans, “If this had been a public venture, there would have been people sent to the state penitentiary, there would have been lynchings, hangings, and certainly a lot of investigations.” Attendance projections were drastically inflated. The fair’s debt eventually rose to over $100 million. Before the exposition closed, it would earn the unfortunate distinction of being the first and only world’s fair to declare bankruptcy. (The U.S. hasn’t hosted one since.)

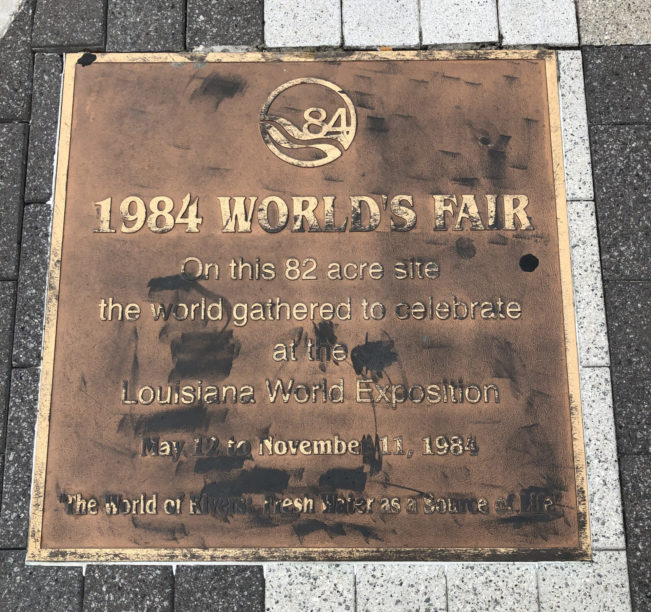

Three decades later, the 1984 fiasco was officially commemorated with a small bronze plaque in a public walkway near Julia Street and Convention Center Boulevard, far from pedestrian foot traffic. I rode my bicycle there one day, and had to search for about ten minutes before I found the plaque. It felt like tracking down a neglected gravemarker, and it was odd to think that such a huge event would be memorialized by a single metal plate set in the ground next to an outlet mall parking lot, bearing the inscription: “On this 82 acre site the world gathered to celebrate at the Louisiana World Exposition.”

photo: Ash Bayer

photo: Ash BayerThe 180-foot tall carousel that loomed over the city is gone, as is the aerial gondola that spanned the Mississippi. The Great Hall, a cavernous, air-conditioned space that featured many of the fair’s exhibits as well as a functioning monorail, became the New Orleans Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, named after the mayor who froze the fair’s bank accounts. The building grew over time, and it now takes up nearly 11 blocks of riverfront property. Still, there’s little physical evidence left of the fair, aside from the plaque and a pair of weathered relics: oversized sculptures of Neptune and an alligator head, situated near an on-ramp outside of the Convention Center.

I’d passed them countless times, but never considered their significance. I wasn’t alive at the time of the fair, and hadn’t given much thought to its legacy, but after Ida and the float announcement my perspective changed. I biked to see the water deity and his reptile companion. They were perched on a dry lawn on the other side of a chain-link fence. The paint on both figures is chipped and dull, and a few of Neptune’s fingers have fallen off. The gator’s eyes are set on the skyline in the distance, a shifting city built on swamp.

photo: Ash Bayer

photo: Ash BayerBy 1986, two years after the ill-fated expo, Louisiana had the country’s highest rate of unemployment. In New Orleans, over 1,000 city workers were laid off and the Port was in the red. After an oil bust, Louisiana had become increasingly reliant on tourism. This year of economic decline coincided with the premiere of Bacchagator, a 105-foot long alligator float that carried riders dressed in gator-themed costumes through the streets of New Orleans during Mardi Gras. Its prow, an enormous alligator head with gaping jaws, was repurposed from the World’s Fair. When the float debuted, it was the largest in the history of Carnival; you might say it’s the direct ancestor of the $1.4 million alligator in the Macy’s Parade.

New Orleans was an early pandemic hotspot, directly linked to the 2020 Mardi Gras celebrations, which had drawn tens of thousands of tourists from around the world. At a time when COVID-19 was still little understood, the disease spread rapidly and disastrously. The Convention Center was turned into an emergency field hospital. Bars and restaurants closed, events were postponed, and the 2021 Carnival season was canceled.

The spring of last year arrived after a year’s isolation. The Convention Center had been repurposed once again, this time into a mass vaccination site. While I sat in an exhibition hall during my fifteen-minute post-shot waiting period, I sent pictures of my vaccination card to friends I hadn’t seen for months. I felt hopeful, and then the delta variant spread, and Louisiana was once again home to the nation’s worst surge in coronavirus cases. Hurricane Ida arrived a few weeks later.

A 12-foot-long, 500-pound alligator killed a 71-year old man wading through floodwaters after the storm, and a different alligator showed up dead in a dumpster. It was in the wake of these events that the Office of Tourism announced that the Celebration Gator would appear in the Macy’s parade.

The surreal part about living in a tourist city reeling from disaster is that the tourists keep coming. Every crisis only seems to increase the need for this to keep happening, a depressing, fatalistic loop that shrugs off catastrophe and frames culture almost exclusively in terms of economic productivity and consumer spending. The bright, shiny float is thus both an advertisement and a diversion, symbolizing a place that doesn’t exist. Anyone can visit, but no one really lives there.