According to legend the mu‘allaqāt, the Hanging Poems, written in the sixth and early seventh centuries CE, were thought so fine that they were hung either on or in the Kaaba in Mecca, which was already a site of worship in pre-Islamic times. The very first of the seven to ten Hanging Poems was written by Imru al-Qays, whose father was a king from the Kindah tribe. Although the desert environment was a harsh one, Imru al-Qays grew up in relative luxury. His scandalous dalliances with women and his famed drinking parties created a rift with his father, who exiled him from the tribe. The poet began a wandering life, which took on renewed intensity after his father was killed by a rival tribe, with Imru al-Qays vowing to seek revenge.

All the Hanging Poems, including that of Imru al-Qays, feature strong, regular meter and consistent rhyme. There are two primary choices available to the translator here. The first would be to attempt to mirror the source text by imposing a similar strong meter on the English, and perhaps a rhyme scheme as well. The second option would be a free verse translation. I’ve chosen the latter because it seems more in line with modern English poetics, and because part of the functionality of the meter and rhyme of the Arabic—that of aiding in the memorization of these texts, which were likely passed down orally for well over a century before any of them were written down—is no longer applicable. This choice also lines up with my general goal, which is not a scholarly line-for-line rendition, but rather a poetic translation that renders these dense texts accessible to the modern reader.

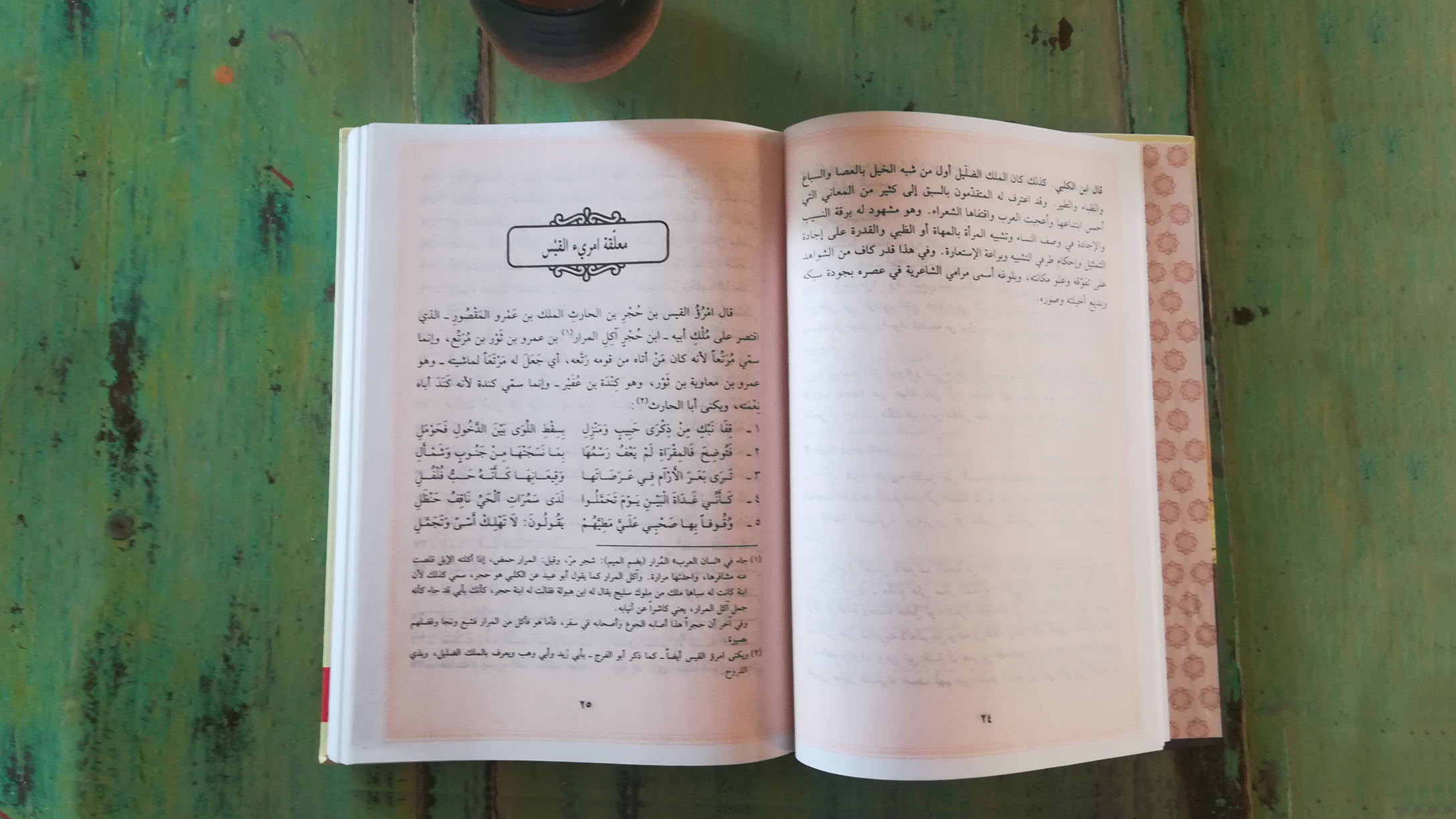

The following short section from Imru al-Qays’ Hanging Poem, with its tone of despair, was likely composed after the death of the poet’s father:

Night

Night casts its veils on me

time and again

like waves of the sea—

a host of cares

to try me.

As it stretches its spine,

as it straightens its hind legs

to rise like a camel,

I cry out:

“Endless night,

won’t you clear off

with the coming dawn?”

But dawn brings no respite.

What a night you are—relentless,

as if the stars were pegged to Mount Yathbul

with the strongest of ropes.

As if cords of flax bound the Seven Sisters

to lofty stables of solid stone.

Rather than trying to mirror all the specific musical qualities of the Arabic, I’ve sought to capture the poetic feel of the Arabic through a modern musicality that uses internal rhyme (spine/hind) assonance (hind, rise, I), consonance (Seven Sisters, stables, solid stone), and other effects, including the occasional use of strong and weak end rhyme (me/sea and night/respite). Poetry, to me, is a whole set of effects—much more than just meaning—and it is virtually impossible to mirror all of those in a translation. I prefer to think more in terms of compensation. Yes, I’m losing the strong rhythm and end rhymes, for example, but I’m compensating for that loss in other ways, in order to transform this classical text into an effective English poem that gives a truer sense of the original Arabic.

A few verses of this poem merit particular attention. “As it stretches its spine, / as it straightens its hind legs /to rise like a camel.…” A more literal translation of the Arabic would be: “As it stretches its spine, lifting its chest and buttocks.” It’s critical for the translator not to focus exclusively on the meaning of individual words. While a very literal translation would be “faithful”to the meaning of the words, it would also be unintelligible for most readers of English. To a pre-Islamic audience, the image here would have been crystal clear: It is that of a camel, since camels roll and stretch their spines before standing up hind legs first—as opposed to horses, for example, which stand up front legs first. But even describing the motions more clearly is inadequate here, due to the gulf that separates the pre-Islamic Arab audience from modern English-language readers; this landscape is very foreign to modern readers. I have therefore added the verse “to rise like a camel”—otherwise, the crux of the image is utterly lost in English. Here, the overall image is at least as important as the individual words that comprise it. Making such choices—the choices of which aspects of the source text are the most critical ones to convey—is one of the translator’s primary tasks.

Legend has it that Imru al-Qays waged war against the tribe that murdered his father and avenged his death, yet he was never able to restore his father’s realm. He remained an exile, a vagabond, a king without a kingdom. But he left his poetry behind for us—a final gift to the world.

Kareem James Abu-Zeid