Taiwan’s government remains unrecognized by most of the world’s countries owing to pressure from Beijing, which has sought to absorb the island for decades. But for now the Taiwan government is independent of China in all respects, despite this powerful geopolitical tension.

The framework of “One Country, Two Systems,” in which Hong Kong will nominally retain its own system of government until 2047, half a century after Hong Kong was returned to Chinese control by the British, was originally formulated to draw Taiwan back into China’s fold. So Taiwan has long viewed Hong Kong’s fate as a potential prequel to its own fate, if it, too, were to be annexed by China.

China continues to try and lure Taiwan in on this same basis: In a recent speech, Chinese president Xi Jinping promised that if Taiwan unified with China, it would be allowed to preserve its political freedoms under the framework of “One Country, Two Systems.” The surprisingly pro-China results of Taiwan’s recent elections show clearly that many in Taiwan have yet to realize how hollow such promises have proved in Hong Kong.

By now it’s plain that the deterioration of Hong Kong’s democratic freedoms began soon after the 1997 handover. Two decades later, Hong Kong is a place where the government can prevent you from running for office, dissolve political parties, remove lawmakers at will (even if they win office), jail political critics for extended periods, and employ gangsters to physically assault critics of Beijing, all with impunity. To top it off, though Hong Kong was hardly an egalitarian society under the British, inequality has increased even more under Chinese control.

Taiwan can scarcely help seeing in Hong Kong the reflection of itself “in a glass darkly.”

During the protests leading up to the Taiwanese Sunflower Movement in March 2014, a slogan frequently seen on signs read “Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan” (今日香港,明日台灣), implying that Hong Kong’s fate would befall Taiwan under the terms of a proposed trade deal with China, which the protests succeeded in preventing.

I also sometimes saw the sign’s inverse, reading “Today Taiwan, Tomorrow Hong Kong,” (今日台灣,明日香港), particularly after the attempted storming of the Executive Yuan, Taiwan’s executive branch of government, resulted in a wave of police violence against student demonstrators, a group including myself. This sign suggested that open violence would eventually come to Hong Kong because of Chinese pressures, just as it had come to Taiwan.

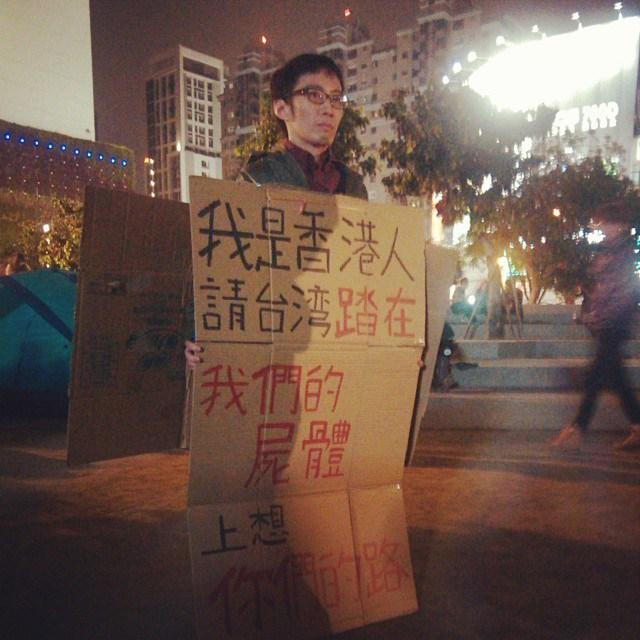

A number of participants in the Sunflower Movement were students from Hong Kong studying in Taiwan. There were even some Chinese students studying in Taiwan who participated in the movement. In one memorable incident, a man from Hong Kong arrived at the occupation site holding a sign that said “I am a Hong Konger. Please step on Hong Kong’s corpse to advance forward, Taiwan” (我是香港人,請台灣踏在我們的屍體上,想你們的路).

In Taiwan, the Kuomintang and other right-wing political forces favor unification with China, generally because they are social and economic elites who seek to to retain or amplify their elite status under Chinese rule. Even so, there is no direct pressure from China in Taiwan’s politics, in sharp contrast with the political situation in Hong Kong. China directly controls the Hong Kong government, while the Kuomintang still has to fight its battles out in elections.

Hong Kongers themselves were caught by surprise when organized protests broke out in their own country in the form of the Umbrella Movement, which took place only a few months after the Sunflower Movement protests. At the time, friends from Hong Kong would tell me that residents of Hong Kong were simply too indifferent to politics, too concerned with their jobs and making money to organize a movement like ours. (Truth to tell, the same had been said of Taiwan before the outbreak of the Sunflower Movement.)

Five years after both movements, now what?

Some read the results of local elections in Taiwan, which took place in November, as proof that the gains of the Sunflower Movement have been undone. While political freedoms in Hong Kong were on the decline before the outbreak of the Umbrella Movement, punitive actions from Beijing, such as the outright prevention of certain candidates from running for office, did not take place until after the protests.

The Umbrella Movement benefited from international media coverage in a way Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement did not. Though Taiwan is many times larger than Hong Kong in terms of size and population, Taiwan is less recognizable in international affairs. Most significantly, China seems to have created its own worst enemy: Hong Kong has been Asia’s media hub since 1949, when foreign journalists from the mainland were forced to relocate there.

But foreign journalists are increasingly facing expulsion from Hong Kong as well, as observed in the case of Financial Times news editor Victor Mallet, who was denied a visa renewal last October—and then refused entrance to Hong Kong even as a visitor. Where will journalists banned from Hong Kong go next—perhaps Taiwan? Perhaps presciently, in view of the Mallet affair, Reporters without Borders opened its Asia offices in Taiwan in April 2017, anticipating the continued deterioration of media freedoms in Hong Kong.

Links between Taiwanese activists and Hong Kong activists have always been strong. Many of the key leadership figures of the Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement knew each other personally well before any of them became famous.

I sometimes think of the activist world as being like the jianghu of Chinese-language martial arts novels. The term means “rivers and lakes,” and refers to the sphere of itinerant martial artists who are forces for justice, as for example in the wuxia novels of Hong Kong writers such as Louis Cha. The concept is highly influential on film, literature and pop culture in Taiwan and elsewhere in the Chinese-speaking world.

It’s truly frightening that the Chinese government is completely aware of the longstanding links between activists as well, even down to subtle connections which largely escape the public eye. It will sometimes draw on personal connections to attempt to intimidate high-profile activists through threats to their acquaintances. Given their sensitivity and privacy, these stories are not reported on. And, well, I can’t say anything publicly either, but sometimes I feel really glad that I’m just small fry, comparatively speaking, and that, as a journalist/commentator, I am to some degree shielded from more direct threats. Sometimes I really don’t understand how some of my friends who are high-profile activists deal with these kinds of pressures on a day-to-day basis. The jianghu can be a small place sometimes.

From outside Hong Kong there’s very little I can do, and that scares me. I feel a similar sense of powerlessness with regard to Xinjiang where, at best, sometimes I can write about what is taking place there. Compared to Xinjiang, information on events in Hong Kong is far more readily available.

At least it’s a way of caring. And it’s good to see that people in Hong Kong care about Taiwan, too. An article about Taiwan entitled “The Island the Left Neglected,” published in Dissent. Surprisingly, few noticed it was written by a Hong Konger, Jeffrey C.H. Ngo, an activist historian affiliated with Demosisto, the post-Umbrella Movement political party. This article itself was a form of solidarity.

“Solidarity” is a beautiful word, but what can you do from the outside to help?

It is becoming increasingly difficult to conduct direct meetings between residents of Taiwan and Hong Kong. While Hong Kongers can still come to Taiwan, many high-profile Taiwanese activists and academics are blocked from entering Hong Kong. Those who manage it seem to get in through mere oversight. After one well-known activist went there to give a talk recently, some Hong Kong activists quipped to her, “Welcome to Hong Kong! It’s your first time here. It might also be your last time here.” It seems very possible that Hong Kong activists, too, may soon be denied permission to leave.

The few statements of solidarity we can make, as with post-Sunflower Movement political parties in Taiwan such as the New Power Party or the Radical Party, often feel insubstantial to me. People like to throw around pretty phrases about the power of words, of expression—the power of the political dissident, usually in the form of an intellectual, writer, philosopher, artist, musician, or some variant thereof. But what purpose does expression serve? It’s like trying to write on water. It doesn’t last.

When I tell that to friends from Hong Kong, they sometimes mention, again, that at least it’s a way of caring. Which always surprises me. What good can caring do? Still, maybe clearer possibilities for some more direct way of cooperation will emerge, down the line. It’s at least a start. If we didn’t care about these places, we wouldn’t be willing to take such risks for them either. It’s a start, even it remains to be seen what can go beyond offering expressions of solidarity back and forth.