Kaoliang (高粱), a high-proof fermented sorghum wine drunk in Taiwan and China, belongs to the category of alcohols usually referred to in China as baijiu (白酒), though the term baijiu is less commonly used in Taiwan. It’s generally drunk by older men; I seem to be one of the few people under fifty I know who drinks it.

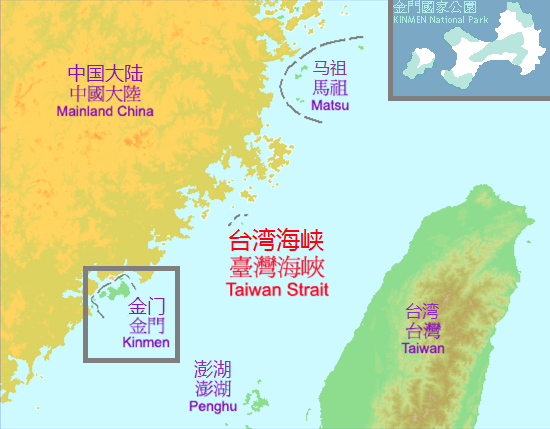

The best known Taiwanese kaoliang is produced on the outlying island of Kinmen, part of the territory administered by the Taiwanese government. However, China is literally in viewing distance of Kinmen. As a result, identity trends in Kinmen are distinct from the Taiwanese mainland. If Taiwan is already a peripheral, marginal place as the result of its lack of official acknowledgment by the majority of the world’s nations, this is even more true of Kinmen, which is caught uncomfortably between Taiwan and China.

Kaoliang is clear, looks deceptively like water, and ordinarily comes in two strengths: 38 percent alcohol and 58 percent. It goes down quite smoothly but then leaves an aftertaste like castor oil. Given its high alcohol content, drinking kaoliang is often a sort of masculinity ritual among older men to see who can drink the most.

This may be part of the reason why drinking kaoliang is on the decline among younger Taiwanese, though I am not sure whether Taiwanese young people drink less than their elders; those who stick to water on drinking occasions often jokingly claim that they are drinking kaoliang. But the association of kaoliang with masculinity is real, as one can see in the association of kaoliang with blood, soil, and masculine violence (in particular against women) in Mo Yan’s Red Sorghum, the best-known work of the Chinese Nobel Prize-winning author, which was adapted into a movie in 1988 by Zhang Yimou, and into a television series in 2014.

Young people drinking kaoliang seem to me to be affecting a working-class habit, like chewing betel nut. One sees this at punk rock shows, for example, or among activists verging towards the radical chic; a way for young people—usually men—to assume the trappings of working-class masculinity.

I personally have had little interest in playing up my working-class credentials or trying to come off as a tough guy through drinking kaoliang, but my drinking kaoliang did, in fact, have to do with relative poverty. Of all the hard liquors available in Taiwan, kaoliang definitely has the highest alcohol content relative to its price. A 100-milliliter bottle of 58 percent alcohol kaoliang usually costs only 59 NTD at a 7-11, for example, a little under $2.00.

Brian Hioe

Brian HioeThe highest period of kaoliang consumption in my life was in January 2016, a period in which I was struggling to complete my MA thesis while also conducting on-the-ground reporting on 2016 presidential and legislative elections and interviewing political candidates. This was among the most stressful periods of my life; my advisor attempted to change my MA topic two weeks before graduation, despite my having spent close to two years researching the topic. This put my MA status in limbo, and led me to consider withdrawing from my program. Also the 2016 elections were highly dramatic. Every day it seemed there was a new scandal, sudden protests, or rallies by far-right-wing political groups.

So, it may not have been too advisable, but alcohol was my way to get through all this. Part of it came from the need to dull literal physical pain; part of it came from the need to just release stress. There are no laws against public drinking in Taiwan. When I finished my work for the day, I spent a lot of time wandering through Taipei city streets with a bottle of kaoliang in hand, lost in Baudelairean flâneur-ing through the many small alleyways of Taipei as I drifted slowly home after the subways closed.

Thankfully, I’ve managed to cut down on my alcohol consumption since then. Nowadays, whenever I encounter another young person who regularly drinks kaoliang as something other than an affectation, I suspect that that person is an alcoholic.

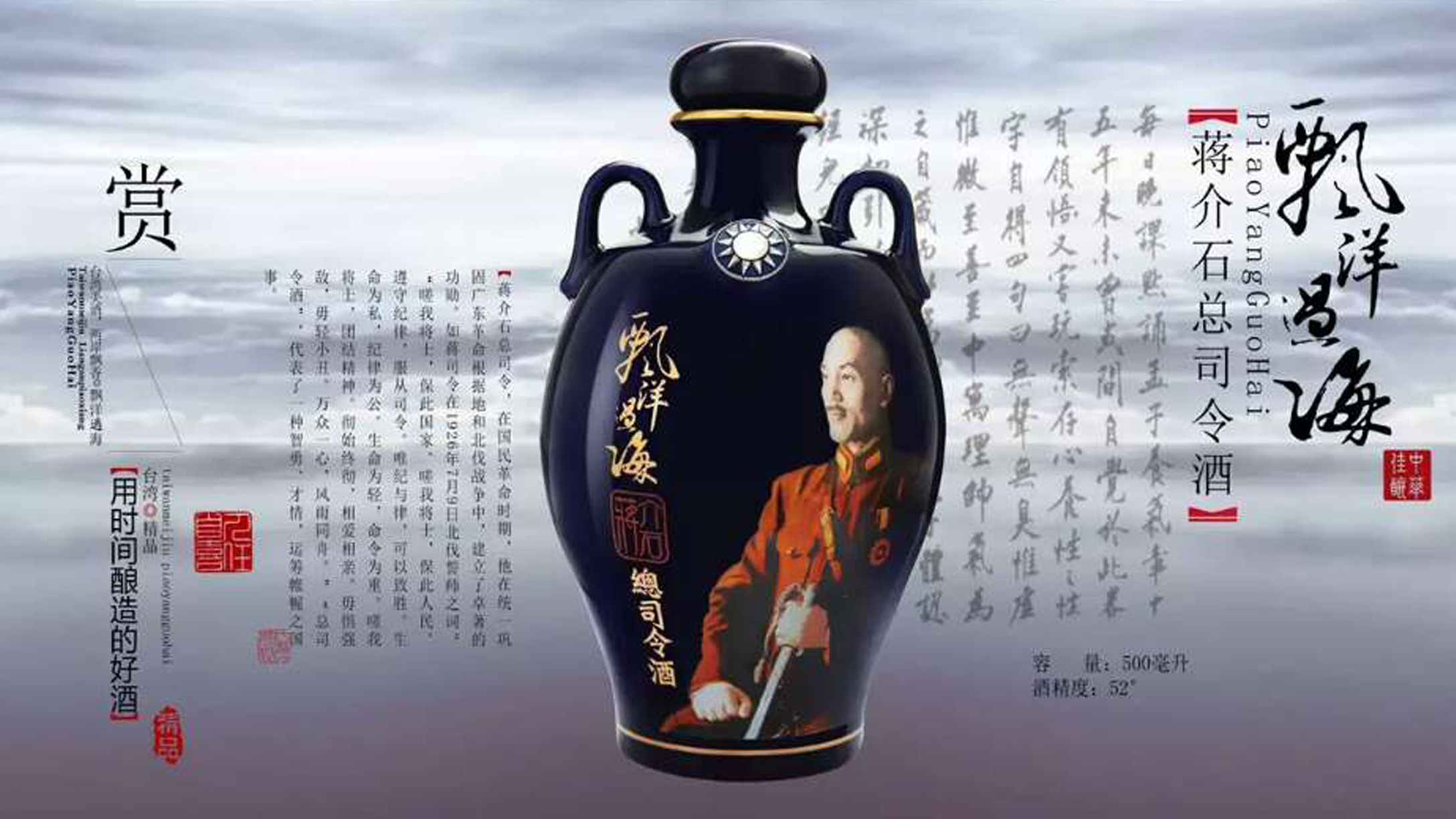

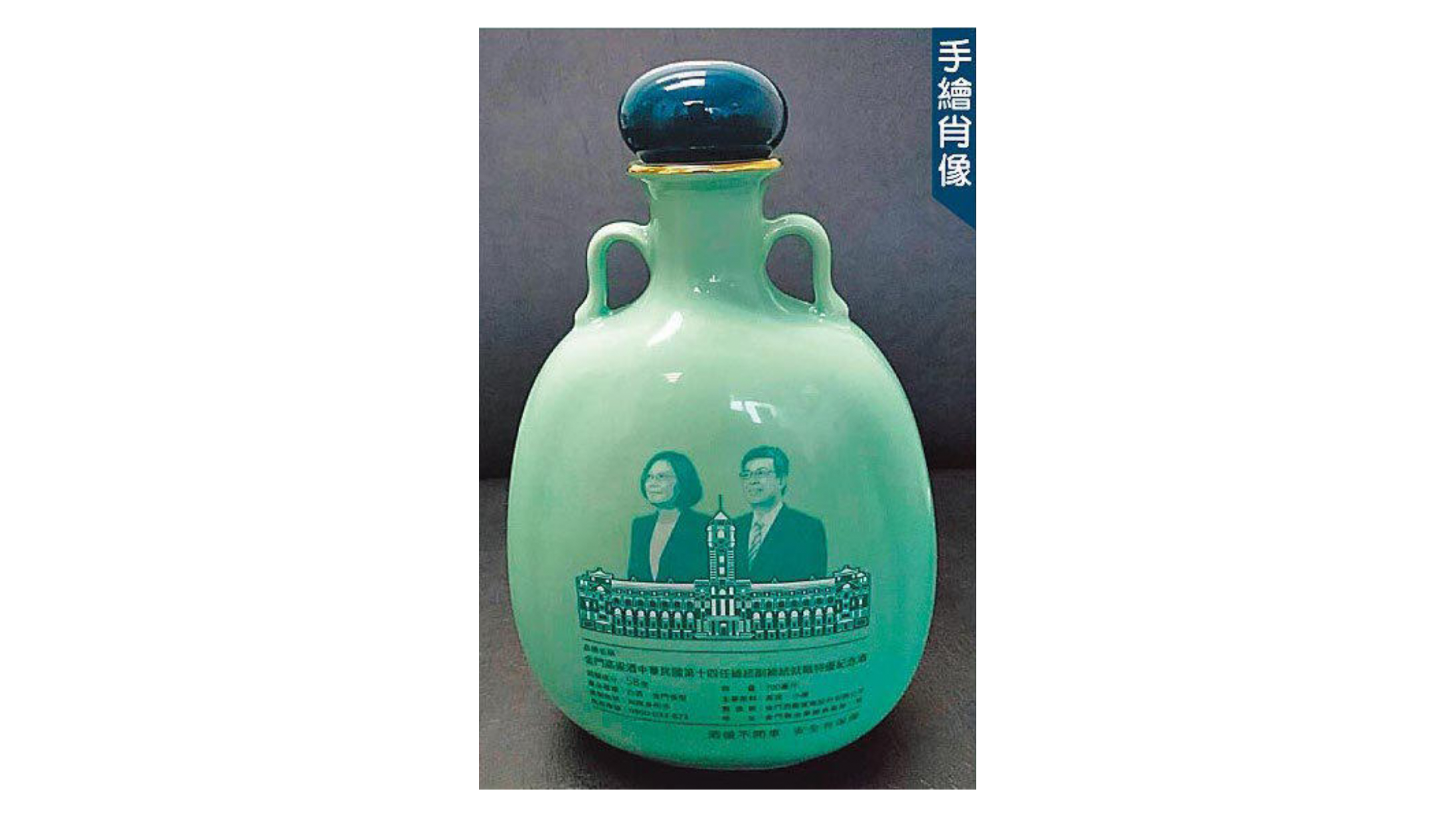

But back to the story of kaoliang. In many ways, kaoliang is Taiwan’s “official alcohol.” Whenever a new president takes power, for example, a commemorative kaoliang is produced by the government–usually looking rather tacky, as is generally the case with most forms of kaoliang packaging. Political leaders from Taiwan customarily bring kaoliang with them as gifts on diplomatic occasions. When then-president Ma Ying-Jeou visited China to meet with Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2015 as part of his efforts to bring Taiwan closer to China politically, Ma brought high-class kaoliang with him as a gift for Xi, for them to drink at the official state banquet held after their meeting, while Xi brought Chinese maotai. After the meeting, Ma made the comment, “Apparently neither of us is a good drinker.”

Taiwanese kaoliang is produced far from the Taiwanese mainland on Kinmen, making its iconic status as the national spirit vaguely questionable. One of the most popular kaoliang brands in Taiwan is Kinmen Kaoliang Liquor, which has its origins in the state-run monopoly on alcohol production during the authoritarian period under the Kuomintang. Because Kinmen was a battlefield, seeing constant shelling from China and requiring constant supplies from the Taiwanese mainland, the military garrison on Kinmen came up with the idea of having local farmers barter sorghum wine for rice.

Because of China’s tendentious claims over Taiwan, I have heard that Chinese imports of kaoliang have attempted to cover over references on kaoliang labels to “Taiwan” or the “Republic of China,” Taiwan’s legal name, with “Taiwan, Province of China.” The response was to carve the labels directly into the glass itself, so they can’t be replaced or covered over. Kaoliang also plays a role in elements of Taiwanese spiritual life. Spiritual mediums sometimes drink kaoliang to induce spiritual trances. This is particularly true of mediums for Ji Gong (濟公), the drunken Buddhist monk deity popular in Taiwan, who used his supernatural powers to fight evil. Sometimes worshippers will leave bottles of kaoliang at Ji Gong temples in order for him to charge them up with supernatural power before taking them back.

Here’s a video of a drunken Ji Gong, having drunk too much kaoliang:

With a burgeoning cocktail culture in Taiwan in recent years, I’ve seen many attempts to create cocktails out of kaoliang. The idea would be to create cocktails representative of Taiwan, in line with the search for symbols of Taiwanese identity that one sees among many young people. None I have tried has ever been really successful. However, funnily enough, I am told a drink exists in Kinmen called Mao Zedong Bubble Tea, which is made from mixing bubble tea—Taiwan’s so-called “national soft drink,” often called just “boba” in the States, “boba” referring to the chewy tapioca balls in bubble tea—with kaoliang. Why “Mao Zedong” Bubble Tea when, say, Chiang Kai-Shek would probably be more appropriate, given Kinmen’s military history? I don’t know. But I plan to try it, and report back here shortly.