THE CHATTER IN my family’s various WeChat groups is mostly Covid misinformation. There are recipes for immunity-boosting soups, all involving various combinations of licorice root, garlic, dried ginger, and green onions; Kuaishou (similar to TikTok) testimonials by people who claim to have had Covid multiple times and are just fine now; useless lists of over the counter medications for fever and congestion—but these medicines are sold out at pharmacies anyway. Mixed in are pictures of rapid Covid tests showing two pink lines. My mother, stuck in America, anxiously sends in stories about elderly persons who had died before the ambulance arrived. Ambulances are another thing that’s become hard to find in China.

No one posts about their fear and frustration. WeChat isn’t the place for that, but it’s the only way I have to get news from my extended family. For millions, messaging apps such as WeChat are the primary point of contact between people inside of China and those outside of the country. Pre-Covid, the divide between inside and out was navigable, with help from airplanes, VPNs, and the confident assumption of progress that globalization promised. After the implementation of “zero Covid”, the divide expanded to an all-encompassing censorship machine. No one writes about their fears, because they fear being made known to the censors.

A timeline is linear. It gives the impression that one thing leads to another. A possible timeline for China’s hastily implemented “opening” could start on the evening of November 24, 2022, when an electrical fire broke out on the 15th floor of a 21-story apartment building in Urumqi, Xinjiang. A video filmed by residents in the adjacent building showed sprays from the firefighters’ water cannons falling away without ever reaching the growing flames. A quick pan indicated the problem: barricades and parked cars had blocked the fire trucks’ progress through the apartment complex. It took three and half hours to fully extinguish the fire. The official figures were ten dead, nine injured.

The next night, as the news spread—of the fire, its deadly toll, and the ineffective rescue—residents across Urumqi, which by then had endured more than three months of draconian lockdown controls, left their apartments, broke down quarantine barriers, and walked through the city’s streets. More videos were filmed and circulated, of people walking in groups outside, with some singing China’s national anthem, “March of the Volunteers.”

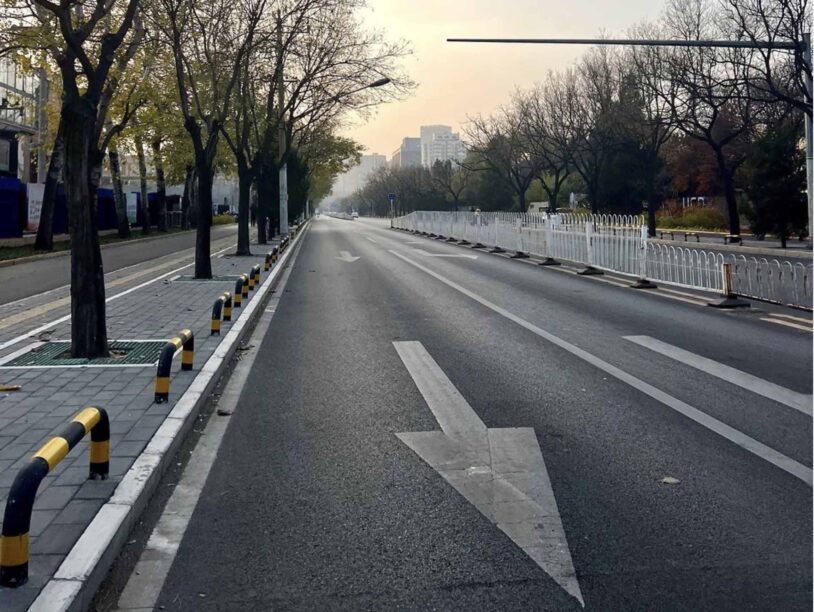

In San Francisco, I watched the videos and felt shock at the unfamiliar normality of what they showed: groups of people, in a city, walking and singing. Just two days earlier, a friend in Beijing had breached their self-imposed social media silence and posted to Instagram a series of photos of the Chinese capital’s streets emptied of people, cars, even trash. There was no sign of human activity. The images were beautiful but distressing. The streets of a metropolis of 22 million people are never empty by choice.

After that night in Urumqi, people in other cities also left their apartments and gathered in the streets. They were defying the rules against such assemblies, but “zero Covid” meant there were rules against nearly everything. On November 26, late in the evening, a makeshift memorial at the corner of Urumqi Road in Shanghai became a vigil, which swelled into a protest, drawing crowds and, finally, police. For days afterward, from other cities in China and around the world flowed a steady stream of videos and images of people gathering together, yelling and chanting, or silently holding up pieces of white paper. The pretense that “zero Covid” was working fell away.

Officially speaking, the first of China’s new Covid policies were announced on December 7, 2022, one day after the state funeral for Jiang Zemin. China’s National Health Commission announced a 10-point plan, accompanied by a declaration of victory against Covid and new scripts from the same old experts who now wanted the public to know that the Omicron strain only caused mild illness and little to no physical organ damage.

Seemingly overnight, the pandemic ended for the Chinese people. The previously ubiquitous testing kiosks were dismantled and carted away. Mandatory quarantines were ended, even for those showing symptoms. The system of electronic health codes that dictated the scope of one’s movements and regulated entry to all public facilities was abandoned. People could go where they wanted, when they wanted.

But SARS-CoV-2, the virus, never went away. By mid-December, references to sheep were suddenly everywhere. The reason being the Chinese character for sheep, 羊, pronounced yang, is a homonym for 阳, the character that denotes a positive test result. And having done away with the surveillance testing, contact tracing, and quarantine requirements—the few constructive public health policies actually enacted during “zero Covid”—nobody, not even China’s CDC has reliable numbers about Covid infections and deaths anymore.

Even so, the discrepancy between estimates and published numbers is staggering. In an interview conducted on December 31, 2022, the administrator at Shanghai’s premier research hospital estimated that 70 percent of the city’s population had been infected in the latest wave. It was more like a hunch extrapolated from emergency room and Covid clinic admissions rates. Still, for a city like Shanghai, that would mean nearly 18 million people had contracted Covid between December 8 and December 31, an incredibly elevated infection rate that required a large, existing population of Covid patients. Yet officially, China’s CDC only reported 1.27 million hospitalizations and 59,938 deaths from December 8, 2022, to January 12, 2023, for the entire country.

Just before Christmas, a message arrived from my friend Yu, a former investigative journalist turned researcher. It read simply, “I made it out.” And I knew immediately what he meant and where he might be and that he would need time to settle into a new life. Some might call that being a good friend. But he would say it’s just the reality of being a fellow fugitive from your own country.

When we finally talked via video chat, after the New Year, I asked Yu why he decided to leave China now. He had been talking about the possibility of moving away for years—when he got married, when he became a father, when his employer went public and he had a little bit of money. But the date of departure kept being pushed to the future. I didn’t ask why he hadn’t left sooner. Why he had stayed to the bitter end of “zero Covid,” after all. He took out a cigarette and lit it. He had been trying to quit for decades, since at least 2002.

Our conversation was circular and oblique. No names, few specifics. But so much became clear. He was sinking deeper into a depression. China had become unrecognizable to him; even his darkest visions hadn’t included the country grinding to a near standstill for three years. Not wanting to jeopardize his family, he stayed home during the protests, following the news as it unfolded on social media and disappearing updates. He made the decision to leave China in a panic, haunted by memories of so many protests brutally put down, of friends arrested, bodies on the ground. He showed me the house he and his family were living in. It was in a nice and quiet neighborhood. The rooms were nearly empty, but there was a garden and a weathered play structure in the backyard. He didn’t name the street or tell me his address. I didn’t ask. I’ll know if it ever becomes necessary.

China’s pivot from “zero Covid” to a policy of “whatever” was rapid and chaotic. But from the perspective of a ruling political party trying to recoup its grasp on the country, the public health failure was also a successful expansion of political control. For three years, with no opposition and little dissent, the Chinese government built up a sophisticated system that monitored the physical movements of all persons within its borders. Its propaganda machine made people fear the idea of Covid and feel ashamed when they tested positive. Most significantly, Xi Jinping succeeded at becoming President and Party Secretary for an unprecedented third five-year term.

As the protests spread from city to city, the response outside of China was astonishment and a cautious hope. In 1989, the Tiananmen protests became known largely through the reporting of foreign journalists. The demonstrations in November were documented by the participants themselves, who filmed and transmitted their perspectives and experiences in real time. The smartphones in their hands amplified and broadcasted their discontent, but also served as beacons by which the police identified and tracked them. The protests petered out after the end of “zero Covid”; gathering meant a new set of dangers. Soon after, the arrests began, and people started disappearing. Then this week, China’s Vice-Premier Liu He is back in Davos, Switzerland, soliciting foreign investments at the World Economic Forum. The real “normalization” of China is now underway.

Thank you for visiting POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!