I got in a rumpus with some writers on Twitter last week over the right of libraries to own and lend ebooks. Twitter fights are generally trivial as hell, but not this one. Four of the world’s biggest corporate publishers are suing the Internet Archive over this issue right now, and for anyone who wants the freedom to read, write and publish whatever you want, digital ownership rights matter.

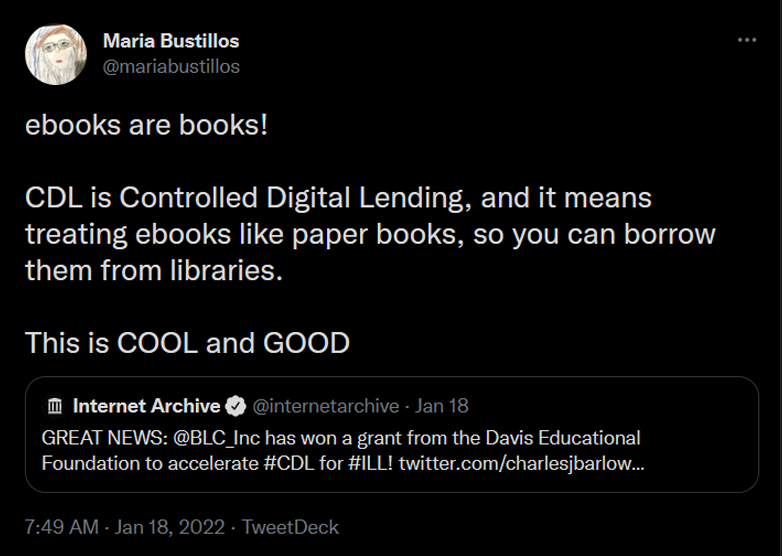

So specifically, this Twitter beef was about Controlled Digital Lending (CDL), a legal framework authored by copyright scholars and lawyers that enables libraries to own and lend ebooks without violating copyright laws, by mimicking the terms of traditional library lending. CDL is rapidly gaining support in the library world.

It works like this:

- a library scans a paper book (that it has already bought, already on the shelves) from its own collection

- the paper book is taken out of circulation and put in inaccessible storage

- now there’s a scanned digital copy—just one!—representing the paper copy (which, again, is in the deepfreeze)

- the digital copy can be loaned to one patron at a time, just as if it were the paper book

- technology controls the loan, so the borrower can’t copy or download; only read

- once the loan period is done, the book returns automatically to the library, and the next user can borrow it

This concept is called “own-to-loan,” and it’s the basis of the system in place at the Internet Archive.

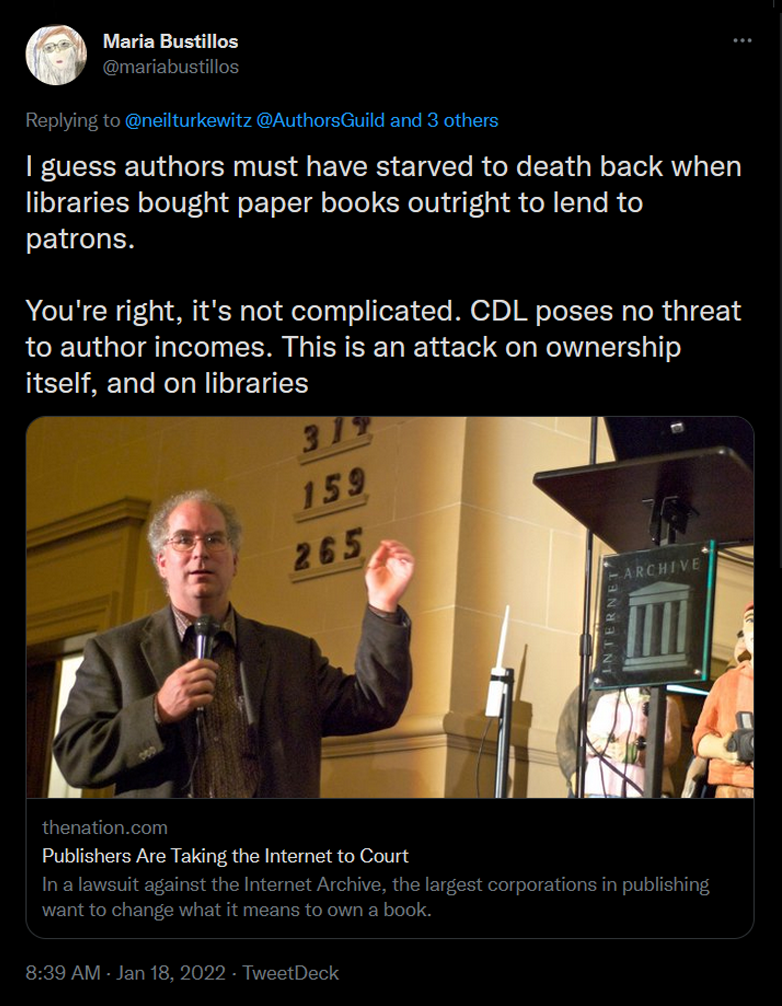

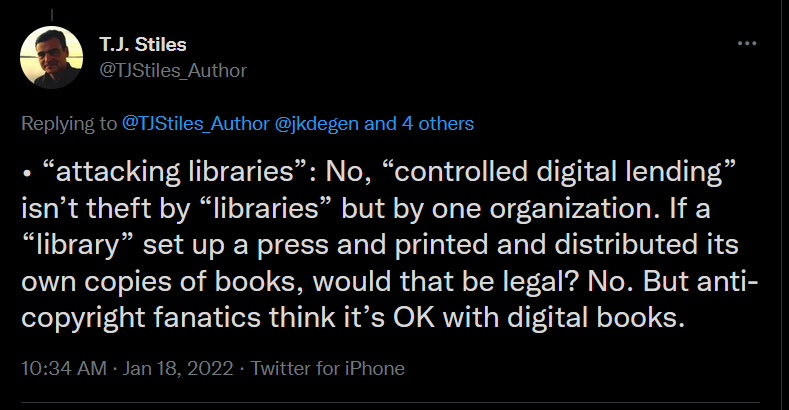

The conversation started like this:

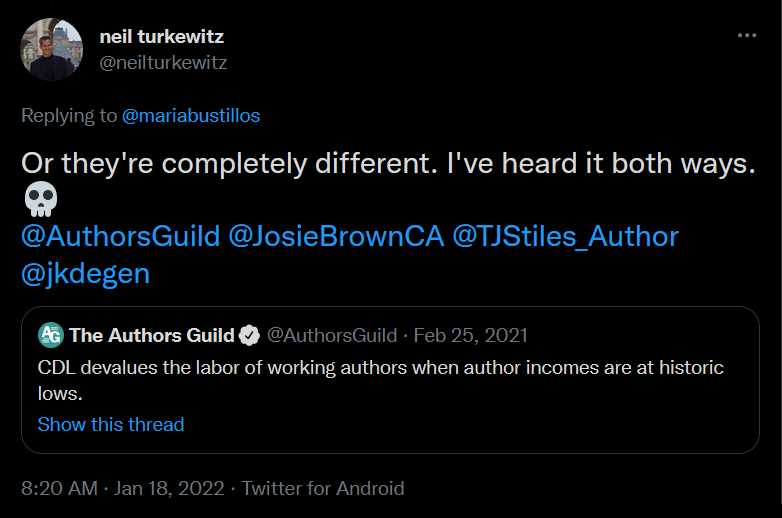

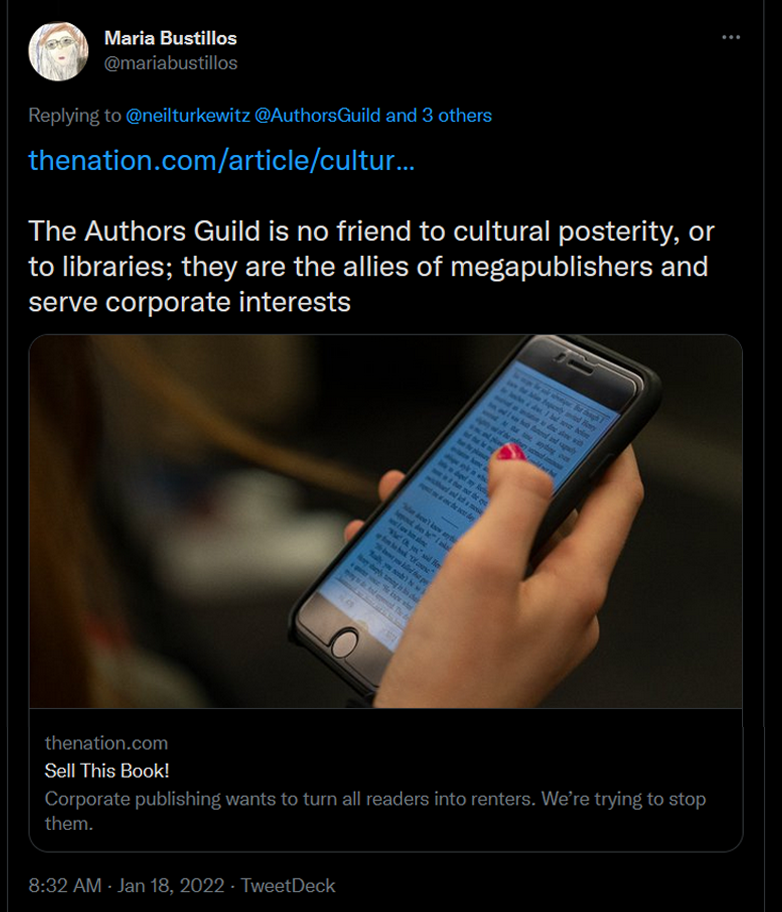

Note that this reply calls in a brigade, two of whom turned up to rumble, and one of whom was the Authors Guild, a trade organization that is famous for suing libraries and losing. When they sued a large digital consortium of university and research libraries (Authors Guild v. HathiTrust), the judge ruled that the copying of ebooks by libraries for preservation, security and search is fair use, a decision upheld on appeal.

This same fight is at the heart of the lawsuit against the Internet Archive. Corporate publishers want ebooks to be categorically different from paper books, so that the laws and protections applying to paper books will no longer apply to ebooks. That way, publishers could choose to rent books to libraries rather than selling them outright.

The trend started with software—you used to be able to own Photoshop and Office, but now you have to rent them—and has spread to movies, music and other media. The perpetual annuity model, needless to say, is very popular with Wall Street. Available evidence suggests that the endgame here, too, is eventually to go over entirely to a books-for-rent model.

As a lifelong fan and beneficiary of libraries, as well as a working writer, I find the suggestion that libraries are trying to steal from writers very very offensive. I see no evidence for it. CDL doesn’t “devalue the labor of working authors” in the slightest. It protects and helps us, by codifying simple rules for preserving our work, and making it legally available to the public to try out through libraries.

The writer Neil Gaiman made a similar point a few years back (though he was defending actual piracy, which I am not crazy about, rather than library lending), noting that few people pay for their first reading of an author. They discover authors through library loans, gifts from friends, and the like, and then go on to buy their books. More than half of patrons surveyed subsequently bought a book by an author they’d first encountered in the library, according to a study published by Library Journal in 2011.

The narrow, greedy concept of copyright as envisioned by corporate profiteers and their enablers isn’t just gross and unethical, it’s false even from a commercial perspective.

There are real risks to preventing libraries from owning books outright: that’s another and equally important question.

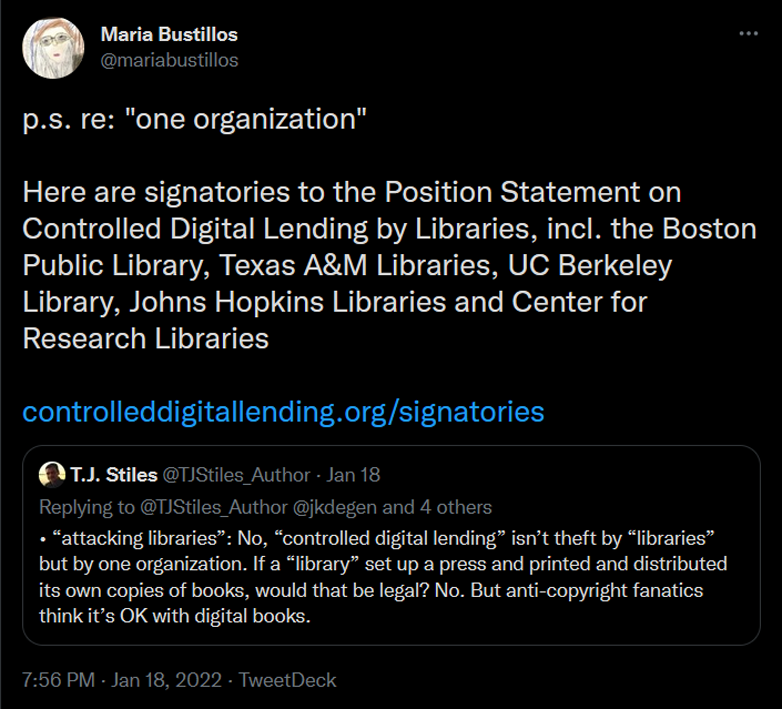

Here are some highlights from this really weird discussion:

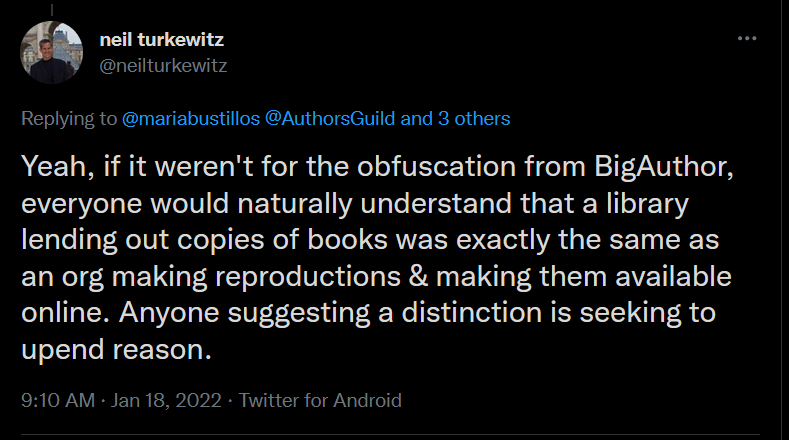

There’s no such thing as “Big Author,” but there certainly is such a thing as “Big Publishing.”

The Big Five publishing houses’ share of the approximately $25 billion book publishing market is estimated at 80%. And it’s Big Publishing that is indeed throwing its weight around by suing the Internet Archive (the “org making reproductions” referenced here, which is actually a California state library and leading institution for digital preservation, not some random “org”).

Again, CDL provides the legal framework for any library to make one copy of one paper book that it owns and loan it to one patron at a time.

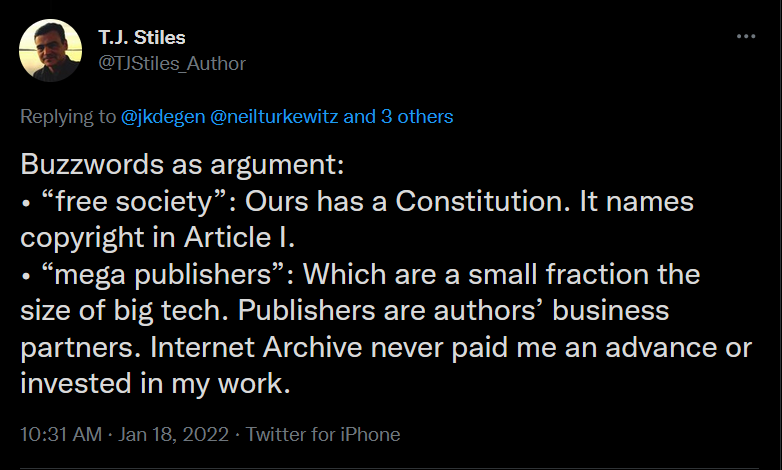

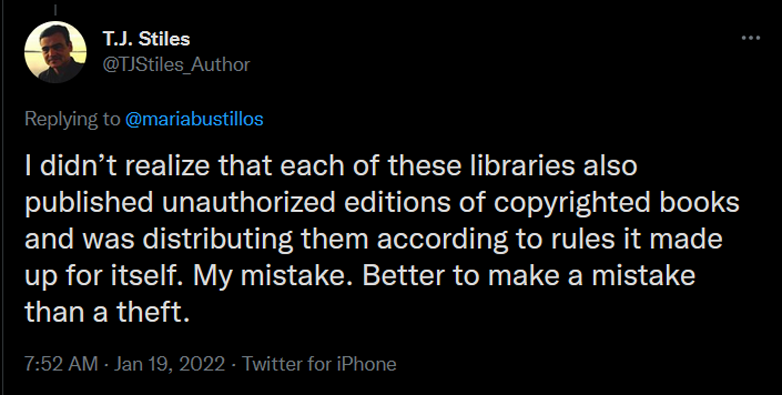

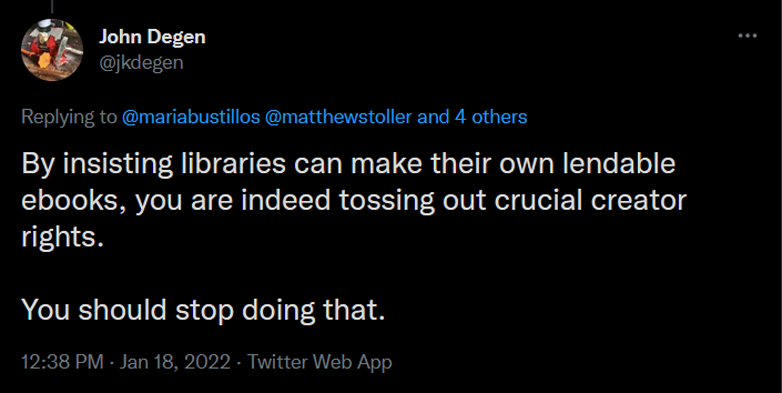

This thing went on forever (Matt Stoller got in there for a second, perplexingly) but I’ll share a bit more of this exchange with T.J. Stiles, whom I later discovered to be an Authors Guild board member. He’s won two Pulitzers and the National Book Award! And his sentiments on the issue of digital librarianship are eye-crossing.

Whoever would conceive of a book as a saleable asset first and foremost isn’t a person who loves books, it’s a person who loves money.

I wrote to T.J. Stiles to ask a few questions, such as whether he really thinks Controlled Digital Lending means “[cutting] off authors’ income from libraries,” because it doesn’t, and I can’t see how anyone could think so. His response was consistent with his tweets, insofar as he ignored everything I said.

Controlled Digital Lending protects writers and publishers, and balances the rights of authors to make a living with the public good. This is obvious! Furthermore, as Neil Gaiman suggests, the likelihood is that library lending increases rather than decreases authors’ incomes by (literally) spreading the word.

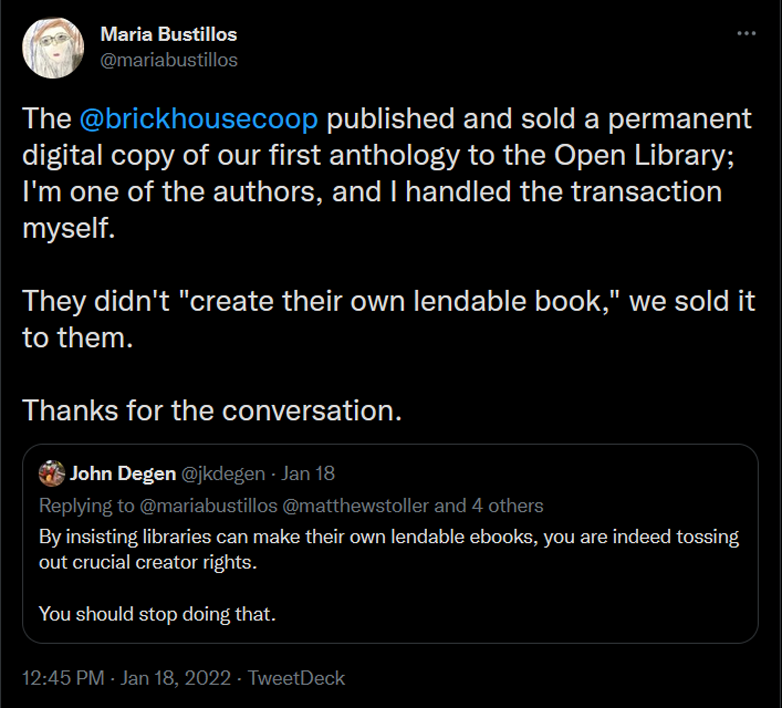

Publishers are free to, and should, sell permanent digital copies of their work to libraries, as we did recently at the Brick House, so that people can see and know that ebooks are books.

Preserving ownership rights for libraries protects writers and artists, and is the linchpin of our cultural future.

Updated 18 May 2022 to remove reference to a completed Kickstarter fundraiser.