Pity the poor billionaire who has been insulted by an unfriendly journalist, his invincible amour-propre cruelly wounded, a maligned and suffering soul. Such a man (it is generally a man) might easily develop a willingness to pay for his revenge in court. Peter Thiel’s long-sought destruction of Gawker Media in 2016—achieved through the unlikely offices of the disgraced wrestler Hulk Hogan—is a recent retelling of this story, the broader implications of which have yet to be fully analyzed or understood.

But in the record-breakingly hot London summer of 1976, a strikingly similar rumpus went down between the aggrieved tycoon Sir James Goldsmith and the satirical magazine Private Eye. Instead of a sex tape and a washed-up wrestler, there was a washed-up gambler on the lam—an aristocrat accused of murder, whose attempt to escape arrest might (or might not) have ended in his being eaten by a tiger in a private zoo.

Improbable as it may seem, a comparison of the two scandals has a lot to tell us about the protection of press freedom in 2018.

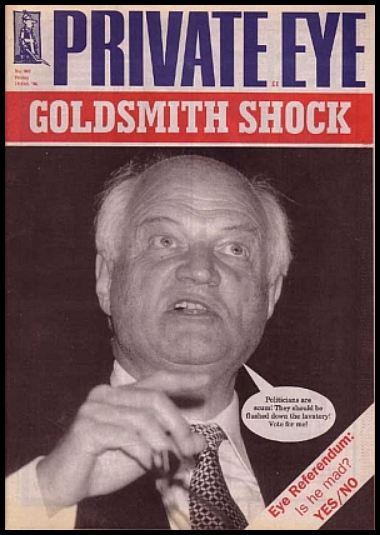

“It is often left to Private Eye to ask the awkward question,” observed Richard Ingrams, the magazine’s founder and editor, in Goldenballs!, his lively 1979 account of the Goldsmith affair.

The awkward question in this case concerned the 1974 murder of Sandra Rivett, nanny to the children of John Bingham, seventh Earl of Lucan, known to his friends as Lucky. Sandra Rivett was beaten to death with a lead pipe while making tea in the Belgravia home of Lucan’s estranged wife Veronica, Lady Lucan. Newspaper accounts were generally agreed that Lord Lucan was the murderer, and that he had killed Ms. Rivett by mistake, the intended victim having been Lady Lucan—whom he attacked next, but not so fatally. He then drove off to the house of a friend, and after that he was never seen again.

The mystery remains unresolved. Lady Lucan died in late September 2017, and maintained to the end that her husband was the murderer. A number of Lucan’s friends believed him to be innocent. Dozens of theories and testimonies emerged over the 43 years after his disappearance: he’d tossed himself under the propellers of the Newhaven-Dieppe cross-Channel ferry; he’d been spirited away to Africa; he’d shot himself and afterward, been fed to the aforementioned tiger in the private zoo belonging to his great friend, the gambling club owner John Aspinall.

The Clermont Club, Aspinall’s fancy London gambling den, was home to an inner circle called “the Clermont Set.” This loosely-constituted posse included Lucan, Mark Birley, Peter Sellers, Jim Slater, Lucian Freud, Ian Fleming, and Sir James Goldsmith. Also one Dominic Elwes, the “court jester” of the group, a wit and sometime painter who was often down on his luck and prone to depression. After Lucan’s disappearance, the Sunday Times paid Elwes a couple of hundred pounds to talk about (and illustrate) a lunch at Aspinall’s house in London, where the group had discussed how they might help their friend, “Lucky,” after the murder.

But when Birley and Goldsmith got wind of Elwes’s blabbing to the Times, they kicked him right out of their club. In his despair Elwes took an overdose of barbituates, leaving a suicide note reading, “I curse Mark [Birley] and Jimmy [Goldsmith] from beyond the grave. I hope they are happy now.”

The publicity surrounding Elwes’s suicide came at an unwelcome time for Goldsmith, who had recently taken over the chairmanship of Slater Walker, a massively-cratering financial concern that had been bailed out to the tune of over £110 million of public money. Goldsmith had become just the sort of figure to attract the interest of Private Eye: an entirely “respectable” magnifico with some really filthy laundry to air. A story commissioned by Ingrams appeared in the magazine on 12 December, 1975: “All’s Well that Ends Elwes,” under the byline of Patrick Marnham.

“From the beginning, the police have met obstruction and silence from the circle of gamblers and boneheads with whom Lord Lucan and Dominic Elwes associated,” Marnham wrote. Of Goldsmith: “he is a cousin of the French Rothschilds and is known for his ability in dressing up the balance sheets of his various companies whereby large sums are transferred from one company to another for purposes which are not clear to outsiders.” Then came the sad tale of Dominic Elwes, and a characteristically ironic Eye-style conclusion: “[T]here seems to be no reason to question the Bank of England’s stated confidence in [Goldsmith] as a man of integrity, well fitted to guide the helm of a great public enterprise.”

Other Private Eye articles critical of Goldsmith followed in quick succession. Financial reporter Michael Gillard connected the dots regarding Goldsmith’s concealed personal friendship and business dealings—and there were a lot—with Clermont Set crony and disgraced asset stripper Jim Slater, of the fallen Slater Walker. Through his lawyer, Eric Levine, Goldsmith was also linked with a man named T. Dan Smith who’d been sent to prison for bribing politicians.

A few days after the T. Dan Smith article appeared, Goldsmith issued a blizzard of writs against Private Eye: Sixty-three against the magazine itself, plus another thirty-seven against its distributors. He also filed documents in court to sue Ingrams for Criminal Libel over the Elwes article, a case that could land Ingrams in the clink.

Having obtained sworn statements from sources willing to testify to the truth of what they’d written about Goldsmith’s lawyer, Eric Levine, the Eye crew went along to court to take their chances. Things seemed to favor the defense, until their witnesses suddenly clammed up and refused to testify at all. These same witnesses later submitted new statements (one of which had been typed on Goldsmith’s typewriter) cravenly apologizing for having told Private Eye “a pack of lies.” That Goldsmith had brought some kind of pressure to bear on the defense witnesses seemed obvious, but was never proved. “I never realised they were so powerful,” one of them later told Ingrams. Hearings, writs, injunctions and appeals flew thick and fast through the courts for over a year.

Peter Thiel’s involvement in Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit against Gawker Media was revealed (by Thiel himself, some have conjectured) only after it was all over. On October 4, 2012, Gawker published a clip of blurry security-camera footage depicting Hogan engaged in sexual intercourse with Heather Clem, the wife of a friend. Hogan claimed that the publication had invaded his privacy and caused him intense emotional distress. Gawker contended that Hogan, who had discussed his sex life publicly and in lurid detail—on the Howard Stern radio show, for example—had himself made the topic a matter of public interest.

This lawsuit was a last-ditch effort that came on the heels of Hogan’s earlier failure in federal court: In December 2012, U.S. District Court Judge James Whittemore ruled for Gawker, citing the Eleventh Circuit’s recognition that “the balance between the First Amendment and copyright is preserved, in part, by the doctrine of fair use.” The Hogan team then added Gawker to a separate suit, filed previously in a Florida state court against Heather Clem and her husband, both of whom were later dropped, leaving Gawker as the lone defendant.

The Pinellas County jury eventually awarded Hogan compensatory damages of $115 million, plus $25.1 million in punitive damages (later reduced to a total of $31 million), as compensation for his emotional distress and invasion of privacy. And throughout the trial, to its conclusion, nobody knew that the Hogan side had been funded all along by the billionaire Paypal founder and prominent Trump supporter Peter Thiel.

Some weeks later Thiel told the New York Times that years before, he’d hired a team of lawyers “to look for cases” against Gawker Media “that he could help financially support.” These lawyers worked in secret, filing an unknown number of lawsuits against Gawker; the billionaire spent upwards of $10 million before the Hogan suit finally brought the company down. [Full disclosure: I wrote a few freelance pieces for Gawker.]

One of the most regrettable aspects of this story, and one of the least commented-on, is that press accounts consistently favored Thiel’s version of events over that of their own colleagues at Gawker, even after it was clear that Thiel and his lawyers had been the ones conniving against journalists in secret. For example, the press unquestioningly reported (and continues to report) Thiel’s claim that his desire to punish Gawker stemmed from their having “outed” him as gay in 2007.

Far more convincing evidence suggests instead that Gawker savagely wounded Thiel’s ego—a potential motive for revenge scarcely ever mentioned in press reports. Owen Thomas, who wrote the 2007 “outing” piece in question, has repeated ad infinitum that Thiel’s sexuality “was known to a wide circle” in Silicon Valley. In order to be outed, one must first be in. But there can be no doubt that Gawker and its Silicon Valley publication, Valleywag, were merciless in their taunting of Thiel, and it went on for years. They mocked him for his political support of rabidly anti-gay Ted Cruz; for losing six billion dollars in his hedge fund, Clarium Capital; for supporting the right-wing prankster James O’Keefe; for “spinning so much bullshit, he can’t even get his facts straight” and for funding a floating libertarian-utopia (“seasteading”) construction project. Also for paying kids not to go to college and for wishing women couldn’t vote, and this list is far from complete.

Accusations of “outing” against a publisher, however, are all but certain to be met with public opprobrium. In other words, accusing Gawker of homophobia could cast Thiel as the appealing victim, the underdog, in the court of public opinion. But hardly anyone pointed this out, or accused him of framing his own motives in a self-serving way. Indeed the New York Times gave Thiel a whole Op-Ed in which to make his own case—and poorly. “A free press is vital for public debate,” he wrote, inducing multiple aneurysms in longtime observers of this drama. “…[E]xercising judgment is always part of the journalist’s profession. It’s not for me to draw the line, but journalists should condemn those who willfully cross it.”

True. It was not for Peter Thiel to draw the line—but he drew it anyway. With few exceptions, the media let that go unchallenged.

Because one rich man willed it, millions of people can no longer read Gawker. The right answer for Peter Thiel, if he didn’t like Gawker, was to steer clear of reading it—not to deprive the rest of the world of the right to do so.

The press’s treatment of Gawker editor A.J. Daulerio, who wrote the post at issue in the Hogan trial, was still more detrimental to the cause of free speech in America. A careless, insolent remark Daulerio made in deposition was denounced far and wide, again and again, by tame journalists whose failure to defend their Gawker colleague risked—still risks—a grave cost to us all. Hogan’s lawyers asked Daulerio: Was there any sex tape he would consider not newsworthy? One involving a child, he replied impatiently. How old a child? In an expression of sheer contempt for both question and questioner, he said: “Four.”

It was a coarse, shocking remark, meant to insult. But in no universe is it possible that A.J. Daulerio meant to suggest that he would willingly publish a toddler sex tape. Think for a moment. It would be a felony even to possess such an unspeakable thing, let alone publish it. Why would any reporter write about this deposition without condemning Hogan’s lawyers—without denouncing, angrily, even the suggestion that Daulerio could have meant such a thing literally? But no, paper after paper repeated Daulerio’s juicy “gaffe,” ad infinitum, and with no meaningful defense of the speaker, with no logical analysis of what his words might really have meant—not only at the Post, but at the Times.

Why did the press choose to omit the more credible motives ascribable to the various players in this drama, and to slant their reporting against their own colleagues at Gawker? This question is especially pertinent given that so many legal specialists reckoned Gawker to be on the right side of the law in the Hogan case, and gave them a good chance of prevailing on appeal, as they had in federal court.

Two reasons spring to mind. One is that, at least until very recently, wealth has by some mysterious sleight-of-hand become confused with respectability, and even with intelligence, in the mind of the American public, so that the rich are automatically identified as pillars of society. Silicon Valley billionaires such as Thiel, an early investor in Facebook, were—again, until very recently—often portrayed as magicians, invincible geniuses who were “changing the world,” and unquestionably for the better. The vast alterations made in our culture by the tech titans who brought us Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Google gave them an almost priestly impunity in the press. If you didn’t like them it was only because you were jealous, or lacked a sense of the future. Only now, in the wake of the debacles that took place at Facebook and Google in the 2016 election, after the collapse of Theranos and growing signs of mistrust in Tesla, Uber and Amazon, has this triumphalist narrative begun to unravel.

The second reason for our media’s acquiescence to power is the abject and quite understandable fear of being the next target of an angry rich man’s wrath. Any journalist can tell you stories about having had pieces killed because an editor and/or publisher determined that the cost of potential legal trouble simply wasn’t worth the public benefit (or traffic, or shock value) to be got by publishing. This is a business decision, always; it isn’t a matter of what’s true, or even of what you have on the record. It’s also a matter of the vindictiveness of the target, of his or her wealth, and now—this new, Thiel-inflected consideration—of a deep-pocketed adversary’s willingness to squander that wealth, win or lose, simply for the sake of harming a journalist, a publication, or the press in general.

On the publishing side, resources are always limited, and the calculation is often a thorny one (as can easily be seen, for example, in the story of Harvey Weinstein, so many painful, careful, risky years of newsgathering in the making.)

But now the vultures are coming home to roost, in Silicon Valley as in Washington. Thiel’s full-throated support of Trump—he spoke at the 2016 RNC convention—is starting to look more catastrophic than visionary. The unsavory roles played by Facebook and Google in the 2016 election are only now beginning to be investigated at all seriously. And the princes of Silicon Valley are beginning to look a little wobbly on their various thrones.

The similarities between Jimmy Goldsmith and Peter Thiel are neverending. Two monstrously rich men, each with an inflated opinion of his own intelligence, ability, and fitness for leadership, not just in business, but in world affairs—two titanic snobs of grossly limited intellectual range—two boyish psyches suffused with romantic right-wing views, each seeing the world in terms of a storybook, each one his own hero, each couching his throwback, paternalistic ideas in fantastically clumsy, melodramatic language.

“Isn’t it rather curious for someone in your position […] to start fussing about what one or two journalists say about you in the press?” an interviewer asked Goldsmith in the summer of 1976, when the Private Eye writs were flying. Goldsmith was then in his early forties; tanned and handsome in a louche way despite his baldness, he was already very rich, a right-wing food and diet-supplement magnate, a playboy, a gambler and bon vivant.

“People like you say we should be Tolerant,” he replied, so pompously as to require initial caps for accuracy. “And Tolerance is a tremendous Virtue. But the immediate Neighbors of Tolerance are Weakness and Apathy…. Tolerance of Extremists who are trying to Destroy our Society is Not a virtue. I believe it is Cowardice and Treason.” (n.b. what he’s saying here is that Private Eye is trying to destroy society.)

Compare the pontifications of Peter Thiel, from a Cato Unbound essay he published in 2009: “[I]n the 1990s, I began to understand why so many become disillusioned after college. The world appears too big a place. Rather than fight the relentless indifference of the universe, many of my saner peers retreated to tending their small gardens. The higher one’s IQ, the more pessimistic one became about free-market politics […] Those who have argued for free markets have been screaming into a hurricane… For those of us who are libertarian in 2009, our education culminates with the knowledge that the broader education of the body politic has become a fool’s errand.”

Both men cast themselves as noble, daring outsiders—Goldsmith as a womanizing, buccaneering English aristocrat; Thiel, a visionary techno-genius from the pages of Ayn Rand. Both despaired of educating an ignorant public. There’s a common preoccupation with the End Times, too. Goldsmith helped publish an apocalyptic tract in the Ecologist magazine outlining the aftermath of the coming collapse of industrial society; Thiel, in addition to his sometime support of seasteading and space travel, has acquired New Zealand citizenship, a Queenstown mansion, and a “spectacular 477-acre freehold estate set on the western shores of stunning Lake Wanaka,” joining, as the Guardian put it, “a growing band of wealthy Americans seeking a haven from a possible global apocalypse.”

Public criticism goaded both Goldsmith and Thiel into vendettas against the press that cost them fortunes and lasted for years. The result, in both cases, was a personal and professional comedown of a kind recalling the comic-book proverb: Who seeks revenge should begin by digging two graves: one for his enemy, and one for himself.

But here’s the big difference between the Goldsmith/Private Eye case and the Thiel/Hogan/Gawker one: a substantial portion of the UK press, public and business community didn’t care to see journalists being kicked around by a thin-skinned rich guy in 1976. Private Eye had the benefit of enlightened readers who stepped up to the plate—among them, even some who’d been the magazine’s targets in the past.

In Goldenballs!, Ingrams describes his horror when, unexpectedly, Mr Justice Wien permitted Goldsmith’s criminal libel action against Private Eye to go forward; this was the moment Ingrams learned that he himself might really land in prison. “To say that my heart sank sounds melodramatic,” he wrote. “But something of the kind occurred.”

When I got back to Private Eye there was another surprise in store for me. “Tiny” Rowland, Chairman of the huge mining conglomerate Lonrho, wanted me to ring him. I dialled the Lonrho offices and asked to speak to the Chairman. ‘Mr Ingrams,’ he said, ‘I’ve just heard about the case on the lunchtime news. I want to offer you my support. There will be no quid pro quo. You must go on writing about me whenever you want. You can have £5,000—whatever you want.”

I managed to stutter out my thanks.

Ordinary readers of Private Eye stepped up too, to contribute to the “Goldenballs Fund” set up to gather money for the heavy legal costs of defending the case.

I am a London taxi-driver. I often read Private Eye and sometimes I am amused, amazed at your revelations, shocked at your lack of concern at some of the undoubtable inexactitudes and disgusted by your sometimes obscene phraseology. However I will be damned if I will allow any one man to stifle one of the very few politically or economically uncontrolled magazines left in this country.

And Goldsmith found public opinion turning against him where it counted most: in his business dealings. His attempts to buy a newspaper of his own were blocked over and over, sometimes because journalists refused to work for him, and sometimes because he’d made enemies of the papers’ owners. Eventually he began to indicate a willingness to settle with Private Eye.

In case you think that, unlike the satirical website Gawker (“tabloid trash,” “human garbage” “mean girls” etc.) Private Eye’s support came because of its sterling reputation among the UK reading public, I assure you this was not so. Private Eye has always had its passionate detractors as well as fans. This 2001 squib from the Guardian was, and is, typical:

Sneering, smug homophobic, vicious and parochial: Private Eye has been accused of being all of these things, with some cause… [T]his cheaply produced and tatty-looking magazine … gives every impression of having been written by a gang of public-school boys [i.e. private schoolboys] entirely for their own amusement.

Support for Private Eye came because of enlightened taxi drivers and millionaires who didn’t like the idea that any random rich jerk with a grudge could determine what they could or couldn’t read. In the end, they’re the ones who forced Goldsmith to settle with Private Eye for a nominal sum in October of 1977.

Private Eye enjoyed the biggest circulation numbers in its history late last year.

On its face, even today the Hogan/Gawker case seems ludicrously prurient, outlandish, an anomaly in every way. The dizzyingly unpleasant spectacle involved a DJ named Bubba the Love Sponge and his swinging wife, Heather Clem, plus an FBI sting, a vicious pack of pontificating lawyers, and the tragicomic scene of Nick Denton reading A.J. Daulerio’s barbed commentary on Hogan’s genitals in a Florida courtroom. So easy, then, for members of the “respectable” press to dismiss the case and gloss over the importance of protecting Gawker’s claims. But that was a mistake.

Our shambolic government has made no secret of its hostility toward the press.

When the press itself begins to obey the powerful, in the apparent conviction that power deserves respect, our chance of spreading the truth is lost. To my mind anyone who thinks this way should find a different job, and pronto. But if the people of this country pay attention to what has happened—and I think that’s starting, now—we can protect our speech rights, and press freedom.

Peter Thiel admitted as much to the Times: “It’s not for me to decide what happens to Gawker,” he said. “If America rallies around Gawker and decides we want more people to be outed and more sex tapes to be posted without consent, then they will find a way to save Gawker, and I can’t stop it.”

It’s not hard to read between the lines. What applies to Gawker applies to all media. Even someone as self-regarding and as blind to the meaning and value of the First Amendment as Peter Thiel is aware that ultimately, the only thing that can defend the free press from its enemies is a people willing to protect its journalists, and to insist on its own right to be informed.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Issue 56 of the Columbia Journal.

Popula was phenomenal last week, if you’re game for a few more.